Jazz, as Stanley Crouch wrote, predicted the civil rights movement more than any other art in America. Before it catered to popular audiences, the genesis of jazz has been symbolic to the African-American struggle for racial equality.

The message ‘when words fail, music speaks’ by poet Hans Andersen profoundly resonated in jazz music at the time, particularly during the Civil War. Eulogised as one of America’s original art forms, jazz was born in 1910s New Orleans by the African-American community who married their musical roots: blues and ragtime.

Then, came Kansas City Jazz and Gypsy Jazz in the ‘30s; faster, danceable ‘fine art’ Bebop and the smooth Calm Jazz in the ‘40s; and from 1960s onwards, jazz improvisation incorporated rock and electric instruments. Though there are opposing arguments as to who jazz ‘belongs to’, the rise of jazz throughout its many lifetimes became less attached on black innovation and history, and more about the commercialisation of what is seen as a profitable industry. As a result, it began to lack the essence of jazz as something more cavernous than sweet rhythms and rich harmonies.

Faced by negative social conditions that lingered after the Slavery Abolition Act, music has been instrumental to the African-American experience in the United States. Black people found comfort and peace in their music. It turned to be a vehicle to translate their anger and desire for change into a positive energy that fuels harmony and unity in the wake of discrimination. It’s one of the strongest forms of Pan-Africanism.

Before hip hop in the ‘80s, jazz was the ‘politically-charged’ work of art that created a sense of identity and social cohesion for black musicians. Whilst often referred to as ‘black classical music’ or ‘negro music’, commercial success was achieved by their white counterparts; and they were seldom credited for their innovation, talent, and most crucially, their unified voice.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. claimed jazz as ‘America’s triumphant music’ and that the search for identity among African-Americans was championed by Jazz musicians who were ‘returning to their roots’ in a multiracial world.

Speaking at the Berlin Jazz Festival in 1964, he elaborated on the importance of jazz:

“Jazz speaks for life. The Blues tell the story of life’s difficulties, and if you think for a moment, you will realise that they take the hardest realities of life and put them into music, only to come out with some new hope or sense of triumph.

And now, Jazz is exported to the world. For in the particular struggle of the Negro in America there is something akin to the universal struggle of modern man. Everybody has the Blues. Everybody longs for meaning. Everybody needs to love and be loved. Everybody needs to clap hands and be happy. Everybody longs for faith. In music, especially this broad category called Jazz, there is a stepping stone towards all of these.”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr

Not only did jazz music stand as an analogy to the spirit of activism, black jazz musicians embodied the cause themselves and aspiring musicians were finding ways to assert themselves musically. Jazz was the artistic parallel to the struggle; as just the act of performing, of putting the spotlight on black men and women on stages beckoning to be heard as artists, was a ‘rebellious political act,’ as pointed out by Ingrid Monson in the Black Music Research Journal.

Utilising their stardom, these musicians added their voices to the growing movement towards promoting racial equality and social justice. Here are some of the influential names in jazz, pivotal in the fight for civil rights in North America.

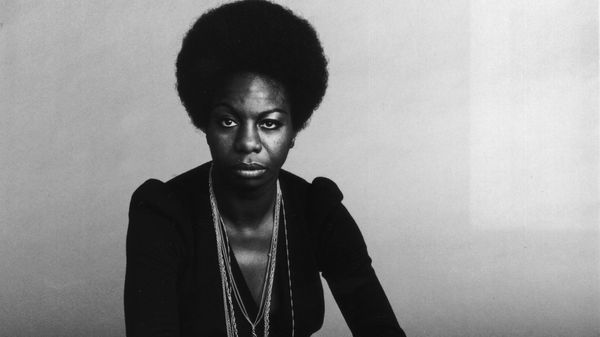

Four Women (1966) by Nina Simone

“My skin is black / My arms are long

My hair is woolly / My back is strong

Strong enough to take the pain / Inflicted again and again.”

Simone introduced a song she had written about what she called ‘four Negro women’, that paints a story about black women in America. But the deeper weight suggests a history of long-suppressed anger and emphasised resilience. Her intention to depict the injustice and suffering of African-Americans was misinterpreted as ‘racist’ for drawing on black stereotypes, subsequently led to the banning of the powerful number on major radio stations. Simone was among the most passionate, outspoken, and talented musicians and activists, she never backed down.

(What Did I Do To Be So) Black and Blue (1929) by Louis Armstrong

“My only sin

Is in my skin

What did I do

To be so black and blue?”

Armed with a trumpet and a voice, Armstrong played a part in reshaping American music and race relations. Though criticised for widely performing before homogeneously white audiences, on the other end of the spectrum, he was praised for ‘teaching’ white Americans the virtues of the black aesthetic. He became a cultural ambassador for the United States during the Cold War, travelling the world and performing jazz.

Strange Fruit (1939) by Billie Holiday

“Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.”

Composed from a poem by Jewish poet Abel Meeropol, the song was inspired by a harrowing photo in 1930 of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith hanging from a tree above a mob of white people, seen smiling and satisfied at the result of the lynching. Nine decades later, the song still rings close to home, singer-songwriter Bettye LaVette said, explaining why she has chosen to release her own version of the song on her upcoming album Blackbirds.

Fables of Faubus (1959) Charles Mingus

“Oh, Lord, don’t let ‘em shoot us

Oh, Lord, don’t let ‘em stab us

Oh, Lord, no more swastikas

Oh, Lord, don’t let ‘em tar and feather us!”

Mingus was known for his rage and forthrightness in the limelight that was undoubtedly justified when he responded to the 1957 Little Rock Nine incident in Arkansas with a composed piece criticising Jim Crow laws. The protest song was directed to Arkansas governor Orval Faubus who instructed the National Guard to prevent racial integration despite the desegregation of the public high school. The original instrumental song appeared on Mingus Ah Um (1959) under Columbia Records who rejected the recording of the lyrics. Mingus finally recorded with vocals in 1961 under Candid Records.

Honourable mention:

Alabama by John Coltrane

Can an instrumental song be as influential as poems and lyrics? In response to the 1963 bombing of 16th Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, Coltrane composed a powerful song with no words. The event that killed four young girls and injured over 22 other people was a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement that spurred the Civil Rights Act 1964. Music historian Craig Werner described Coltrane’s intricacy in his patterned saxophone lines ‘on the cadence of Martin Luther King Jr.’s oration at the funeral of the four girls who died.’

Listen to the complete line-up of instrumental Jazz numbers throughout history: