It is a mistake to think that only bearded men with gleaming eyes seek ‘paradise’ by blowing themselves up in the middle of a crowd. Like it or not, Bali too has its own traditions of horror-inspired paradise seekers. Let us give it a look.

Widows’ Sacrifice

The most famous of these traditions relates to women: the sacrifice of a widow. Is it a proof of a deep and lasting Indian influence? Probably. In any case, the name of the ‘ritual’, mesatia (from satia, faithful) has the same origin as the Indian sutee. It is the paroxysm of an old obsession: women must be ‘pure’, i.e. virgin, when they marry and faithful when they are married. So, why not faithful down to death? The last documented mesatia was in 1904.

Ever concerned about the image of their island, modern intellectuals dispose of the issue in their own very Balinese way: “The kings often had a hundred concubines,” one of them told me. “Rather than surviving and being unavoidably accused of being witches (leak), and thus leading a miserable live, most princely widows naturally chose to sacrifice themselves. At least by jumping into the burning cremation pyre guaranteed them eternal bliss — their soul followed that of their lord and was sent ‘up there’ too, above the holy mountain. If a still pretty widow refused, she was usually forbidden to remarry. Infringing this taboo by taking a lover entailed punishment of death. Not infringing it entailed suspicion. Thus no bliss expected. As for the older widows, they were leak witches any way.”

In any case, the ‘show’ must have been quite a sight to behold. Let’s quote Dubois, a Belgian witness from the early 19th century, describing the way the women threw themselves from their platform: “She again performs the ritual gestures… her father lends her his kris, with which she wounds her arms and shoulders. She draws blood from the tip of the kris from the wounds she has inflicted and uses the blood to redden her foreheads.. She indicates in this way… that she has no fear of death.. She joins her own voice to the pious chants that she hears around her… She arrives at the deadly end of the plank…returns the kris to her father and, crossing her hands on her breast, jumps to the right, is seen for a moment in the air, and is engulfed in the glowing ember… A dozen men, armed with bundles of firewood and long bamboo impregnated with oil, throw them and pile them on top of her.”

Dubois’ depiction of a second death-seeking widow is even more horrendous: “She leaves her relatives… from her father she receives the kris with which she stabs herself downward from above her left shoulder; then she collapses and her father with her brothers lift her up to throw her, quivering, into the fire. No sign of fear or repugnance is visible at all on people’s faces”, says Dubois.

Puputan: Fight to the Death

Like in Islam, like in Shintoist Japan, suicide is thus construed as one of the ways to access paradise.

