Balinese villages give an extraordinary impression of order. Houses are all identical and strikingly parallel in layout; with family temples, kitchens and rooms occupying the same relative position in the walled compound. Large temples, likewise, all have the same structure with their main shrines occupying the same kaja kangin (east-mountainward) corner.

This Balinese sense of order and harmony are based on principles of the Hindu-Balinese religion, and in particular its emphasis on balance between Man, God and Nature. Depicted as a microcosm – Bhwana Alit or “Small World”-, Man is expected to exist in his natural environment in a way, which conforms to the macrocosmic order of things – the Bhwana Agung or literally Larger World. In other words he reshapes his environment on the dual model of himself and the Macrocosm. Thus all architectural structures should reproduce the tripartite order of both the world and the human body, which are each divided into upper (utama), middle (madia) and lower (nista) parts. Every building, compound and territorial unit should thus have a head, a body and a lower body, respectively corresponding to the upper world of the gods (Swah), the middle world of humans (Bhwah) and the lower world of demons (Bhur). To practically apply these cosmological principles, a system of orientation is also needed. It is determined by the crossing of two natural axis, that of the rising and setting sun on the one hand, and that of kaja-kelod mountain-sea or, more precisely, that defined by the upstream-downstream axis (ulu-teben) on the other. Practically, this means that the head of any layout should be located upstream (ulu) and its foot downstream (teben); the structure should be tripartite. For the Balinese, Gunung Agung, the great mountain is the centre of spirituality and all buildings will refer to it.

The Balinese Compound

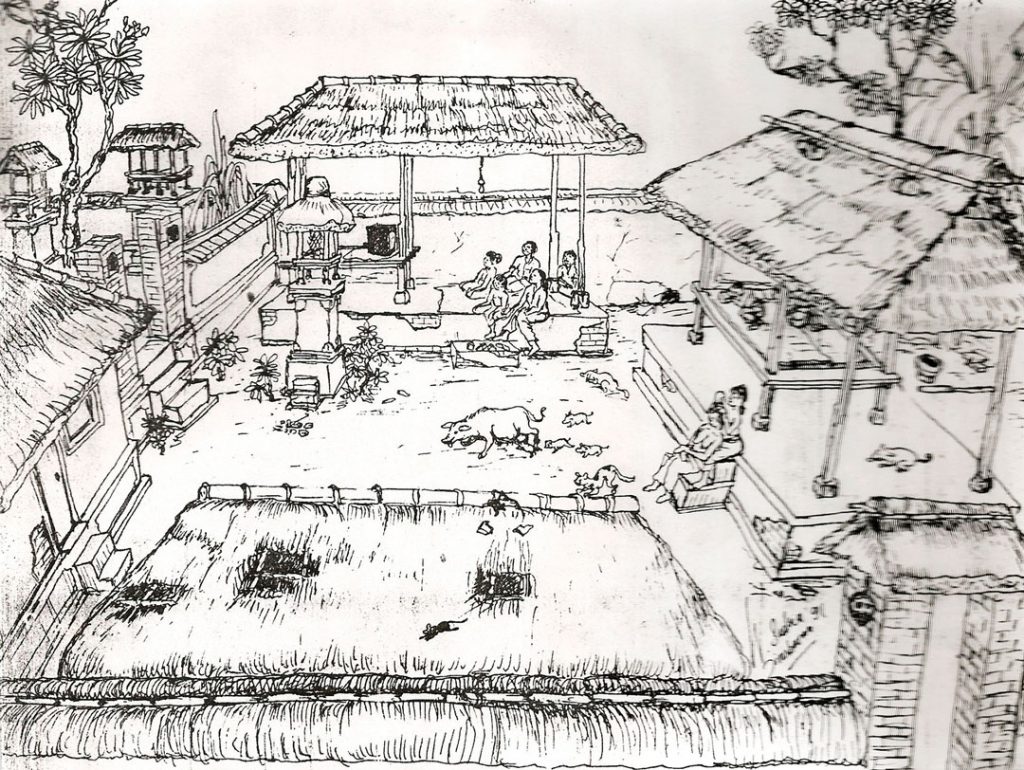

Let’s take a look at the typical Balinese commoner’s “house” or compound.

