Each year, millions of globetrotters descend upon the island of Bali seeking a taste of the tropical paradise, from exploring the riches of its pristine beaches to trekking the majestic landscapes, Bali has no limitations when it comes to the plethora of experiences that visitors can discover. However, Bali is first and foremost known for its rich history and unique culture that goes back centuries, and there is one destination in particular that is most well-known for both of these: Ubud.

Recognised as the cultural and spiritual heart of Bali, Ubud’s own history is in one way or another the birth of the island’s history itself. To explore Ubud’s complex origins, we must take into consideration its past myths and legends, which are often intertwined with its historical facts.

The Mythical Origins of the Island

The earliest recording of Ubud’s history is believed to have gone back to the 8th century with the arrival of the first Hindus, led by a holy man named Rsi Markandaya. The nomadic Indian priest first arrived in Java, before he embarked on a journey towards the east with some 200 followers until he reached the eastern tip of Java. There, from the slopes of Mount Raung, was the first time he laid his eyes on the island of Bali, an unexplored wilderness beyond the straits.

Gathering a group of 800 followers, Rsi Markandaya finally crossed over to Bali, no more than three kilometres away, and made his way to the towering mountain on the easternmost edge called To Langkir, now known as Mount Agung. However, their expedition was ravaged by plague and disaster. This led the priest to retreat to Mount Raung, where he meditated for 35 days and nights. It is believed that during his meditation, a heavenly voice spoke to him, imparting wisdom that would protect him and his followers from the island’s evils. He was instructed to make offerings to purify the land, offerings to the gods and offerings to his ancestors.

Rsi Markandaya returned to Bali once again with a smaller group and performed a purification ritual before clearing the forest. Since then, the purification tradition, which includes burying symbols of the five cosmic elements – water, fire, air, water and void – before any construction of houses and temples has been continued. Rsi Markandaya realised that all human actions must encompass rites addressed to the three cosmic components of the world (Tri Loka), namely Bhur Loka, the underworld; Bwah Loka, the human realm; and Swah Loka, the divine realm. When these offerings are carried out, only then can humans find their place in the greater cosmos. This was the reason Rsi Markandaya gave Bali its name, derived from the word wali, meaning offering.

From there, he continued to venture westwards where he stumbled upon an enchanting place called Taro. It is there that he found solace and constructed a temple called Pura Gunung Raung. Clearing the forest surrounding Taro and southwards to Ubud, Rsi Markandaya felt the pulsing energy that attracted him to Campuhan, a place that became his most favoured mediation spot at the point of confluence of two rivers, Wos Tengen (right) and Wos Kiwa (right), that converge into a single stream. Where these two rivers meet is a ravine with a verdant hill called Gunung Lebah. Legend says that this environment is what attracted Dewi Danu, Goddess of the Lakes, to Bali in the first place. A sacred temple was built on Gunung Lebah in honour of this divine visitor. During this venture through the forests, Rsi Markandaya and company found many medicinal herbs and plants, as the source of these healing botanicals the area came to be known as ubad, the Balinese word for medicine.

In addition to Gunung Lebah Temple, Rsi Markandaya is known to have been responsible for the establishment of many important temples around the island, as well as introducing the subak concept, the shared irrigation system that still exists today. In short, Rsi Markandaya is an important figure to the foundation of Balinese Hinduism in its purest essence known as Agama Tirtha – the religion of holy water.

The Crystallisation of Place and Identity

Over the next 400 hundred years, plenty of temples and monasteries were built in Bali. This includes Gunung Kawi, the 11th century temple and funerary complex in Tampaksiring, northeast of Ubud; and the cave temples of Goa Gajah – historical sites that still exist today. This era saw one of the most notable kings who ruled all of East Java and Bali named King Airlangga, whose seat of governance was based in the present-day village of Batuan, southeast of Ubud.

During the 14th century, the Javanese Majapahit kingdom, led by Sri Kepakisan, conquered Bali from 1343 until the demise of the Majapahit empire. The 16th century saw a complete relocation of the Majapahit Kingdom to the island of Bali caused by the Islamisation of Java, which forced them to travel eastwards.

In 1537, the Javanese priest Dang Hyang Nirtartha, arrived in Bali. He was a Shaivite religious figure who was responsible for reshaping Balinese Hinduism to the religious practices and rituals that we know today. He was the founder of the Shaivite priesthood that is prevalent to present day Bali and viewed as the ancestor of all Shaivite pedandas. It was during this period that saw a significant blossoming of Balinese culture, a time in which the ancestral lineage of Ubud’s present day aristocratic families can be traced back to.

Of course, with their ancient lineage tracing back to the Javanese Majapahit warriors who invaded Bali, the princes of Ubud were held great esteem. With this the area was able to grow into one of Bali’s most well-known, well-respected dominions.

The Ubud Royal Family and the Great Warrior King

Kings of the past were referred to as Raja Bharata, Ancestor-God Kings, to the older generation of Ubud locals. This includes Cokorde Gede Sukawati, who established Ubud as a key Balinese princedom in the late 19th century; his sons, Cokorde Gede Raka Sukawati; and Cokorde Gede Agung Sukawati, the former King of Ubud.

