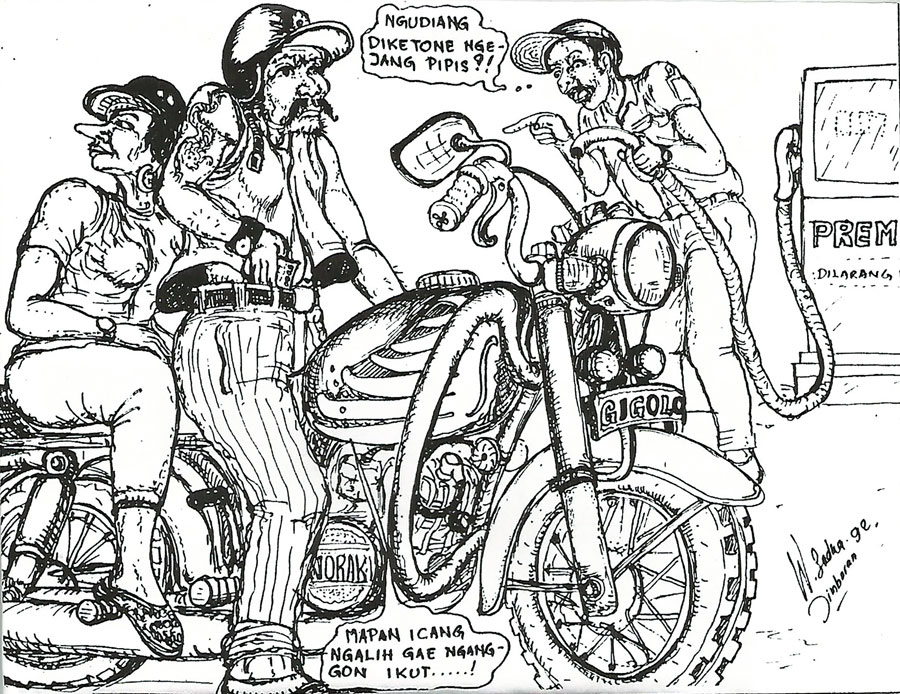

When he pulled up next to me, riding his big BMW bike, I immediately knew he was a beach boy, a “Kuta cowboy”, as we say here. His long hair was red from too much sun and salt. He was broad-shouldered, darkly handsome and looked straight into your eyes in an almost provocative way, very unlike ordinary, shy, Balinese youths. He was filling up his tank at the small roadside kiosk where I myself was buying fuel. It was time for him to pay.

“Twenty thousand,” I overheard the kiosk -keeper say.

Instead of digging into his pocket, the youth went deep down into his pants, between belly and zippers, and fumbling giddily around the place, he came out with a couple of rumpled banknotes. Then he looked across at me with a broad smile on his face and winked. I was flabbergasted. I knew men had ‘pouches’ there indeed, but I did not know these were full of money. But it did not end there. As he was paying for his petrol, the youth gave me another triumphant wink and blurted out: “This is where I get my money from, you see.” Then he left quickly with a roar of laughter pealing above the purr of his big BMW bike.

A gigolo!

Balinese gigolos come in several varieties. Most are found among the crowd of idle school dropouts, surf champions and disco freaks. Kuta-grown, they are usually after the quick shot and the fast buck. Plenty of sport and little romance! Once in a while, though, one of them comes to dream of the ‘lights of the city’ with a girl bewitched by the ‘tropical sun and coconuts.’ Before long they are married. The boy will turn long-shoremen in Sydney unless the girl becomes a bar owner in Kuta. Modern banality.

More interesting are the ‘cultural’ gigolos. A Balinese specialty. Impossible to miss them, ladies, if you haunt the high spots of Ubud life. Dressed in sarongs, a slack shirt on and friendly looking they stand out in the crowd: they have style and speak English too well for their environment.

Their world is the ‘real’ Bali. They provide lonely souls with a short cut to the discovery of the island. They will find you a princely cremation and know when Jimat is performing his next topeng dance. Should you need a dance costume or a master painting, they will eagerly fill your request. The night will just be the icing on the cake. You won’t feel the trick; you will just feel love. And your gigolo, Balinese prince or Sumatran painter, will be a dream lover, ready to do for you all you want him to do, even a few things you may have forgotten about.

The purpose of these gigolos is to create a bond, enmeshing sex, love and money. Most want the relationship to last: they have, after all, a family to sustain. Others may be raising capital for some business venture.

Once trapped, the chance is that you will wilfully contribute. From expensive restaurants to overpriced statues, you will pay everything. Later, back home, you will send checks and long to come back as a loved customer and cultural amateur. If you are tenacious, you will indeed come back, and may feel accepted: everyone will say hello to you in the streets. The laugh will come later.

What about your gigolo? He tries to run the show without mishap. To him, the most difficult is to somehow, juggle you, the dancer from the States, his wife from Ubud, and possibly the woman painter from Japan, who lives just beyond the river. Time-sharing. Be patient and discover the mysteries of Bali. Good luck. You may even marry.

Do gigolos bring about better inter-cultural understanding? One wonders. The Balinese sometimes complain that their Caucasian partners are ‘jelly-like’ (benyek) and complicated, while the latter say that the locals are ‘quickies’ and machos. These judgments lack sophistication, to say the least. If cultures cannot begin to understand each in intimate settings, where else can you begin?

Jean Couteau