First, it should be emphasised that the Balinese do not live in a “house” in the Western sense of the word. Their living quarters are large compounds of 600 to 900 m2 comprising a number of separate buildings, most of them with verandahs that are the counterpart of rooms in the Western house. People spend most of their time “outside”, in the yard (natah), or on the open verandahs of the main buildings. The only closed spaces are the parent’s room in the bale dauh – to the west (dauh) of the central part of the compound – and the youth and children’s sleeping quarters, the bale daja, to the upstream-west part of the compound. The kitchen (paon) is located downstream and west of the compound, with the granary (jineng) to its east. Old people usually spend their days in the bale dangin pavilion, located in the central-eastern part of the house, while, just “above” it, the gods “reside” in a smaller walled yard located in the eastern mountainward part of the compound called the sanggah or merajan.

The occupation of the various buildings by the members of the family corresponds to the phases of incarnated life: the young live in the bale daja, the building nearest to the mountain from which they “recently” incarnated; with adulthood, they move to the middle-western pavilion (bale dauh); then, with old age, to the eastern bale dangin, the pavilion nearest to the family temple (sanggah or merajan) where their soul will be enshrined after death.

As explained above, the structure of the compound is on cosmic concepts: “houses” are seen as duplicates, both of the world and of the human body. Corresponding to the abode of the gods, the compound has a head: the family temple; corresponding to the middle world, it has a torso: the yard, complete with its arms: the various buildings of residence, and its navel: the Indra shrine in the centre of the yard; and, finally, corresponding to the lower world, it has respectively bowels, here the kitchen, genitals, here the gate, and even an anus, here the backyard refuse, situated “downstream” from the kitchen.

The Family Temple

Arguably the most important part of the Balinese compound is its temple, the sanggah or merajan, around which evolves much of the ritual life of the family. The temple consists of a small walled yard with several rows of small thatched buildings looking like puppet houses, the shrines (pelinggih).

The principal shrine of any Balinese family temple is the Sanggar Surya, located in its eastern-mountainward corner. Toward the rising sun, Surya, is the name of the Sun God, the origin of all rays. This shrine is therefore that of the Almighty, from which all lesser gods – or rays – originate. The ways the other shrines are situated in relation to the Sanggar Surya also illustrates the hierarchy of the godly, in two rows of shrines, one running from east to west and the other mountainward to seaward. The right angle where the two rows meet is the place of the Sanggar Surya shrine. The following pattern is the most common: on the westward row, the first shrine one sees is usually that of the Goddess of agriculture Dewi Sri and of the God of wealth Sedana. Their role is a reminder of the agrarian foundation of Balinese culture. Further westward is the taksu (inspiration) shrine, through which the individual is bestowed with his powers and talents. Beyond is a guardian shrine.

Downstream of the central sanggar surya shrine is located the row of ancestral shrines, the closest to the sanggar surya being the shrines of the remotest ancestors. The first to come, in the main sanggah/merajan, is often a shrine with a deer’s horn (menjangan sluwang), which denotes that the family claims its origins to as far back as the Majapahit empire. Next follows the ibu or paibon which represents the ancestors from the sub-clan temple of origin; then comes the rong tiga shrine for the worship of the closest ancestors, where the family’s dead are enshrined after completion of the cycle of death ceremonies. Finally, at the extremity of the row, comes another guardian shrine.

During temple festivals, every 210 days, the shrines are dressed, i.e. wrapped in coloured clothing, as a sign that the gods are visiting.

Evolution of the Compound

Bali has long had a surplus of available land. This has enabled the traditional architecture to remain virtually untouched. The older sons, in commoners’s families, or the youngest ones in aristocratic families, were supposed to open their own new compound on free village land upon marriage, when they became full citizens of the community. When village land was becoming scarce, they would move inland and open the forest, creating a “sister village”. The architectural system of Bali has thus duplicated itself all over the island.

The functioning of this system, though, is possible only with reserves of free dry land. This is no longer the case in Bali. Land is a commodity, therefore scarce.

Now, more often than not, instead of opening new land and building new compounds, brothers have now to share their parents’ compound. They end up transforming the old traditional buildings into inward-oriented, western-style houses: the verandahs shrink in size or disappear altogether, rooms are added, new materials are used. The change may even affect the temple. Sometimes the whole set of shrines is transferred on to a terrace. More often, though, especially in the cities, the complete temple is substituted with a single shrine, the Padmasari, which sums up all the main functions of the temple, and through which it is possible to address one’s village ancestors from a distance (nyawang).

The Balinese architectural landscape is thus fast changing. It is increasingly difficult to find Balinese architecture preserved in its original shape. Instead of the airy traditional compound with its central yard and verandahs, more often than not there are now cramped rows of buildings of an undefinable, often kitschy style. Bali is losing its homogeneity, and thus, its uniqueness.