Cokorde Gede Sukawati was arguably regarded as the last and most prominent of the noble warrior kings of Bali. In 1874, his father, Cokorde Rai Batur, rose to prominence when he claimed victory in a war against the kingdom of Gianyar. In 1891, prior to Mengwi’s fall to Badung and Tabanan, Cokorde Gede Sukawati spearheaded an alliance of Ubud, Peliatan and Tegalalang against Negara. He gained great success in his conquests, which showered him in riches and power. He managed to usurp control over a vast area that spans from the upland of Taro down to the southern villages.

He managed to expand his domain to an impressive 130 villages, displaying his competence in mobilising up to 18,000 followers with his allies. By the middle of the 19th century, he was the most wealthy and powerful punggawa of Gianyar, even more so than the King of Gianyar. His rise to power didn’t come with its fair share of obstacles, the more powerful he became the more of a threat he was to rivalling kingdoms including the kings of Klungkung, Bangli and Badung. His military expertise was unquestionable but he was cornered on all sides and required allies. When the Dutch arrived and demanded all Balinese kings acknowledged the suzerainty of the Queen of Holland, Cokorde Gede Sukawati saw this as an opportunity to form an alliance, and thus, Gianyar became a Dutch protectorate in 1901. As rival kingdoms were decimated by the Dutch, Gianyar and Ubud remained untouched.

Bali began seeing the changes brought by the new world as the Dutch expanded their colonial administration, building bridges and roads across the island, set up health services. They appointed kings and punggawa as salaried colonial government officials, and established schools in Gianyar and Denpasar. The Old Tjampuhan Bridge that crosses the valley over the Wos River, overlooking Gunung Lebah, is a remnant of this Dutch infrastructure.

In 1917, a massive earthquake struck Bali, claiming the lives of thousands of people and destroying many temples, villages and palaces throughout the island, including the Ubud palace. The palace household took up residence in temporary buildings built on the site where the Ubud market now still stands, before a new palace – Puri Saren – was constructed across the street and has since become the permanent residence of the royal family.

Development of Tourism

Bali’s tourism developed in the 1930s following the arrival of foreigners seeking to explore the exotic island. Ubud instantly became a top destination for these foreigners and this was in part due to the literacy skills of Cokorde Gede Agung Sukawati, who was well-versed in English and Dutch, and his business knowledge, in which he built guesthouses for these foreigners to stay at in Ubud.

His elder brother, Cokorde Gede Raka Sukawati, also played a crucial role in the development of Ubud’s tourism after he invited Russian-born German artist, Walter Spies, to come live and paint in Ubud. This catapulted Ubud into an art mecca, becoming a trend among foreign artists in their creative pursuit to find inspiration and work in Ubud — but it its seclusion away from the worries of a post-War Europe and the heaviness of the industrialised world was certainly part of the seduction. Ubud became well-known to the world through the works of these foreign painters depicting life in Ubud, along with painting exhibitions held abroad.

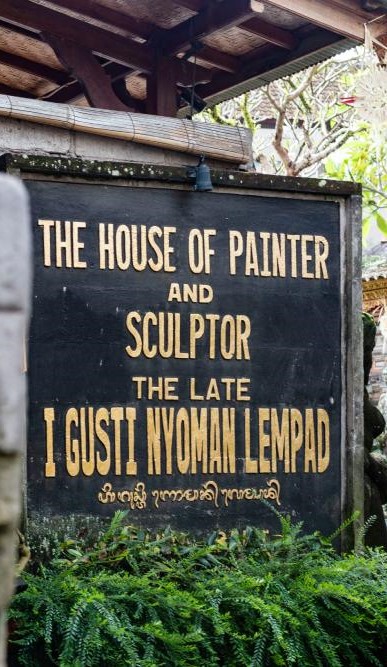

Spies along with other foreign painters such as Willem Hofker and Rudolf Bonnet hosted many celebrities including Charlie Chaplin and H.G. Wells. In 1936, Cokorde Gede Agung, Cokorde Gede Raka, I Gusti Nyoman Lempad, Spies and Bonnet established a painting association called Pita Maha, which was created to gather Balinese artists from around the island. They also brought gifted artists from across the island to teach and train the Balinese in the arts, further stamping Ubud as the artistic heart of the island.

Another famous foreign painter who made Ubud his home was Han Snel, a Dutch soldier conscripted during the Dutch reign of Indonesia. Following Indonesia’s independence, Snel applied for political asylum, built a studio with his new wife, Siti, and began to paint. His paintings piqued the curiosity of both the Balinese and foreigners through his refreshing fusion of both cultures.

In the 1950s, Spanish-American painter, Antonio Blanco, built a house and museum in Ubud, on a land that was gifted to him by Cokorde Gede Agung. This is where he houses many of his paintings, an eternal feminine painter whose romantic-expressive and dreamy work primarily featured women as the focal point. In the 1960s, Ubud saw a new surge of innovative energy with the arrival of the Dutch painter, Arie Smit, and the establishment of the Young Artists Movement.

Until now, Ubud has become a major tourist attraction that houses several museums throughout the area including the Museum Puri Lukisan, Agung Rai Museum of Art, the Blanco Renaissance Museum, and Neka Art Museum.

While Ubud has seen major developments since the island’s tourist surge in the 60s — with the development of its wellness experiences, culinary offerings, festivals and more — it has managed to retain the same, age-old charm that attracted people to it in the first place. Ubud is blessed with verdant hills, lush rice paddies, majestic landscape, tranquil surroundings, historical destinations and traditional markets, things that have made this unique locale a world-famous destination.