For most ordinary people, which is in the world out there, it goes without saying that there are 24 hours a day and sixty minutes in an hour. To them, thus, time is a tool, repetitive and familiar.

However, that is a far cry from how traditional Balinese circles perceive the same period of time. Days pass of course, but in more “meaningful” ways: not only do the calendar days have an individual value —auspicious or inauspicious— and there are charts to read it, but there are divisions within a single day, that are no less important to know if one wants to lead one’s life securely, out of reach of the niskala (intangible) forces and other bhuta demons on the prowl out there. So readers, get ready to think differently.

Light, Darkness and the Deep Scare

The main division of day in Bali, like everywhere, is that between daytime (galang/lemah) and nighttime (peteng/wengi). The day here starts with the rising of the sun, which is also the coming of life. Only strange people, Westerners like myself for example, would have the day starting at midnight, in the depth of darkness, which is the time of fear, as we shall explain below.

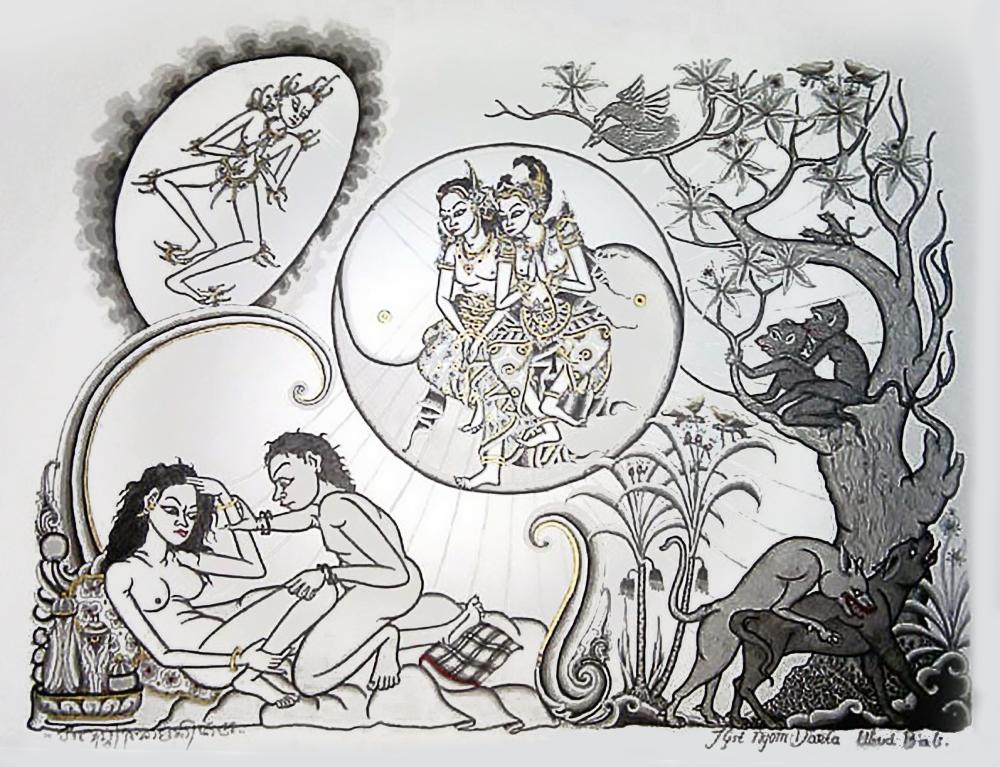

In this division between day and night lies a stark contrast between light and dark, which helps to define not only the notion of the day but also the months, on account of the combination of the sunlight and the moonlight. In Balinese lore, the godly couple known as Candraditya (the Moon Goddess and Sun God), an emanation of Siwa, rules over the light, whereas the frightful goddess Durga, Siwa’s consort Uma in her demonic form, rules over the dark. The sun is masculine, as the God Surya –also called Aditya or Baskara— is taken across the world on his chariot as light comes and fades. His partner, the moon, is feminine, named Candra or Ratih. The latter is portrayed as weaving faithfully for her husband the god of love Smara, and is also shown pursued by the destructive lord of time, Batara Kala, who eats her at intervals – hence the phases of the moon.

All these classifications —day and night, light and darkness, Siwa and Durga, sun and moon, Smara and Ratih, masculine and feminine— are seen by the Balinese as overlapping manifestations of the Rwa Bhineda principle, the ultimate dialectics of complementary opposites that create, and are, at once the working on the cosmos, God and the gods.

The Balinese day consists of transitions called sandi kala (from sandi = joint and kala= time), which are the moments when a cosmic change is taking place in relation to the earth on one side, and the presence of sun and moon on the other side. There are four main transition moments, not including moonrise and moonset: sunrise (endag ai); noon (tengai tepet, tajeg Surya; jejeg matanaine, or nyerepetan), sunset (sandi kala, sandi kaon or engseb matanai) and high moon (nyerepetan bulan).

