The atmosphere was not a happy one in Pan Koncrong’s house. His daughter was lying in bed, feverish. An old medicine man (balian) had come and muttered a few magical words. But now he was gone, and neither his prayers to the gods, nor his potions were working. The child was lying helpless on the couch.

In a panic, Men Koncrong took hold of her husband’s arm, and stiffening herself an instant, she blurted out: “Oh, Jero Gede, Yen pianak tiange seger, titiang mesesaudan lakar ngotonin tur ngupah wayang” (“Oh Jero Gede (tutelary deity), if my child is saved, I promise to make her a proper otonon (anniversary) and to present you with a wayang performance).

Then, they waited, and waited. The night came. By early morning, signs of improvement were there; the baby opened her eyes. After two weeks she was again crawling on the ground of the family’s large bale (pavilion). Jero Gede had bestowed health to the sick child. But he had been promised a wayang (puppet show) performance and would be waiting for it.

Pan Koncrong and Men Koncrong soon forgot about their vow, (sot or sauh, “slip”) although the little girl grew normally, she was never quite healthy. Then the mother fell ill, and in just a few days, died of a bad case of diarrhea. She soon became “water” (meraga yeh), as people say, meaning that she was one of the origins of the holy water and she belonged “there,” a deified ancestor in the realm of the invisible world (niskala).

Meanwhile, in the realm of the visible world (sekala), her daughter, Ni Luh Koncrong, grew into an attractive girl. She was all the time sick, though, which worried her father. He decided, thus, to consult the gods (nunas baos) through a famous medium (balian mepeluasan). Tape recorder in hand, Koncrong, his new wife in tow — he had remarried in between — took his turn in the crowded line, and when his time came, sat as he ought to sit, presented his offering and waited.

By then the middle-aged balian, was by then shaking, and he talked, or rather, she talked, as it was the talk of the dead mother “Kene cening, dugas meme nu hidup taen mesesangi, yen nyak cening rahayu, meme lakar ngotonin tur ngupah wayang. Sakewala sing katutugan baan meme sawireh enggalang meme mati. “Which translates: “Oh my daughter, when I was still alive and you were sick, I promised that, if you survived, I would offer you an otonan (aniversary ritual) and present a wayang performance to Jero Gede”. The medium stopped shaking. It was finished.

Back home, the family gathered, around the tape. It was undoubtedly Men Koncrong’s voice. She was asking for her vow to be kept (naur sot ). A big otonan ceremony should be held, and a wayang show performed. Only then would things be back in order.

Some time later…

The day had finally come when Pan Koncrong and Ni Luh Koncrong would fulfil the vow, and the atmosphere was festive in the family compound. The youth of the neighborhood had all come and they were now playing ceki(cards) on a nearby wooden platform while getting high on arak palm-alcohol.

The women, meanwhile, were busying themselves with the preparation of offerings. The priest of the village temple (mangku adat) and the priest of the kinship temple (mangku panti), had been requested to lead the ceremony, and one could recognize them by their white cloth and headdress among the assembled family. Men Koncrong had long been cremated and she was now a deified ancestor “in the form of water,” (meraga yeh), as the tradition puts it. She nevertheless had to be kept “informed” of the proceedings and made to witness them (mesaksi). So the day before the ceremony proper, Pan Koncrong and his daughter, accompanied by a priest and family members had been to the cemetery and presented an offering to her soul and to the Lord of the dead. Men Koncrong would thus “attend” the otonan (anniversary) of her daughter and witness the fulfillment of her vow. Five chickens had also been slaughtered and would be offered to the Kanda Empat, the so-called Little-Brothers, born with the newly-born child in the shape of the after-birth, and who protect it throughout the phases of life as its cosmic guardians.

