“For the Balinese, the village ones I mean, those little touched by modernity and Brahmins’ influence, sex is an obsession. It can at times take a physical form: after all it was pretty common until recently to forcefully kidnap a woman to marry her. The subsequent wedding cleansed the injury. What we now call a rape was simply called ‘to take a woman’ (ngejuk). “My grand-father did it, in the open, catching my grand-ma in the market place”. Who is telling this? A reputed man of letters, who does not hide anything, except his name.

“Theese ngejuk marriages are less frequent today, owing to the development of education,“ he carries on. “But they certainly still occur. By ‘taking’ a woman, the man is showing his virility. No fuss about that. What matters to the villagers is that he be responsible, meaning that he announces his feat to all and marries the abducted woman.”

Yet, such frankness is becoming rare among the Balinese. Today’s women hide their erstwhile world-famous breasts (anyway badly damaged by tap water and Mac Do), and men their feats. Moslem moralisation and Western women’s lib have crossed the Java Strait to Bali and changed the discourse, if not the deeds of all. Yet, with patience, and the right network, one gets stories, some from the past, others from the present, that all point to the odd combination of sex and the sacred in many aspects of Balinese life.

There is no worse fate for a Balinese couple than to be childless, and have no son. To have a sentana son, who will perform the rites due to dead parents and ancestors, is the dearest expectation of all Balinese. They are ready to go to any lengths for this single purpose, often under the wrap of the strangest beliefs, conscious and unconscious, as shown below.

One of the oddest sex-related traditions was one still pervasive among the Klungkung’s king’s subjects until the post-independence period (1945). The king, according to a belief held by local people, was considered as a ‘god incarnate’ (batara nyakala). Of which god? No less than Batara Tolangkir himself, the ‘Lord of the Mountain’. Hence his role as guardian of the Mother Temple of Bali, the Pura Besakih, at the foot of holy Mount Agung.

Yet, it is not the “cosmological” sexual quality of the mountain that is here of interest to us, but rather what this implied for the king and his subjects. As we all know, young married women do not always easily fall pregnant. This happens in Bali as elsewhere. But in Klungkung, usually among the lower ranks of the aristocracy, there was a peculiar way out of this conundrum. The impatient husband would take his wife to the king and invite him, as a “god incarnate”, to impregnate his wife. There was no jealousy. On the contrary: this was done in style, with gamelan music and offerings. After all, the ‘god-incarnate’ was doing him a real honour. His childless wife would stay at the court and ‘serve’ the king-god until she got pregnant. Only then may she return, again with due rituals and music, to her sanctioned husband. Did the latter object? No, he had no reason to, since his wife was to give him a godly child. In fact, I dare add with dry humour, it was not the husband who was jealous, but the king-god, the Batara Sekala: before the husband may start making love to his wife again, he had to wait until after the birth this godly child. You can guess why – the king-god could not allow his godly sperm (kama petak) to mix with that of a lesser male. Doesn’t all this remind you of a famous story?

Today, there are no more ‘god incarnates’ in Bali, but there are places where batara gods, happen to come down to earth and reside there for good sexual reasons. Some are endowed, or so people say, with the power to enable women to become pregnant. Many of these spots feature phallus or vulva-shaped natural oddities such as stones or tree roots. The way their residing gods are called – such as Batara Purus Gede (Big Phallus god) for males or Batara Luweng Luwih (Beautiful Vulva Goddess) for females, leaves no doubt about what they refer to and their fertility-enhancing function. Indeed, once a phallus or vulva-shaped spot has been locally identified, a woman or a couple will someday come to pray and ask the god for a child. If pregnancy ensues, other local people will hear about it and come in their turn to ask for a son. Then, out of gratitude, someone will build an altar, and later someone else a surrounding wall.

