Most of you, dear readers, when coming to Bali, already have a certain idea of the island. An iconic idea, which encompasses, as you probably know, just a small part of reality. So you must certainly have been told that Bali is the only Hindu island in Indonesia — and you have been told so by Western media, which always likes to over-emphasize the differences between Islam and the rest. Reality is indeed more complex. The Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore had perceived that, when upon visiting Bali in the 1920, he famously said, ’I see India everywhere, but I don’t recognise it.’

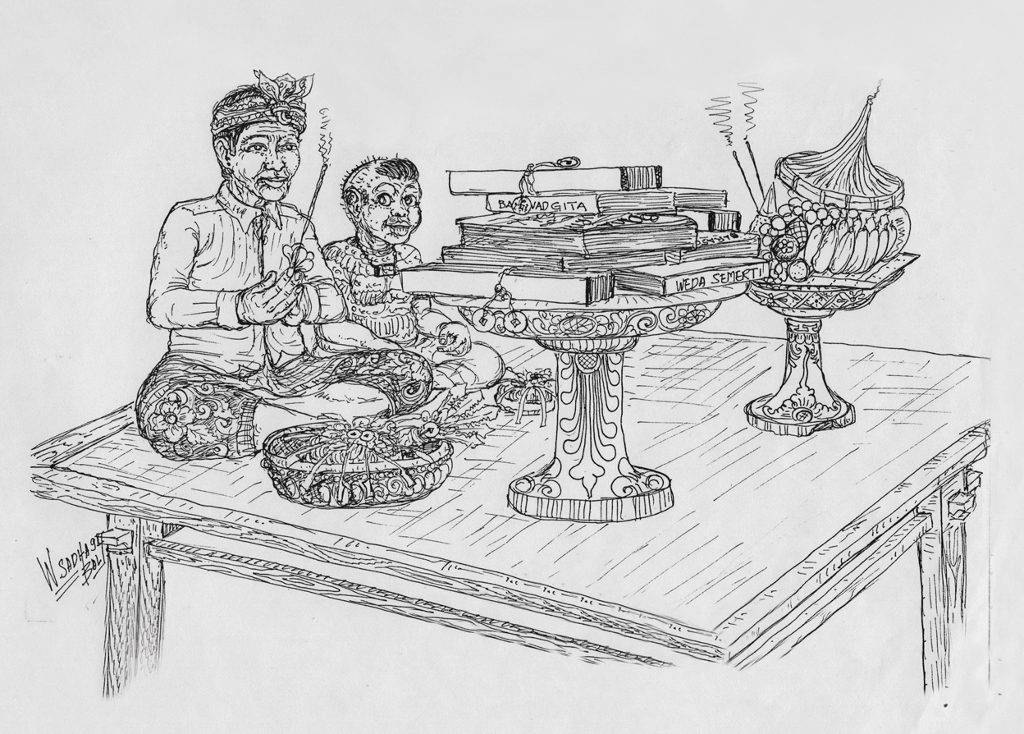

Yes, even though historians will tell you that Indianisation started over 1500 years ago, it is still ongoing and – for many Balinese, a recent process. For example, if you attend an official event in Bali, you will witness the priest in charge – there are always prayers for any event — uttering his prayer in the most perfect kind of Sanskrit. You will have good reasons to admire him: fifty years ago, no one knew any prayer in real Sanskrit. The pedanda high priests used mantras in a mish-mash of Archipelago Sanskrit that was nearly undecipherable. And they addressed their prayers to the ’gods’ – yes, to the plurality of them, often mentioned one after the other, to emphasize their accumulated power. Today the ’gods’ are gone; or rather they are silenced and put into the background: after uttering his Sanskrit mantra, the priest above will carry on with his a prayer not in Balinese, but in Indonesian, addressing it to the one only God, Sang Hyang Widhi. If he then mentions some ’gods’, he will never fail to add that they are ’manifestasi’ (manifestations) of Sang Hyang Widhi. Polytheism is thus swept under the carpet.

