Journalist Eric Buvelot and socio-ethnologist Jean Couteau have recorded 20 hours of discussion about changes that have happened in Bali since the 70’s. The conversation was structured and segmented according to many different aspects of Balinese life, mostly from a socio-historical perspective, to trace all the overturning in Balinese mores since 50 years, when modernity started to shape new behaviours.

At the core of these changes, the birth of individuality in a communal society and the revolution it implies. The resulting changes have been more significant in 50 years than the ones happening during the previous millennium. At the end of this project, a 16 chapter discussion book will be published with the purpose of measuring to which extent Bali has morphed in so little time, a work never done before, encompassing all Balinese social matters. The French edition is due at the end of 2020 at Editions GOPE. The English one will follow next year. This month, we take a look with them at the mutation observed in Balinese art…

E B: Bali is today one of the centres of Indonesian contemporary art. Can you tell us why?

J C: Traditional art rests basically on a graphic representation of scenes taken from the world of theatre, in particular the wayang (puppet show theatre). This had a clear function: the objective of Balinese visual arts is to keep Balinese collective cultural memory alive. In other words it was a way to ‘teach’ the episodes of the great epics like the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, or the wandering of the hero Panji. The iconography was borrowed from the puppet show, which told the same stories. One finds good example in the Kamasan style. But beginning in the 1920s, a transformation started. Even though the aesthetics did not change much, painting continued telling ‘stories’ in a narrative, highly patterned way, in a space fully occupied, but instead of myth, it started telling stories of natural and village life.

E B: What spurred such modernisation of the visual arts?

J C : The arrival of westerners like Walter Spies and Rudolf Bonnet, who brought new techniques andintroduced questioning into culture, and in particular, into the field of visual representation. Previously, in Bali, every type of expression was tightly patterned –be it in theatre, music, dance, and of course the visual arts. Everything was coded and rested on recurrent motifs, be it visual, sound or gesture-related. Later, alongside the development of education in the 1950, followed by the multiplication of contacts with the outside world in the 1970, many artists started giving up not only ‘narrative figuration’ and patterning, but figuration altogether. Why? They were intent on expressing in new symbolic forms that was being ‘pushed’ into their mind by education, that is to say Hinduism. How? At the same time as Balinese intellectuals were restructuring Balinese religious tradition from an ancestors’ cult into full-fledged Hinduism, Balinese modern artist were expressing this transformation into abstract works: the complementarity of opposites, the Hindu trinity, and the cosmic wheel. These notions from modern ‘cosmicised’ Hinduism entered the visual arts at the same time as they were entering formal religion through the Hindu Affairs Council (Parisada Hindu Dharma). It is no accident that it is at that time, the 1970-1980s, was when the artists that have since made a name for themselves in contemporary art appeared.

E B: What does this reveal?

J C: It affirms modernity, with ‘Balineseness’ inside this modernity. But now, a new turn is coming up: we are witnessing a questioning of the modern world, as a consequence of globalisation. Yes, amazingly, as a reaction to the fact that Bali is ‘globally’ marketed as “paradise”, some circles feel that Bali has to play a role in establishing a new, global consciousness. This is most visible among artists, where the theme of ecology appeared very quickly. In 1990, Made Wianta already used a car in one of his installations. At the very end of the millennium, thus to welcome the year 2000, he set up a huge performance on the beach of Sanur by spreading a two thousand metre-long piece of cloth on which was written the word peace in all the languages of the world. More recently, this ‘internationalist’ spirit was broadened to new fields: the Balinese Nyepi[1] day of silence is thus promoted as a day of silence for the whole world, and the traditional Tri Hita Karana[2] system of ecological balance is being promoted as a solution for the planet’s environmental problem. Bali as guru of the world!

E B: Is there a contemporary art in Bali outside ‘Balineseness’?