When the family members were settled in front of the offerings, Pan Koncrong and Luh Kerti in the first row, facing the “North” (Kaja), the village temple priest requested silence. He held between his fingers long slices of coconut leaves on which one could see a long line of Balinese characters. He read it, thus announcing the payment of the promise (naur sot), or in other words, the fulfillment of the vow, which would appease the dead and, thus, guarantee the living a more stable and happier life. He then asked whether the family was ready to “welcome” the soul of the dead. In other words, he proposed a “trance”. Quickly, perhaps wary of the unforeseen consequences, Pan Koncrong repelled the offer, and thus, Men Koncrong’s soul remained in her invisible Niskala abode. Then everyone was presented with holy water.

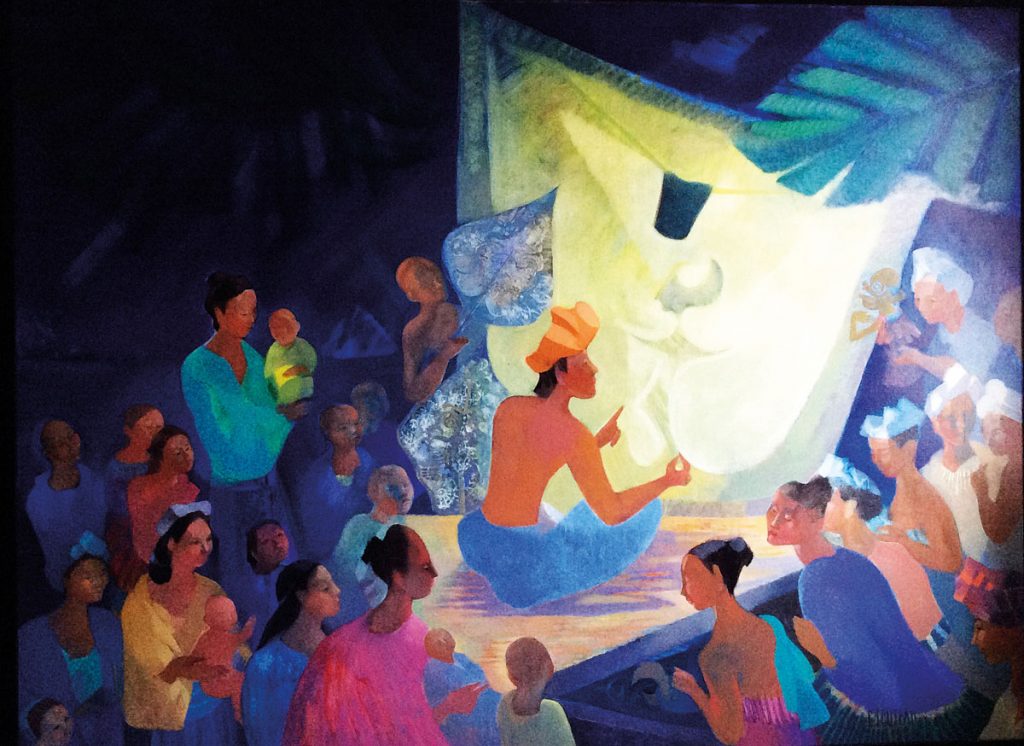

A wayang kulit performance had also been promised, and, with the approach of the night, the dalang came, a young man from Banjar. As befits a wayang performance from Northern Bali, everything was quick, fun, and dynamic. The show lasted barely two hours, and everyone laughed at the comic characters of Twalen and Sangut, who, unlike in the South, are attributed a moving jaw’.

Contrary to what might be expected, the story itself did not bear any relation to the paying of a promise or the condition in the world of the dead souls. It was just a regular love story, with the young male hero tricked by a giant and his pretty daughter.

Nevertheless, the show was part of a ritual. The puppeteer, called “Master Puppeteer,” or Jero Dalang, didn’t perform only as a show man, but also as a priest. Upon completion of the performance, a small ceremony was held, which produced a holy water called “Tirta Wayang,” which was then sprinkled around to the assembled family.

The following morning, Pan Koncrong, his daughter Luh Kerti and the whole family went one last time to the temple of the dead to send back Men Koncrong’s soul to her godly abode. She had indeed attended the whole ceremony, albeit in her invisible form.