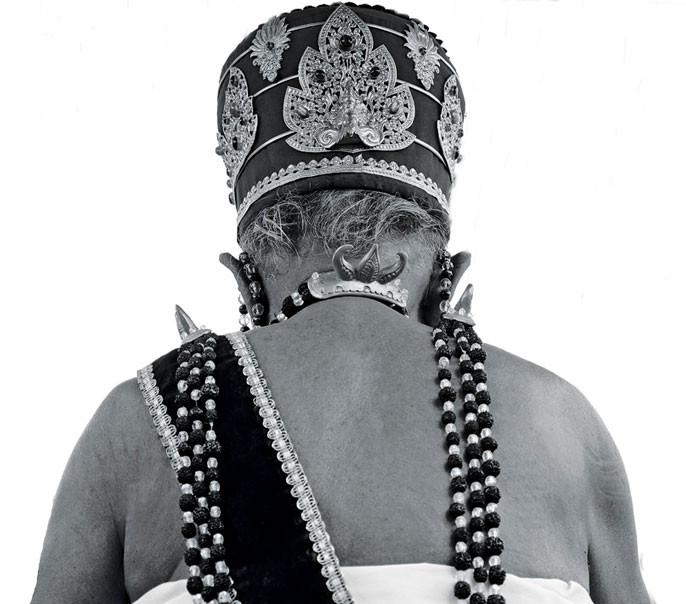

The faithful were now all gone, and all that remained was only scattered on the ground, the remains of the offerings: torn coconut leaves and trampled flowers; the air was moist and filled with the scent of burned-out incense mixed with the strong odor of the drying earth. It was all over now and, his job done, the old wrinkled man, standing silently at the inner gate, a monstruousBhoma head overlooking him, was pondering in silence. His eyes passing across the two rows of altars, where the gods were now resting: After his death, who would take over his job as temple priest? Who would decorate the altars, clean the effigies, bathe and pamper them, and call the gods to alight on them? Who would present them with the offerings of the people and sprinkle the holy water. Who would look after the altars, these “puppet houses” of the gods, and wrap them with the white and yellow colors of Siwa. In short, who would be the next temple priest and see to the rites of the gods?

Mangku Gede, the temple priest (mangku) of the Natar Sari temple of Abiangombal had reasons to worry. He had no son, no male heir to take over the custody of the temple after his death. His only child was a daughter, Rasmini. As his only child, she would have to find a man to marry, who, by taking her hand also accepts to move into her father’s clan and take over all her father’s duties. When found, the husband, in this nyentanaunion, would have to become the priest of the Natar Sari temple.

Rasmini did indeed find such a man. Being a faithful daughter, she was entrusted to fetch the water from a little spring two hundred meters from her father’s backyard, down by the deep river gorge. Several times a day, she would be seen, always smiling, patiently climbing up and down the slippery path down to the river bed, with her pails of water and her towel and soap. She collected her water and also bathed from a spout on the huge flank of sandstone, which occupied the lower part of the gorge. Downstream, one could hear the thumping of hammers and the grating saws as workers were cutting the stone into construction blocks and bricks.

Rasmini caught the eye of one of the quarry workers. The first time she saw him, hammering at the stone, he winked, and she was soon in love. Thereafter, she would go more often to the spring, bathe longer and offer to his eyes the gleam of her dripping body.

There was a hitch, though: he was Javanese, a Moslem, who had come with other immigrant coolies from Java. There was no precedent to the situation. No Moslem Javanese had ever nyentana (entered a girl’s family as heir) in a priest’s family. Mangku Gede objected indeed; he approached a cousin, then a neighbor; but Rasmini would not have any of these “good” Balinese. She was hooked on her man from Java. She was in love.

Things were not easier on Amin’s side, the fellow from Java. He was circumcised, fasted the first three days of the holy month and would even now and then show his nose at the mosque. He also vaguely knew that, as a Balinese, Rasmini worshipped gods in numbers and was not, therefore, a woman of the Books. Thus, he wanted her to become Moslem and go back to live with him in Java. But Mangku Gede was adamant. He would accept Amin as a son-in-law, but under the condition that he had to nyentana and the new responsibilities of a mangku (temple priest).

Luckily, Amin had not forgotten that, although a Moslem, he was a Javanese too, and he knew an “old man”, a dukun (medium), well versed in the secret books of Java, the primbons; he consulted the dukun for advice.

“My son,” the old man told him two days later, in the heat of his small wooden shack, “you wonder about your sins if you become Balinese and a priest. But aren’t Java and Bali the same, and wasn’t it written, in the book of Sabdapalon, the adviser to the king of Majapahit – the last Hindu-Javanese empire – that the days of old would come back alive again after five centuries. These times might have come, my son, so go back to Bali, marry the girl and become a temple priest.”

An ultimate and naive witness to the slow pace of historical change, Amin then went back to Bali and his love. He is now married, happy and is learning the trade: he will be he next priest of the temple of Natar Sari.

Mangku Gede could smile and prepare himself to rejoin his ancestors, whose souls are waiting on high above the Balinese Mountains.

Text By Jean Couteau Photo By Ayu Sekar