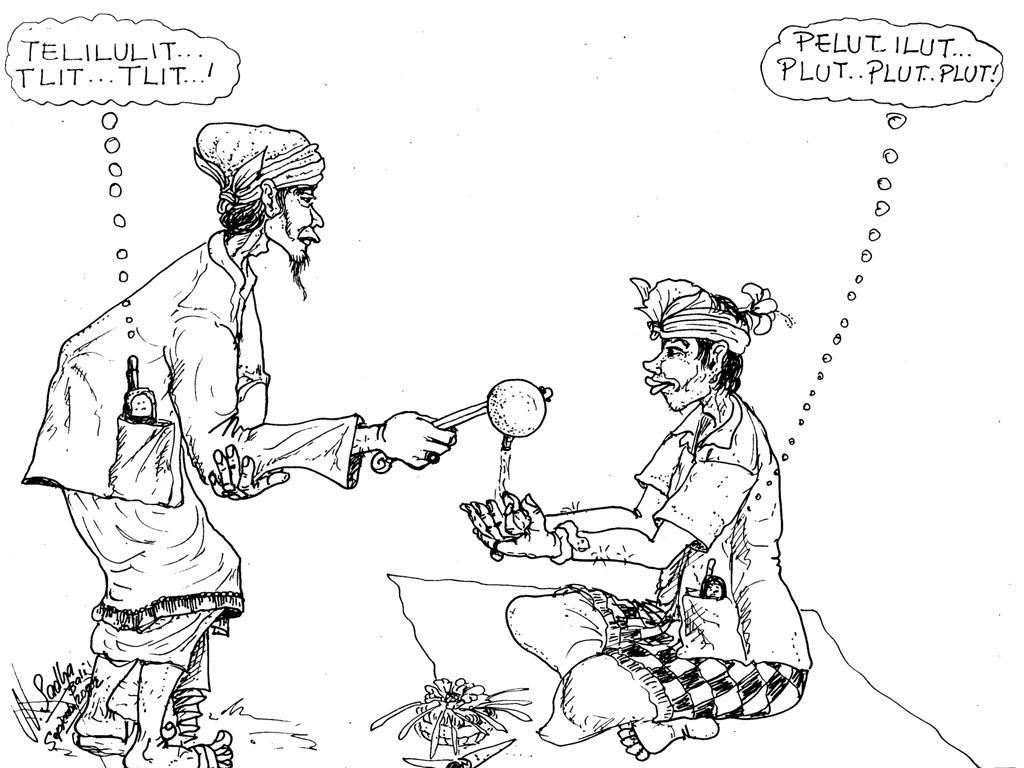

The oddity has now become a temple. A priest has been appointed to look after the supplicants. Now, it is not individuals who beg for the god’s favour, but the ‘facilitator’ mangku priest, who has the knack for the request of pregnancy to be granted to his visitors. The mangku sets the offerings and leads the prayer before addressing the god: ʺOh you, Big Phallus god, may you grant a sentana heir to the young couple present in front of you. May this heir’s path, down to earth, be a smooth and long one (Ratu Batara Purus Gede, ledang mapica sentana ring jadma mapekurenan puniki, mangda landuh wreddhi ayu pemargin ipun). He then takes the holy water ‘created’ by the request, bathes the phallus god with it, sprinkles it to the supplicants who then drink it three times… The following phase will take place in the supplicants’ bedroom when, before engaging in their love play, they will implore some long-waiting ancestor to come down as sentana among his descendants… I don’t know whether this brings enthusiasm to the act or the opposite. Make your own guess.

Yet, the demand for sex is not always that of humans. It may be that of ‘gods’ too. For example, a few years ago, in the village of Abian Gombal it so happened that several children were, for unknown reasons, taken by sudden bouts of crying, from pain. Worried parents, modern-minded as Balinese secondary education now makes them, took them each to the doctor. Their offspring were probably ill, they assumed, and a few pills would cure them. But the pills did not do the expected job. The children continued crying and complaining. It so lasted until one of the parents reported the occurrence to an old man of his neighbours. The old man, a wise one, ‘knew’ the cause of the ‘illnesses’ and the cure, he said. The children had probably crossed the local river at the wrong spot. By doing so they had disturbed in the act the beautiful ‘goddess’ Bajang Bregenjengan, who now claimed compensation for the interruption suffered. Which compensation? A basket of simile phalluses made of plated coconut leaves, that should be offered her by the river, near her usual place of residence –and love making. It was done as requested… Since those days, the children of Abian Gombal may disturb their parents in the act, but never the beautiful Bajang Bregenjengan. Anyway, they don’t cry anymore, meaning that the ‘goddess’ has no need for fake phalluses anymore.

All of the above has indeed nothing to do with swinging parties, genetic manipulation, Goethe’s romantic ‘Sorrows of Young Werther’ or other Western oddities. Sexual aspects of life is definitely more varied than what most of you think, isn’t it?