All this is very interesting because, until the Balinese religion was recognised in the late 1950s, this Sang Hyang Widhi was virtually unknown. Meaning fate, he was picked up from some obscure traditional text and ’re-engineered’ into the Only One, so that the Balinese ’religion’ – or the somewhat amorphous compound of beliefs that was this religion — could be transformed into a seemingly monotheistic religion from a polytheistic one. This enabled it to gain acceptance or tolerance from Moslem clerks who had until then been frustrated in being able to classify ’Balinese religion’ as a ’religion of the book’. The Balinese could thus escape the sad condition of ’kufur’ or polytheist. If this did not give them an easier access to Javanese Moslem women, it enabled them at least to go on with their life as if nothing had happened.

To be honest, the pressure was not only external – from Islam and also from Truth-hungry Christians — it was also internal. It had existed well before independence, from 1900 onward, as Balinese were being drafted into the modern educational system. As they were initiated to the Dutch worldview, more and more educated Balinese were eager to give sense and meaning to the rites they were performing, as well as to the pantheon of gods they were addressing their prayers to. Indeed, apart from the Indian gods mentioned in the old manuscripts, there were also many local gods with strange names such as “the lord from under the Kepuh tree” or the “the lord from Solo”. It is no surprise they yearned for a faith, an explanatory system, that would add coherency to the amorphous compound of beliefs changing from place to place they had to deal with. Just put yourself in the shoes of a typical young Balinese aristocrat in the 1920 to Malang sent for schooling. When asked by his teacher to explain the tenets of his religion, he could not simply explain that he followed the “great god” (ratu gede) of his village and show a barong picture. If he did so, he would immediately be classified as a pagan and, if the school was Catholic, would be sent to the priest in charge for possible conversion. But if he told his teacher that he was ’Hindu’, as the Dutch teacher insisted he was, everything would be more or less okay. The Dutch had concluded from the study of manuscripts collected from Brahmins that Hindu gods were worshipped in Bali. So they concluded that all Balinese were Hindus, unaware that this so-called Hindu tradition was limited to a minority of the population, that of the princely palaces and Brahmin’s mansions. For the great majority of the population – and even today among the older members of the peasantry — the name Hindu and the concepts associated with it did not mean much. What mattered to them is what happened to their dead: the dead have to head back home, to the family temple, to be worshipped there. The rest is of little importance. They still hold this belief today.

So, once the Balinese saw themselves classified as Hindus, they thought that they had to become so, and they called up the whole written tradition and the institutional system for the purpose. In the 1950s, intellectuals held meetings to structure their religion and they eventually came up with a set of 5 core beliefs, the Panca Sradha, which, when taught in schools would allow them to be formally classified as Hindu and be recognised by international Hindu organisations. Those five beliefs are: belief in Brahman, the Godly principle or Widhi; belief in Atman, the existence of a soul; Belief in Karmaphala (the fruits of one’s deeds); Punarbhawa, belief in reincarnation; Moksha, belief in the ultimate merging of the soul and the godly.

Those beliefs did not previously exist as such among the population. The godly was as ill-defined as it was numerous; as for the soul, its place was above the mountain, not merging in God; and if it came back, it was among its descendants, with little attention given to karma and the chain of reincarnations. The religion of ordinary people was a cult of ancestors.

But anyway, once the Panca Sradha was proclaimed, all was done. Until today, it is taught around Bali and beyond, through schools, the media and the interventions of the Council of Hindu Affairs (Parisada Hindu Dharma). Internally all is also being done to adapt or bend the living tradition (and living vocabulary) to the demands of the new orthodoxy. So, little by little, the memory of the mountain and lake gods disappear: they become “manifestations” of the Only One; as for people, they reincarnate less often among their kin, as people with a bad karma are supposed to come back as dogs and insects.

Yes, after 1500 years of Indian influences, Bali has finally discovered religion and Hindu orthodoxy. There is a hitch though: over there, beyond the Bali Strait, there are other people who have also rediscovered orthodoxy and its related identity – that of Islam. Let us hope there will never be a clash of identities.