These sandi kala are important. Unless we are particularly strong, we are not advised to bathe or to take a walk during these “joint” or transitional periods. Nasty kala demons are out and they might enter you through your feet if your condition is weak. Thus you will be in for bad times, even if you are not aware of it.

Danger increases at the coming of sunset, as the world prepares itself for darkness. Villagers will say that “leyak” masters, or Balinese witches and sorcerers, start readying their evil tricks as soon as they have fed the pigs, which is just before sunset. The later darkness advances, the more numerous and stronger are the forces of evil.

Not all is bleak in the dark though. The darkness of night is also chosen for positive meditative fasting, when you are facing the darkest forces around. Then we have the literal light of the darkness, the moon, where Ratih herself comes under the spell of love, Smara. Yes, when moonlight shines down upon the earth is the ideal time for lovemaking, but do so only after making the right offerings as you will be duplicating the lovemaking of Ratih and Smara… and indeed do so only after the children are sound asleep (asirepan rare).

The noon of the moon (nyerepetan bulan), when it is at its highest point in the sky, is a moment to be wary of however. This is when the leyak witches are out frolicking obscenely, admiring their grotesque reflections in the pools under the moonlight. It is a high time for the blackest of magic, when tombs are open and rotting cadavers exhumed to be eaten or presented to Durga.

It is not that easy to become a leyak, though. There are complex ritual procedures: you have first to request “authorisation” from the gods of your family temple –from Kala the terrible and Batara Guru the teacher god. Once this is done, you have to repeat the procedure in front of Durga in the temple of the dead (Pura Dalem) during the “dead” of the night. Not that easy, with all the forces you wake up. Just in case, if anything happens, you are advised to take along some rice wrapped in a banana leaf and eat it: you will be protected by Sri, the goddess of rice, who dwells in the rice consume.

At night, if you are with a lover, the safest is to stay with him or her, until the second rooster’s crow (kruyuk pang pindo), in the morning, or when the rooster comes down (tuun siap) to herald the day, when it becomes safer outside. For the same reason, traditionally, when beyond the depth of the night, dances are part of the cosmic forces at work and they have to last the whole night. It becomes safer when morning approaches. Then Durga, such as played in the Calonarang story, calls back to all her “disciples” (sisia) and only then do they return back to their niskala (intangible) abode. The godly lovers interrupt their game, as do humans and demons: the ground is becoming clear (agalang tanah) and even the coins are recognisable (ngenah pipis akepeng). Sang Hyang Baskara, the sun god, is profiling himself on the horizon.

Day Time Units: No Hours, but Dauh

The Balinese days, beginning with the sunrise, are not divided into hours, but into dauh, sometimes called dawuh in the old Kawi language, which means “fall” and seems to refer to the striking of the hours in ancient times (Zoetmulder, 1963, P.242), possibly to command people to village or royal corvée (dedauhan). The dauh is not a regular time unit. It changes from season to season according to the relative length of the day and the night. To make things more complicated, there are several types of dauh. There is a system of five “dauh”, called Panca Dauh, meaning that the days and the nights are each divided into five units of around 2 hours and 20 minutes, adjusting for 10 minutes or so depending on the season. There is also a system of eight dauh, called Asta Dauh, with eight units of more or less 1 and a half hours each. This dauh system is the most commonly used.

What is the purpose of these dauh systems? To organise one’s daytime life according to propitious or unpropitious time: for example when to begin a ceremony or planting rice. There are complex Wariga charts for the purpose, based on computations using the “pangider-ider” Rose of the Winds, where the moments of time (dauh, days, months etc.) have a different value according to their compass position.

The dauh system looks “primitive”, but it is sufficient, in most cases to know when one should leave for school or get ready to dance. One should not rely on it, however, for business appointments.

How did people tell time

Traditionally, people would tell time using sun-dial-like tools, like pillars or verandahs to observe the sun shadow. When the shadow is tilted to the West (seng or singit kauh), they know it is “dauh telu” or dauh three. At tengai tepet (noon), the sun is directly overhead and the shadow disappears. It is time to rest and eat. But just after, when the sun starts creeping to the East (seng kangin), comes the time when cremation processions can start. When the sun “grows old” (lingsiran) it will be time to bathe, give pigs some food and wait for the sun to set, at dauh 8 (aroung 5-6) when all activities should stop, since demons and witches would soon be on the prowl.

What about “minute” time. The Balinese do not seem to know the short partition of time derived from earlier Indianised times. They still practice primitive time counting, like using pierced coconuts filled with water, but these are used on special occasions, like cockfighting.

The Balinese have qualitative ways, however, to tell the “shortness” of time: a “moment” is translated by the time needed to chew the betel (apakpakan base); a “while” by the “wink of an eye” (akejep). However, matters get complicated when someone tells you to “wait for a barong’s wink” (akejepan barong), since the barong wears a wooden mask with eyes that don’t move. In other words, in Bali, be ready to wait!