Asta Kosala Kosali is the traditional Balinese system of spatial and architectural rules that governs how buildings and compounds are planned, oriented, and proportioned. Though its details vary from village to village, the system provides a coherent grammar for organising the environment—defining not only where structures stand, but how they are approached, used, and understood.

Tripartite Cosmological System

The Balinese view themselves and reality through a cosmological lens of Hindu–Buddhist origin. They see the human being as a Bhuwana Alit (microcosm) mirroring and duplicating the larger Bhuwana Agung (macrocosm).

As a duplicate of the world, the human person contains both the gods that animate it and the “demons” that threaten it; and this is structured into three parts (tri angga): Utama angga (upper body and head), madya angga (middle or torso) and nista angga (lower body, genitals and feet). This mirrors the cosmic division into the divine realm above (Swah), the human realm (Bhwah or Madya Pāda), and the demonic realm below (Bhur).

This microcosm-macrocosm model is a Hindu-Buddhist concept, but was easily adopted by the Balinese because it fit so naturally into the indigenous cosmology, that of an island between sea and mountain, the prosperity of which follows the movement of water. The island is therefore also structured into a tripartite of cosmos: Utama mandala (the mountain, realm of gods and ancestors), madya mandala (agricultural plains, and human domain) and nista mandala (the sea, realm of decay and demonic forces).

This tripartite division is a repeated pattern across many scales, defining how spaces are organised. Human life is therefore structured according to the cosmos.

For example, this is repeated on the village scale, determining where the three main temples in the village (Kahyangan Tiga) are situated. The Pura Desa village temple is the purest zone (utama mandala), found on the highest part of the village; the shared ancestral temple, or Pura Puseh, is located in the middle (madya mandala); and finally the temple of the dead and cremation grounds, Pura Dalem, is considered the impure zone (nista mandala) and is therefore located in the most lowland area.

This same structure is found within a housing compound and also temple compounds, with this hierarchy from higher (pure) to lower (impure) – more on this below. Even on vertical structures this is visible, with symbolism of gods found on upper parts, and demonic symbology or depictions at the bottom.

The Orientation System: Kaja-Kelod and Kangin-Kauh

If the Balinese use the tripartition above to hierarchise their space, they use other another concept to organise their actions within this space. There is a directional axis that defines this, known as kaja-kelod, the Balinese version of “north” and “south” where the former is the mountain (upstream, the source of pure water) and the latter is the sea (downstream, receiver of waste and ashes). This is therefore an axis of relative purity – this is one of the central tenets of asta kosala kosali.

This axis is used to determine which actions are appropriate in what direction: people should sleep with their heads toward the mountains (kaja) and urinate towards the sea (kelod/ngelodang). Or for ritual processions, gods are carried towards kaja and ashes of the dead are taken kelod.

Then there is the second axis, kangin-kauh, which runs east to west respectively. This is defined by the movement of the sun: kangin, where the sun rises, is associated with birth and life; whilst kauh is the setting sun, associated with forces of darkness.

How these two axes intersect create a hierarchy of cardinal directions of where the most auspicious direction is kaja-kangin (northeast – mountain and sunrise), with the profane direction being kelod-kauh (sea and sunset). To complicate things further, these orientations are relative to the mountains, so for South Bali kaja is north, but for North Bali kaja would be south.

Asta Kosala Kosali Applied in the Built Environment

The Temple Complex

These two systems (tripartite zones and directional axes) constitute the basic spatial grammar of Balinese architecture, determining not just location but also movement, function and meaning.

