Cultural regeneration is an essential aspect of Balinese painting, with techniques and knowledge of narratives passed down through the generations. However the woman’s role, especially the daughters of artists, has yet to be acknowledged.

“It was very unusual for a woman to occupy herself with art, and after I Desak Putu Lambon, it took thirty-five years before another woman established herself as a painter in Batuan. The reason for this does not lie in the lack of talent, but in the strict division of Balinese society into male and female areas of activity,” writes Klaus D. Hohn in ‘The Art of Bali – Reflections of Faith: The History of Painting in Batuan 1834-1994’.

I Desak Putu Lambon’s date of birth and passing are unclear. Born around 1923, she died between 1975 and 1979. Lambon is the first Balinese woman painter to be written about by researchers in the 20th century and the first known female Balinese artist of the Batuan village, with a technical style that has been critically acclaimed.

Lambon is the daughter of the celebrated Dewa Putu Kebes (1874-1962), a pioneer of the Batuan School of Painting. A gifted man, Kebes was an important community figure concerned with artistic and religious affairs. A talented woodcarver and outstanding mask maker, his statues and masks are still visible in the Batuan village temple today. Kebes occasionally sold his modern paintings to the growing tourist market to help support his family.

His daughter Lambon is the sole female painter featured in the iconic Bateson-Mead collection. American cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901-1978) and English anthropologist, social scientist and linguist Gregory Bateson (1904-1980) conducted landmark studies on the mindset of the Batuan people by researching their responses to dreams. They commissioned over 2000 paintings from the artists, and Bateson purchased ten of Lambon’s drawings, all dated 1937. Lambon was about fifteen years old at the time of Bateson and Mead’s research.

The images created by the Batuan painters are in a pictorial language that is not Balinese. The paintings were not beautiful stylised compositions made for the tourist market. Yet, the works expressed matters of deep concern to the people. American anthropologist Dr Hildred Geertz in her 1994 book ‘Images of Power: Balinese paintings made for Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead’, makes the defining statement on the Bataun works collected by Bateson and Mead.

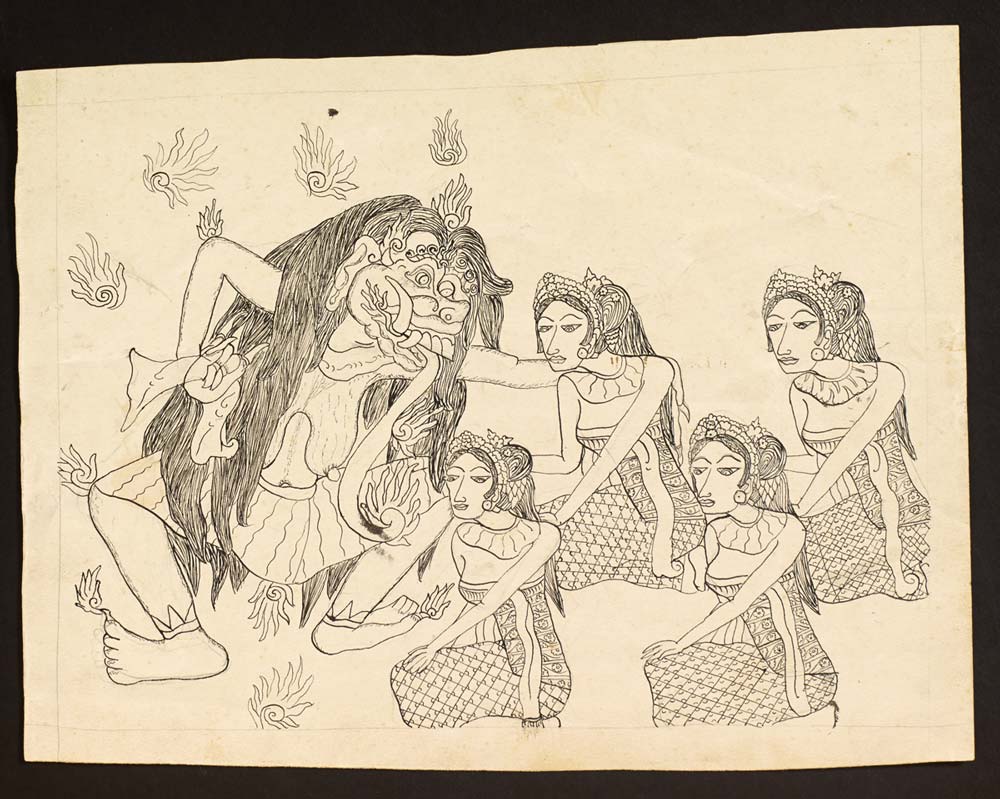

“The Batuan painters seldom portrayed worlds of light and harmony and laughter, or the external world of mere appearances. Rather they grappled with those forces that, for them, are concealed under the surface of things, the real world of dangerous, invisible supernatural beings and powers. Since in Bali one of the main ways of speaking about such matters is through telling stories, many of the pictures are formulated through narratives drawn from folktales, shadow puppet shows, and the popular dance dramas. And many pictures went further, portraying sorcerers, demons and malevolent spirits. If they can be taken as individual statements, these pictures reveal a great deal not only about the inner preoccupations of the makers, but also about their fundamental notions of the universe.”

