You may have seen, while driving, a white-dressed priest busy uttering some mantra on the side of the road, impervious to traffic. “Crazy,” you might have thought. And you were wrong, because the priest was there with a precise function: to bring meaning and balance to the “order of things”. What you saw was a “ngulapin” ceremony, which aims at calling back (ngulapin means “call”) a soul sle?

Let us take an example. While riding his Honda bike on the way back from a temple ceremony in Singaraja, Ketut Asmarajaya missed a curve and fell. He lost consciousness. Taken to the hospital, he woke up feeling “strange” and dazed. But it was only the beginning. The following night, he says he was visited by a big, hairy monster, the duwe (spirit) who owned the place where he fell. This duwe kept his soul prisoner. So, naturally, there was no hesitation: Ketut had to put back things into order.

The Balinese believe that when a person has an accident, or a serious mishap in which the person suffers from a lapse of consciousness or displays abnormal behaviour, a rite intended to bring the soul back to normality must be carried out. The accident is believed to have “dislodged” the soul . Unless the ngulapin rite is performed, the person will be unable to forget the accident. He or she will experience a long-lasting trauma or mental distress. If the accident causes death, the same rule applies, lest the lost soul should roam about the village and cause illnesses and incidents.

To understand what is taking place, one must first accept that a human “soul” is not in Bali what it is in the West. A soul is not born; rather a soul reincarnates. It is an ancestor who “comes down” from the cosmic void in a new human garb, after it has been cleansed in purgatory (tegal penyangsaran). Yet, it does not reincarnate alone, but together with a set of astral “forces”, which are called its Nyama Pat (also called Kanda Pat, Catur Sanak), its four “brothers”. Corresponding to the four directions of the compass, these “brothers” establish the link between the self and the macrocosmos. A proper balance must be maintained between the two, lest accidents, illnesses, mental disorders etc, occur. People explain such disruption by saying that one or several of their “four brothers” has jumped out (melecat) from the soul’s companionship and does not protect it anymore. These “four brothers” are then kept prisoner in the invisible “niskala” world. It can be released, but under certain conditions only. It has to be “exchanged” against an offering: a dark chicken. Why dark? Because it is the colour of the god Wisnu, the provider of order in the Middle World of humans.

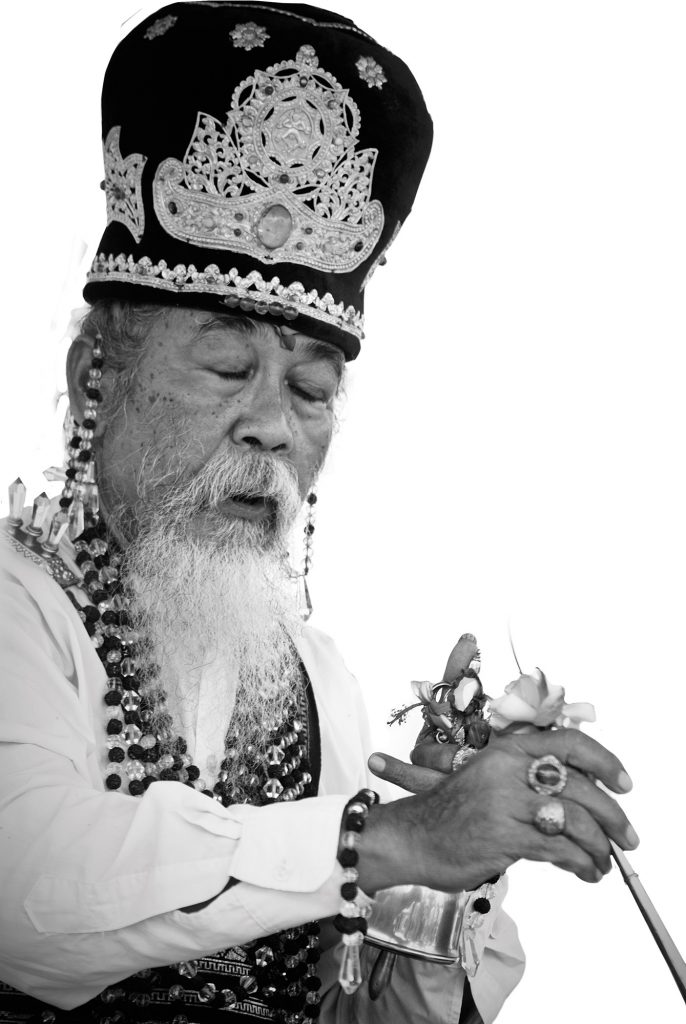

There are many types of ngulapin rites, according to the importance of the disturbance, and the status of the person(s) involved. Sometimes the rite is officiated by an ordinary temple priest, a pemangku; at other times by a shaman-priest, balian sesonteng; or else by a pedanda, a high priest. The levels that occur are: nista for the inferior; madia, the medium; or utama, the superior. Bebanten nista, or offerings of the inferior type – which are the most commonly used – have to be offered within three days of the event. If the rite is performed too late, the soul could have already wandered far away and, therefore, be hard to “catch and bring back.” Yet, in the case of a longer period between the event and the offering, a second type of banten, which is called bebanten madia, should be used. When the case is complicated or the sufferer of high status, a Pedanda priest will be preferred. He is said to possess higher spiritual knowledge and ability, owing to his caste superiority and his knowledge of the most powerful mantras. The officiating priest is normally assisted by a woman, in most cases his wife.

How much does a ngulapin rite cost? A few hundred thousand rupiah, to which have to be added the sesari. Sesari is the maker’s fee, the amount of which depends largely on the wealth and the good will of the customer. Ordinary banten itself consists of flowers, young palm-leaves, fruits and cakes arranged decoratively on bamboo trays.

The ordinary nista offerings are made at a street corner, whereas the ngulapin rite of medium level is performed at the main village crossroad, the perempatan agung. This crossroad is the preferred roaming place of the demonic dwellers of the village, the bhutakalas, so it is where they can be most easily placated, by caru offering on the ground. Another set of offerings is addressed not to demons, but to a god, Sang Hyang Catus Pata, the Lord of the Four Directions. They are accordingly put not on the ground, but on a small platform. The prayers are said to have been bequeathed by the mythical priest of Bali, Sang Kulputih.

During the performance of the ceremony, a black chicken is set free. It literally “buys back” (nebut) the lost “brother”. The priest then touches the person’s chest three times with a device called a sanggah-urip (the shrine of life), while his hand gesticulates as if trying “to catch” the wandering soul and to “put it back” into the person’s body. The participants say that they feel a strange sensation, as a sign that the soul is passing by. The sanggah-urip will then be placed under the patient’s head for three days, to ensure that the soul is really resettled. A patient, upon his arrival at his or her home, is given another short rite in front of the entrance.

If the person dies, the function of the rite is not to “resettle” the soul, but to keep it under control, and thus, prevent it from wreaking havoc around a place. In such a case, someone collects some earth from the place where the person died, usually in front of the Padmasana altar (dedicated to the Supreme God) and takes it to the cremation ground.

The Balinese never fail to keep things in their proper place. Even souls, despite their subtlety, should be subjugated. After all, there is a right place for everything.