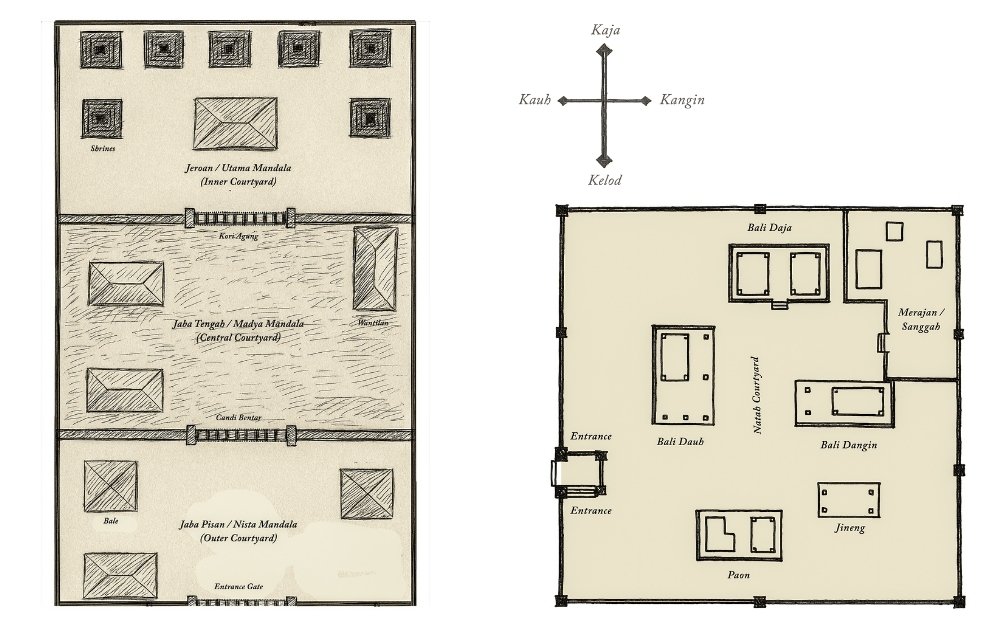

Architectural layouts will combine these systems to place specific buildings or functions to an area. A typical temple compound will be clearly divided by walled courtyards, separating three zones oriented to a certain direction. The innermost courtyard, called the Utama Mandala (jero pura) is the most sacred, home to the main padamasana shrine with two rows of shrines facing it. This is courtyard is situated in the northeast (kaja-kangin) of the complex, reserved for the principal rituals, prayers and offerings. The middle courtyard, Madya Mandala (jaba tengah), is for where ceremonial preparations take place, as well as dance performances. Finally, the outer courtyard, Nista Mandala (jaba pisan / jaba pura), is for public gatherings and general or less sacred activities.

Progression from one courtyard to the next is marked by monumental candi bentar (split gates) and kori agung (roofed gateways), reinforcing the passage from the profane to the sacred.

The Natah and Living Quarters

The traditional Balinese family home follows similar ‘rules’, but these are put into practice differently. The home is centred around the natah, the open courtyard space found at the centre of most traditional homes (typically 300 to 400 square metres). Multiple pavilions surround the courtyard, serving specific functions, each of which corresponds symbolically to a body part and a cosmic element – the compound as a whole reflects the tri angga of the owner’s body and the universe.

Starting again at the most sacred corner, kaja-kangin, this is where the family temple (sanggah / mrajan) is located. This is the ‘head’ and the most divine (utama mandala) area. One will find two rows of small thatched shrines with central rong tiga housing the family pratima (ancestral effigies), and the shrine dedicated to Surya (sun god) in the northeastern most corner. A ngurah shrine stands guard outside the family temple.

At the other end of the family compound (kelod-kauh) is the entrance, the most impure part of the compound representing the lower body (even ‘anus’), associated with Batara Kala, the lord of destruction. Typically two guardians and a protective shrine flank the entrance door, and just inside an aling-aling wall blocks a direct path ‘in’, as malevolent forces are believed unable to turn corners.

Then we have the central zone, the ‘torso’ of the compound where bale pavilions and rooms are arrange around the natah courtyard. Traditionally, different buildings will have their specified uses. The bale daja (northern pavilion), used for older couples or celibate family members (associated with purity), the bale dauh (west) for young and ‘active’ couples, the open-air bale dangin (east) is for ceremonial functions like tooth filings or preparing deceased for cremation. Finally, the most southern pavillion, bale delod, is for the elderly family, and often where the kitchen is found, close to the exit where ‘waste’ is also disposed, or animals also kept.

