I can vaguely remember the way the policemen blocked the access to Kuta in 2002. There’s been a bombing, they said. Whilst I remember the day, my memory is nothing compared to those directly impacted, or even indirectly, by the events of that fateful day.

Once a year, on 12 October, they commemorate the tragedy that killed 202 people at Ground Zero, a monument built at the ‘scene of the crime’. The first Bali bomb is an event that is etched into their lives, a memory that lasts forever. Perhaps its effects can be seen as scars on their bodies, or are invisible as trauma affecting the very way they live. Some suffer from post-traumatic stress, still jumping when they hear loud sounds, explosions on the television or the loud ring of a phone.

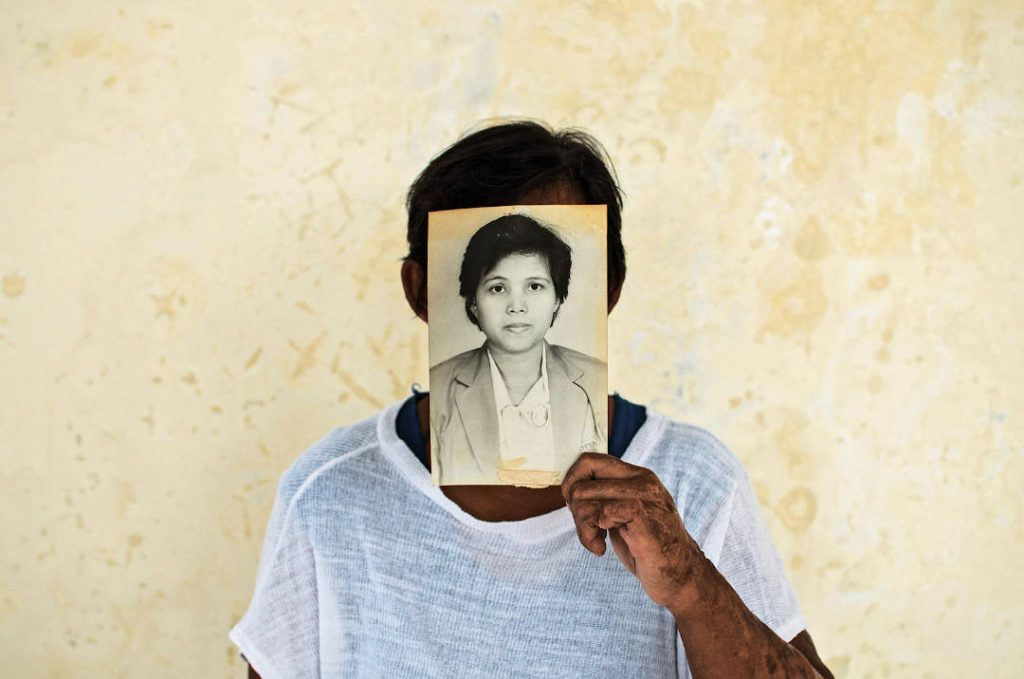

“My religion doesn’t teach hatred.”

These are the words of Ngesti Puji Rahayu, known as Yayuk amongst friends, a survivor of the bombs.

Her words reverberated in my mind. She suffered severe wounds to her body, yet she continued to smile.

Ngesti Puji Rahayu (Yayuk), one of the many 2022 Bali Bomb survivors, was born in Jember, East Java in 1962. During the Bali Bombing tragedy in 2002 she was at Paddy’s Club with her friends. She got injured in her face, left hand and almost of her body and being operated in Australia with a help from YKIP Foundation (Yayasan Kemanusiaan Ibu Pertiwi).

I created her portrait as part of a photography workshop by John Stanmeyer. I met with Bali bombing victims and they opened my eyes to the many problems experienced by survivors of the bombing. They suffered trauma, their wounds continued to give them health problems. So much so that they actually needed a government-funded trauma centre.

On the night of the attack of Paddy’s Club she was with her friends having a good time. But the good time turned into horror when the bomb exploded and her body was blown several meters before landing near the DJ booth. She passed out for a while, and when she woke up she saw piles of bodies and heard a voice shouting “Hot! Hot!”

Photo by Anggara Mahendra

Yayuk was sent to an intensive care unit in a hospital and she was thought to have died because of the severity of her wounds. She was already being sent to the morgue to be cleaned. Fortunately, she woke up and a foundation, Yayasan Kemanusiaan Ibu Pertiwi (YKIP), flew her to Australia to receive full-body surgery.

After her first operation in 2002, she was not allowed to expose her skin to direct sunlight, as it had lost its protective later. It itches when she is in the sun for too long.

In 2003, Yayuk received more treatment at the Royal Perth Hospital in Australia for her ears. In 2009, she underwent further surgery because keloids grew on her burned skin, which limited her movement. Afterward, she had several more operations, mostly to reduce the keloids that kept growing.

Yayuk is a strong woman, one of many survivors who have live their lives with reminders of the tragedy. Her reminders are physical and visible. She is our reminder of that tragic day, but with her words, “My religion doesn’t teach hatred,” she is also our reminder to always seek for peace and tolerance.

Lest we forget.