Mysterious images of a distant exotic island of the East Indies began circulating in Europe in 1920. During an era when Europe was reeling from the horrors of World War I and the fear of a communist revolution, the photos published in two volumes, ‘Bali’, caused a minor sensation. They struck a chord with disillusioned Europeans after millions of lives were destroyed and the confidence in western culture was severely weakened.

People were yearning for fresh experiences, escapes to different cultures, and a tropical paradise. Soon after, adventurous travellers journeyed to Bali and began documenting a beautiful and seductive world. The text in books romanticised the Balinese as living in harmony with one another, nature, the universe and the divine through art and agriculture. The imagery and text projected the idea of a utopia – Bali, the island paradise.

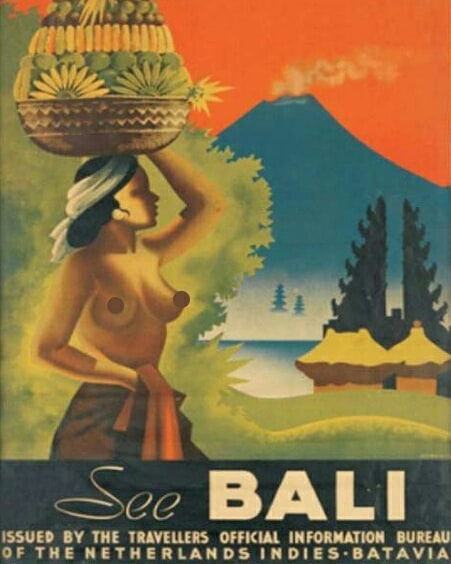

A turnaround in western perceptions of Bali occurred. From the initial belief held by foreigners during the 1800s who bypassed the island of “Savage Bali”, a dangerous place, always at risk from war, plague, famine, and volcanic eruptions. Then came the notion of “Female Bali” (the island of bare-breasted smiling women), which then evolved into “Cultured Bali” (where everyone is an artist).

First Tastes of Tourism

The aftermath of the extraordinary Puputan events during the early stages of the Dutch colonisation of south Bali in 1906 in Denpasar and 1908 in Klungkung became highly significant. The circumstances in which the royal families and their courts, rather than surrender to the invading forces, committed ritual suicide were instrumental in changing attitudes.

A strategy developed, emphasised by civil servants who believed that the Netherlands owed a “debt of honour” to the colony to help ease their conscience. This strategy gained positive responses from western European nations that reacted negatively to the Puputans. The idea of “preserving” Balinese culture, along with developing tourism to help restore the colonialist’s sense of pride, was born.

In 1914 the first tourists arrived in North Bali aboard a Dutch liner from Java. The numbers increased to 100 people per month by 1930 and 250 per month in the early 1940s. A tourism industry infrastructure quickly evolved. The image-making process of tourism promotion was often selective and concocted, creating ideas about what Bali represented as a marketing ploy.

“Images of bare-breasted women, dancing girls and witches dominated the male eccentric essence of what represented culture.” states Adrian Vickers in ‘Bali: A Paradise Created’.

Source: Tropenmuseum

Outsiders’ perceptions of Bali, its exciting new culture and tropical enchantments brought about a revolution in image consciousness during an era of abrupt and rapid change in the early decades of the 20th-century Western world. The idea of Bali as a tropical paradise took hold.

The first president of Indonesia, Sukarno used images of the island to integrate Bali into the modern Indonesian state. Symbols of beauty, peace and harmony represented the new nation onto the international geopolitical stage during the 1950s. Balinese culture was elevated to new heights and status within Indonesia. The modernisation of Balinese paintings in the late 1920s for the new tourist market also impacted the perception of Bali as a beautiful, tranquil tropical paradise rich in culture and mythology. President Suharto’s cultural tourism program in the 1970s perpetuated these ideals within the international marketing during an new era of tourism.

A new phenomenon of image-making occurred in the 1980s with the development of mass tourism; resort tourism and later the luxury villa experience altered the presentation of imagery from cultural to lifestyle activities. The 21st-century digital information age had a dramatic impact on how images of Bali were consumed. Experiential tourism shifted the focus to the human experience while the cultural icons played a secondary role.

Tourism Today

We are living in the era of pop-culture selfie-mania. Technology and smartphones have democratised visual self-expression, with social media and imaging apps allowing us to constantly “curate” our digital presence, enhancing our obsession with our perfect self. Recent tourism trends are defined by the upwardly mobile younger generations flocking to Bali seeking lifestyles experiences and a new place to call home. Social media influencers promote the must-visit selfie locations. Increasing imagery of pleasure and leisure suggests a shift away from the cultural pull that Bali was originally known for. While the potential to attract awareness and visitors, boosting the local economy is real, the increasing decadence of the imagery brings into question the value that social media influencers represent.

The image-making of the past century reveals patterns of ongoing exploitation of Bali. While the Indonesians and Balinese are active participants due to livelihoods derived from tourism, neo-colonialism appears to be the norm. Many foreigners are attracted to live in Bali because of the cheaper cost of living and the tolerance that the culture promotes. Many appear, however, to neglect the tangible value Bali offers, and seemingly wish to take advantage of the many things the island offers. Bali’s cultural practices and philosophical wisdoms, however, bring sustenance to the mind, body and soul. This becomes especially relevant to humanity during the pandemic and the increasing corruption of corporate governments worldwide.

Contemporary image-making endorsed by society does not represent a heightened state of illuminated human experience expressing principles of the universal law of abundance. It describes a species absorbed in self-gratification compelled by the individual notion that the outward appearance of perfection mirrors what is within. This self-obsession reveals our ongoing identity crisis and psychosis caused by our disconnection with nature and spirit that has ravaged the modern age.

What is to become of Bali when the door to international visitors reopens? Certainly, local and foreign tourism operators and those who derive their livelihoods from tourism will rejoice. On the other hand, traffic gridlocks, ongoing environmental vandalism, neo-colonialism, exploitive behaviour and hedonism will continue as the norm. How do we reconcile with our lack of vision for the Island of the Gods? Who must start to take responsibility, and when?