You’ve heard about reincarnation, right? Of course you have. But my guess is that you have heard about the formal, reformed-Hindu version of it, “You will reincarnate as a dog if you behave like one”, meaning, you will bear the consequences of your deeds in your future incarnation(s).

While some narrow-minded Balinese will insist this is the “truth” of Hindu religion, most will tell you that “truth” is of little importance. And indeed, in Balinese tradition, you actually reincarnate among your kin. Deep down, the cult of Ancestors side of the local religion prevails over its Hindu side, even though both deeply intermingle.

People often say, Ancestors are “water” (yeh). And to incarnate is to come down as “titis”, or as “drops” of water from the “old country”, the ancestors’ abode high above the mountains. Souls normally incarnate again only once they are ready, i.e. after they fully have paid for their sins in “the field of sorrow” (tegal penyangsaran) or purgatory, where they have been tortured by Yama’s demons. Those which try to leave the purgatory before their due time unavoidably end up in an abortion or in a child’s death–and thus find themselves back to square one, in the field of sorrow they have just left. People say that those souls tried to cheat and have to be punished.

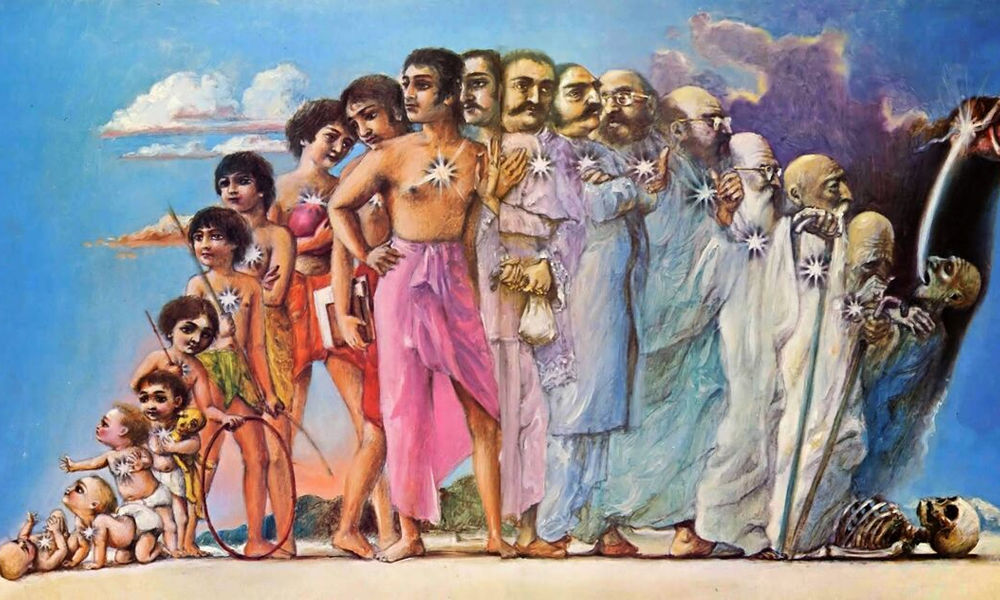

To have a child in proper condition is to pay proper attention to its soul’s incarnation. Balance is in the matter paramount, first of all at the level of the parents’ sexual behavior, which should be kept under tight control. This is symbolized in Kantor’s illustration, which shows the god of love Smara and his consort Ratih (the moon) overseeing the love scene below.

Another thing is that it is not just anyone that is incarnating. It has to be an ancestor’s soul –shown by the old man on the illustration. But in order to have the right soul coming down, all should be well prepared, including the right offerings and the right prayers. And one should address one’s request at the right place.

The most common is at the “Guru”, the three-door altar found in all Balinese family temples. If one’s prayers (nakti) there fail to fulfill their purpose, one may then go to a “specialized” altar , usually located in the middle of some preferably haunted (tenget) forest or the slope of some mountain. Most famous for the purpose are the Ratu Brayut shrines – the shrines of the ancestral figures of Father and Mother Brayut, known to have had many children.

Love making itself is not the issue, even though there are ways to make male or female children. I won’t tell you if you must push right or left! But it can work. Then, a sign (pawisik) will tell your wife that she is pregnant: this means the soul has found a place to come down through the meeting of the “white desire” (kama petak) with the “red desire” (kama bang). From that time on, the ancestor is there, waiting to come out in birth. When he/she does so, he/she is called as a “dewa” – an incarnating god.

Let us pass over the various ceremonies of birth and after-birth. The most interesting, and what makes people most anxious is: who is incarnating? No need to overly speculate. There are mediums (balian) whose job is to intercede with the “invisible” world (niskala). If you find a good one, he/she will find out for you, which is usually done on the 12th day after birth.

“Ding-ding-dingding-dingding,” the priest’s bell jingle jingles for a long-long time while he mutters mantras addressed to the Lords of the three worlds. The smoke of the burning incense is wafting over the nearby altar, offering “stairs” to the gods and ancestors to come down and “sit” (napak) on the requesting shaman (balian). Two women helpers are coming and going with offerings. But Nyoman Kemprot does not pay attention: he is holding in his hands a baby girl a few days old, and he, as well as all his relatives present, want to know who it is indeed who has thus come down from the ancestral abode, and whether he/she wants to be given something in particular for the upcoming otonan (first anniversary in Balinese 210 day calendar). But he does not have to wonder too long. His mantras become a jumble of inaudible soundshe shudders and his eyes turn white .

The incarnating soul is obviously having difficulty to express itself, but it finally blurts out, in a halting, hoarse feminine voice: “Hey, you who are hearing me; I have been erring too long is the world ‘over there’ (kedituan), until now I have found no place to come down and ‘ask for rice’ (nunas nasi) – meaning incarnating –; so I have no other choice than to incarnate again among you, children; but will you be able to look after me?” “We will of course look after you,” replied Nyoman Kemprot, “…but please tell us who you are…” “I am Ni Kerti!” “How is it possible that you come down?” asked Nyoman Kemprot, who knew that Ni Kerti had married and had begotten many children, and thus become a member of her husband’s kinship group. She should have incarnated in the latter’s clan. “I never took leave from my ancestors when I married,” replied Ni Kerti through the balian’s voice, “I am not bringing any wealth with me, and don’t ask anything. Just let me come down again among you.” Then the balian went silent.

There was no doubt to have. Nyoman Kemprot was sure that it was his dead female cousin who had come down. She had forfeited her duties when not taking leave from her ancestors at marriage – a ritual obligation as women have to follow their husband’s clan. And now she had to pay for it in a strange way: By coming back among them…

(Based on information by Wayan Sadha)