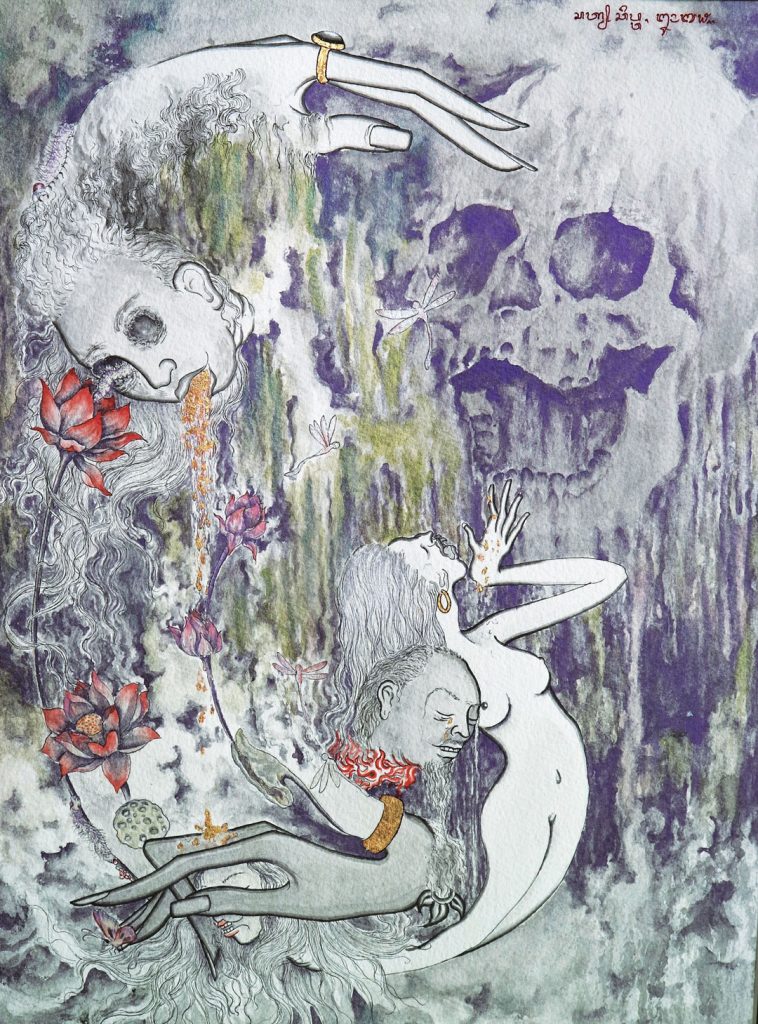

J C: Until recently, Made Wianta was the only one. But new generations are coming up. Mangu Putra’s spirit is mainly social and nationalist, from a Balinese perspective. Yet, most tend to express theirBalineseness thematically, using a modern/contemporary language. I am thinking here of Made Bayakwith regard to the Reklamasi[3]. Yet, most interesting is an artist like Satya Cipta, who is treating her ‘woman’s revolt’ theme in a fascinating Balinese visual language, shocking to most ‘traditional’ Balinese, though.

E B: So… aside from Made Wianta, there are no contemporary artists without “Balineseness”?

J C: There are several isolated cases. Most of them educated and sometimes living out of Bali. The most famous are undoubtedly Nyoman Nuarta, the sculptor of Garuda Wisnu’s fame, and the painter Nyoman Masriadi, who was the first Indonesian artist to deal with the new modernity- the bling-bling media-driven modernity. He ridiculed people using handphones, more than 15 years ago. On the other side there is Putu Wirantawan who paints extraordinarily surrealistic, even though abstract, ‘cosmological’ environments, but without any direct Balinese iconographic reference. Yet, in his style, in the minuteness of his lines, there is a strong Balinese touch. In a different way, Wayan Karja’s paintings of cosmic emptiness also feature the Balinese notion of Embang, the void. Thus, on the whole there is no refusal of Balineseness. But one finds it now in a most universal form.

E B: What about Balinese cultural memory? Are we seeing the end of it?

J C: To a certain extent, yes! And I think that it is the most important transformation that has taken place since 700 years, i.e. since the Majapahit invasion from Java in 1343! This transformation is spurred by momentous economics, and ecological mutations. There is an ongoing shift from the Balinese language toward Indonesian and even toward English. Then ensues a transformation of the way of thinking: from symbolic-narrative and, local, it becomes normative, logical and trans-national. This translates into the creation of norms, vague first, then more and more structured, in virtually all walks of life.

E B: To conclude, are theatre and dance shows less frequent today?

J C: Outside tourist shows, it is undeniable. Balinese theatre, which was basically a rite, is increasingly turning into a mere show. In the past, a theatre performance was called upon whenever there was a significant event such as a birth, a temple festival etc. For example, when a child was born, or if one fell ill, one would make a vow: “if I am healed, or if my child grows up in good health, I will offer a wayang kulit to the gods.” Such habit to make oath is slowly waning. Sacred performances are accordingly less numerous than they were in the past. Sacrality is changing. It is moving away from offerings toward prayer, from gods to God, from orthopraxy to orthodoxy.

Note: Discussions

between Eric and Jean will be published every 2 months, interspersed with

Jean’s regular cultural column.

[1] The day of silence in the Balinese Saka calendar, which usually falls in March. This year it falls on March 25th.

[2] This so-called basic principle of Balinese philosophy identifies three causes of well-being: harmony between human beings, harmony between humans and nature, and harmony between humans and God.

[3] Dubai-style tourism reclamation that has been opposed by most Balinese for many years.