Geertz also makes this insightful comment, “To call the spiritual beings who visit the human world during a temple festival “gods” and “demons”, as we must when we write in English, seriously falsifies Balinese ideas about them, since it implies each one is either consistently “benevolent” or “malevolent”. Any so called god or demon of Bali is capable of being both helpful and harmful to people.” And, “A major impediment in Western understanding of Balinese thought is the long and pervasive Christian tradition that defines “religion” as central and serious and “magic” as peripheral and trivial.”

Lambon attended school for three years, despite her family being poor. She could read and write Malay and learned the Batuan painting style from her father. Kebes asked another pioneering Batuan painter, Nyoman Ngendon (1903-1945), to teach his daughter to paint.

Lambon was a friend of Ida Bagus Ketut Togog (1913-1989) the ritual art specialist who was one of the leading painters in Batuan. It is probable Togog was helpful to her in learning the Batuan style. We can only speculate about how much Lambon participated in her father’s paintings. Daughters were tasked with stretching and priming canvases along with colouring in compositions. Around 1935, Kebes and his family moved to Sanur, then later Sibang and Klungkung. A few years later, when Kebes became ill, they returned to Batuan.

Professor of Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Sydney, Australia, Adrian Vickers, notes on the website BalinesePaintings.org, “Unlike many other artists of the time, Lambon was not influenced by Bonnet or Spies, but by Theo Meier, another European artist resident in Bali (Sanur). More accurately, she was influenced by working in the studio/household that Meier created, where artists from Sanur and Batuan met together. This gave her work a more naturalistic feel than that of Ngendon’s. Lambon’s work included collaboration with her father, Dewa Putu Kebes.”

Geertz writes of Lambon’s experience in Sanur and the influence of Theo Meier and his group, “Meier had considerable contempt for Spies and Bonnet, apparently a mutual feeling. Meier encouraged the painters he knew to stop putting ‘all those leaves’ in their pictures.” In 1939 when Mead returned to Batuan, she noted that Lambon was married and had stopped painting. Another report from the 1980s expressed that she continued to paint post-WWII.

Description of Paintings

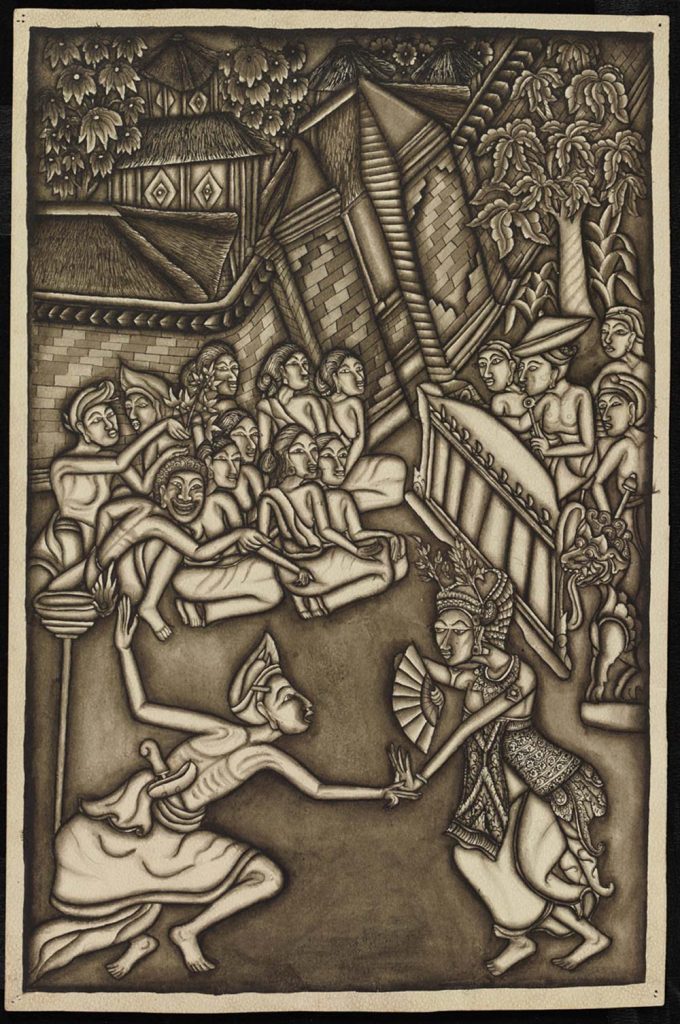

Photographs of Lambon’s paintings reveal a diversity of pictorial styles. Some of her monochrome images, Chinese ink on paper, describe simple forms, her figures are angular in structure. She adopts an economy of means, rendering only the necessary visual information without decorative backgrounds to express her narratives. The contrasting relationship of the negative space of the black background with Lambon’s icons emphasises the characteristics of her style.

Lambon’s September 30, 1937 ink on paper drawing ‘Discussing Preparations for a Dance-Drama Performance” is one of a number of line drawings, consisting of structural information and blank white spaces of paper, without the over detailed use of patterns and icons to fill the canvas space that categorised the Balinese works for the tourist market. Lambon does however place attention to detail in describing the brick work and other buildings, and the barong masks. Her style is described as being very naturalistic.