Building According to the Cosmos

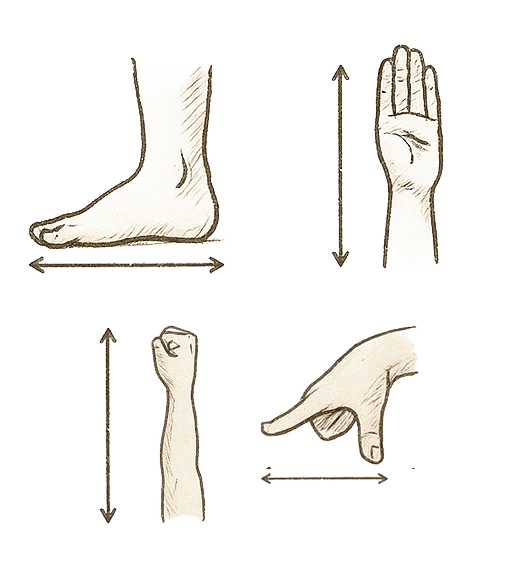

As the body is a mirror of the universe, structures are built in proportion to the human body. Traditional measurements in Balinese architecture are thus neither metric nor imperial, they are fluid, following the bodily dimensions of the structure’s owner.

This units include: the depa (armspan), hasta (length from elbow to fingertip), tapak (length of the sole of the foot), tapak tangan (width of the palm), nyari (span between thumb and middle finger) and ala (distance between tip of middle finger to the armpit). This is personalised design on a whole other level, ensuring that the structures are built to mirror the body, aligning with the cosmos.

It is the traditional Balinese architect, the undagi, who are responsible for building according to the cosmos, who must understand and implement the concepts of Asta Kosala Kosali. They are not your ordinary ‘contractors’ – erecting a building in Bali is considered a profound act that can disturb the balance of the cosmos. It cannot take place without the proper procedures, for it involves contact and negotiation with niskala, the intangible or unseen forces.

The process begins with a ceremony to ask the earth goddess, Pertiwi, for permission to open the ground (ngruwak tanah), and work may not start before consulting a pawukon calendar specialist to determine the most auspicious day and time. The first construction is the ngenteg linggih, the ‘confirmation of place’ ceremony, where a stake is driven into the reference point from which all measurements will be made – the owner’s then body proportions used as the standard, as mentioned.

The process begins with a ceremony to ask the earth goddess, Pertiwi, for permission to open the ground (ngruwak tanah). Work may not start before consulting a pawukon calendar specialist to determine the most auspicious day and time. The first construction rite is the ngenteg linggih — the “place confirmation” ceremony — in which a stake is driven into the reference point from which all measurements will be made, using the “owner” as the measurement standard.

For such projects, one must engage a fully-initiated undagi, capable of overcoming the technical challenges of traditional construction (materials, measurements, design), as well as knowing and performing and the necessary rituals to bring the work to its successful completion – and doing so in fully harmony with niskala forces and in balance with the macrocosm. Essentially the rules of asta kosala kosali promise that new buildings are in line with the Balinese cosmology.

Balinese Architecture in the Modern World

In Balinese villages – apart from the compounds of aristocratic and Brahmin families, which follow a grander variation of local architectural rules – all compounds are built to the same pattern. They stand parallel to one another, with the same size, the same type, and the same relative placement of entrance gates and ancestral shrines. This creates an extraordinary visual mosaic.

Sadly, change is inevitable, driven mainly by demographic and economic factors. The classical Balinese compound with its many functional buildings, was traditionally intended for a single pekurenan or nuclear family, often including grandparents. Commonly, the eldest son in regular-caste families (or the youngest in aristocratic families) was expected, upon marriage, to establish a new compound complete with its own family temple, thereby becoming a full citizen of the village. This system was only possible as long as free land was available.

That condition no longer exists. Land has become a commodity, and fewer people can afford to purchase enough to build the large compounds demanded by tradition. Today, instead of each son having his own new compound, the father’s compound is often subdivided among his sons, and its architectural structure is modified to meet new needs.

Now, individual Balinese – be it by economics, taste or land availability – will live in modern, closed-off homes, rather than the open courtyards. As for tourism, only a handful of the classic hotels reflect these traditional norms (though on a monumental scale). Other than that, reference to Balinese architecture is largely ignored. Shapeless buildings, with no defined sacred direction, spring up along the roads. Outside of sacred buildings, Asta Kosala Kosali, remains mostly in theory and sentiment, but largely ignored in practice.

How will this affect the island’s balance with the cosmos?