Indonesia is a nation of 273 million people, 88% of whom are registered as Muslim. Bali is the only region of the country where the majority of the population is Hindu – although Balinese Hindus, make up only 1.7% of the Indonesian population. In Bali, 90% of the population is classified as Hindu, but the latest census does not include the inflow of mainly Muslim migrants who have settled in the island since the 1990s.

Bali has been in contact with Islam since the 13th century, mainly through the spice trade network between the Malacca straits and the Java and Arafurara seas: No Muslim ruler has ever invaded Bali, but some Muslims settled as traders or specialists such as doctors or astrologers, while others have been brought as followers and/or soldiers of Balinese kings during the latter’s expansion to nearby islands (East-Java/Blambangan) to the west and Lombok to the east from the 15th century onward. Due to these historic relationships, Muslim-Balinese have coexisted peacefully with the island’s Hindu-Balinese majority up to the present day. Even the Kuta Bombings of 2002 and 2005, engineered by radicals from outside the island, have not significantly altered the tolerance of Islam in Bali.

The Muslim communities of Bali are not homogeneous. Not only do they have different histories, they also correspond to different ethnic groups, each with its own language, tradition and its own form of Islam. The level of interaction and integration with the Balinese is in each case different, as is their culture and range of practice of Islam.

The oldest Muslim community in Bali is found in Gegel, on the outskirts of the town of Klungkung. It is said to date back to the days of the Majapahit in the 14th century. However, as it belongs to an urban space, it has lost most of its traditional features.

More original are the Buginese Muslim communities. The Bugis, a people from South Sulawesi, left their island of origin after the fall of Makassar to the Dutch in the late 17th century. They settled in several coastal areas of Bali and became the local king’s favourite mercenaries until the middle of the 19th century. Today they still make up the urban core of cities such as Singaraja (Tuban) and Negara (Loloan). As archipelagic traders, they have retained through the centuries constant contacts with other Muslim people from the archipelago and their interaction with the Balinese have been mostly limited to trade and political contacts.

The case of the Sasak, however, differs completely. The Sasak became a subject people of the Balinese kings of Lombok after the occupation of this island by the Karangasem nobility from Eastern Bali in the 17th century. When the Balinese occupied Lombok, a syncretistic brand of Islam was already prevalent on the island. Later, Sasaks were brought to Bali by their Balinese lords, and they reproduced there the complex syncretism that was theirs in their island of origin. Nowadays, even though some Balinese Sasak communities from East Bali have accentuated their Muslim characteristics, many still intermingle with the Balinese to the point of often being almost indistinguishable, such as in Batu Gambir.

Another interesting community is that of the archaic Javanese village of Pegayaman, set up by Javanese followers of the slave-trader king of Singaraja Panji Sakti at the turn of the 17th century. In spite of some recent “purification” of their rites under outside influences, they still retain to this day some peculiar Javanese ‘Muslim’ traditions such as the “tumpeng” offering (the pyramid made of rice) prepared for the prophet Muhamad’s birthday.

From the middle-19th century onward, other Javanese Muslim communities sprung up in Bali, mainly in the new urban areas created by the Dutch colonization. From a religious point of view, they practiced one of the two main brands of “Javanised” Islam: the first one, known as abangan, carries many of the mystic concepts of Sufism blended in a variety of combinations with stories, beliefs and concepts inherited from the Hindu-Javanese pre-Islamic tradition; whereas the second, carried by the coastal trade networks is more orthodox in outlook, and very similar to that of the Bugis discussed above.

Amongst these communities of Islam in Bali, small communities of Hadrami Arabs and Punjabi Indians also settled in Bali in the wake of the Dutch colonization from the late 19th century onward. Almost 400 male Arab migrants from the Hadrami of Shibam arrived in Bali from 1870 and the last 1920s (Barth 1993), most of whom later married with Balinese girls who converted to Islam.

Revivalism has proceeded in Bali as an ongoing process since the beginning of the 20th century. Before colonisation, Balinese Muslim were traditional subjects (panjak) of the local kings. Participation of royal rites, exchanging of women (with conversion of women to Balinese Hinduism), and participation in Hindu village rituals and festivities were common occurrences and led to increased Balinese influence. But with colonisation, Balinese Islam became increasingly oriented towards the Muslim world of the rest of the archipelago, and beyond. Young, local Muslims were sent to study in Java and even to Mecca. When they came back, they automatically became ulama, teachers of the holy Quran. Thus spread little by little an updated brand of Islam.

The spread of archipelagic-Islam differentiated from village to village. It is at its maximum in places open to the outside world such as Denpasar where the Dutch had their administrative centres and where there were important Hadrami communities ; but it was minimal among the rural Muslim communities that remained bonded to the local royalty and to their neighbouring Hindu-Balinese environment. Owing to this varied penetration of outside influences, Balinese Islam still retain to this day many nuances of their surrounding communities.

Yet there is no doubt that a process of Islamic Revivalism is on. It has spread to Bali through two great Java-based organisations: Muhammadiah, and Nadhatul Ulama. The first, wary of Islamic mysticism and Sufism, emphasizes a purification of Islam from all non-Islamic cultural elements and as such condemns the cult of Islamic saints. Its influence rests mainly on a network of “modern” urban school based on the national curriculum with the adjunction of religious teaching. The second is often openly Sufi; it hosts Sufi brotherhoods such as al-Quadiriah and emphasises a mystic approach that may – like for example in Seseh – enable shared rites with Hindu-Balinese around a holy tomb of a local Muslim saint.

As a whole however, tolerance still prevails for Islam in Bali, even though there is an underlying tendency toward social separation between the Muslim and Hindu-Balinese communities. A new kind of Balinese tolerance may well have to be invented. A tolerance based not on the affirmation of “sameness” between Hinduism and Islam, but on the acceptance of their total difference. This is a challenge for the future.

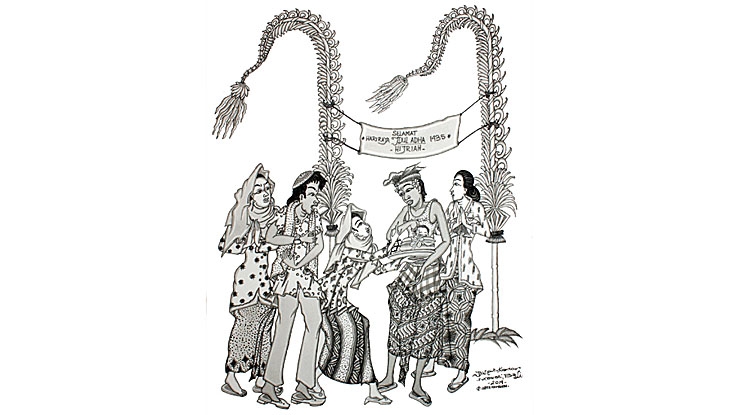

May you spend a great Holy month of Ramadhan in Bali!