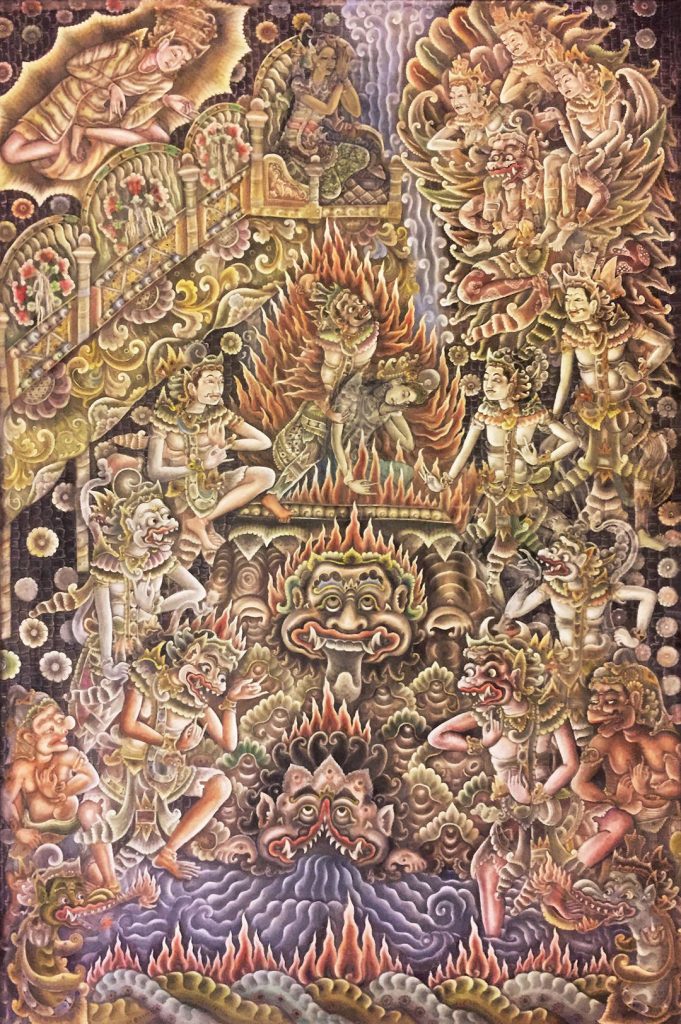

One finds it again, in the tradition of the puputan “fights to the death”. Here the Indian influence is irrefutable. The texts talk of dharma satria, warrior’s duty, and rena yadnya, ritual of war. The satria or warrior is duty-bound to defend his birthplace and country, and to die at war is considered the best way to head for what is called “Indra’s paradise”. In pre-colonial Bali, wars were often mere skirmishes, but in some instances, a princely family would fight to the death, their combat thus becoming a virtual suicide. The best-known pre-colonial puputan was that of Mengwi in 1891, which eradicated the kingdom of Mengwi, previously the most powerful of Central and Western Bali…Yet, Westerners know better the two puputan of Badung in 1906 and of Klungkung in 1908. In those puputan, the purpose of the Balinese fighter, accompanied by gongs and gamelan, and supported by the mejaya-jaya prayers of the Brahmins, was not to win, but to die and thus reach Indra’s heaven. To the Westerner who asks why the Balinese threw themselves fearlessly onto their rifle-armed Dutch enemies, and why they stabbed their wounded fellow-countrymen, the Balinese intellectual replies: “So that all would go to Indra’s heaven; so that no one would survive in shame”.

Other Suicides

Instead of helping one achieving heavenly bliss in Indra’s heaven, other types of suicide have the opposite effect. They contravene the path written for their life. Like the Balinese say: “people who kill themselves present themselves to Suratma, the guardian of hell, before their time is due. For this reason, they may not be cremated immediately. Their soul has to wait for three years buried in a special part of the cemetery, and be entrusted to the goddess of death, Durga, and to Mother Earth herself, Pertiwi. During this time, the soul is supposed to be tortured in the ‘field of sorrow’ (tegal penyangsaran), i.e. in hell. Of course, this does not go without its own series of rites. The most important, prior to the burial, is the ‘pengulapan’ or calling up of the soul. The latter is ‘deemed’ puzzled. It is still there, in the place where the suicide took place. Thus it has to be symbolically ‘called’ up to be settled in a set of offerings. Thus appeased, it will not bring havoc to the family and to the place where the suicide took place. The phenomenon of ‘atma kesasar’ or roving spirits is indeed what the Balinese fear most. In this context, the way usually chosen is to contact the forces of the niskala/intangible world through the intercession of a balian (shaman or medium). One always does it a few days after a death. When it is a suicide, the rumble-tumble and shrieks from the ‘world over there’ (kedituan) is often unbearable. But the balian will eventually come with a solution. If you kill yourself, it is not for some very obvious reason – despair out of poverty, illness or a broken live— it is most probably because you have neglected some duty toward your ancestors. It will behoove your grieving family members to appease them with offerings.

And sometimes the ancestors don’t forgive. There was the case of a handsome boy, twenty years ago, who fell in love with a Catholic beauty. When you are Catholic, you don’t change religion simply for the pleasures of marriage, you tell your partner to adopt Catholicism. Blinded by his love, the boy, an Anak Agung (high caste), consented to do it. And he became a genuine Catholic, going to mass and the like. Several months later, just before the day of marriage, his fiancée, following a quarrel, went to some disco with a former boyfriend. So, what did Agung do? He swallowed pesticide. And passed away of course. This time, the ancestors’ betrayal was not a story concocted by a balian, it was a genuine betrayal. Agung went nuts.

All this is telling us that, if you kill yourself, better do it for the gods and the king, or God and Country, if you prefer… At least, it is what the ancestors are supposed to think.