If you are a fanatic of Bali, you will be interested by the character of I Gusti Nyoman Darta. He had an early life typical of the feudal system of the days. Barely 5, he was entrusted by his father to one of the princes of Ubud, Tjokorde Ngurah Puri Saren.

He took the mantle as a “parekan”, let us say a young servant, but also much more, because if he gave a hand at the palace, he was also schooled by his lord, like many other boys and girls of the village. But, because he was gifted, he was also, with time, taught all the palace-related knowledge, down to its secrets: how to make a powerful barong mask, how to build a temple without disturbing the forces around it, and so on.

He passed then passed exams and became a teacher. He taught for twenty years, until, one day, he had a “visitor” from the ‘unseen’ world. Was it in his imagination, during a bout of fever, or as a dream, he does not know. But he was definitely visited by a voice, so he remembers, which asked him to follow and serve it. It was a lord from the niskala world out there. He had no other choice than to follow this lord. Since then, Darta has become a healer and an adviser to the Ubud village and to the local princely families in matters of festivals and palace ceremonies. He is often invited outside Bali to look after temples under the custody of the Ubud princes like the great temple of Mandala Giri, at the foot of the Semeru mountain in Java.

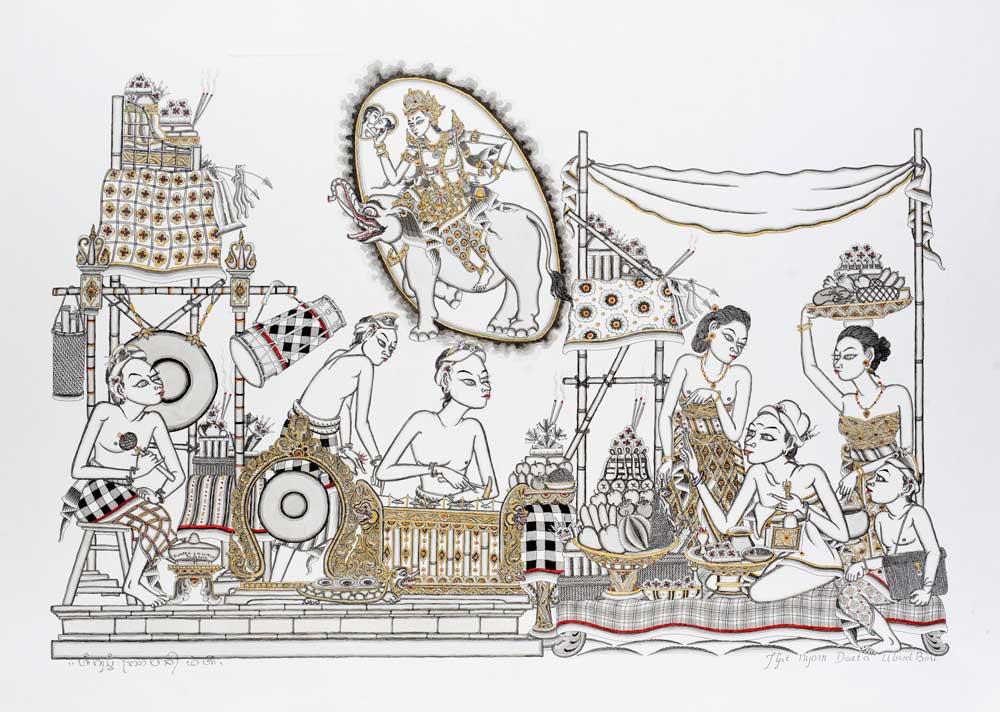

Yet, I Gusti Nyoman Darta is also known – in fact well-known beyond Bali — for his illustrations of the book “Time, Rites and Festivals” (2013), in which he revealed himself to be able to draw, in his own manner, in the style of Bali’s maestro I Gusti Nyoman Lempad (1862-1978).

Lempad is arguably Bali’s best visual artist. In the 1930s, probably under the visual influence of the German resident-artist Walter Spies, he revolutionised Balinese style by giving the drawing line full autonomy. Instead of being exclusively narrative and looking “broken”, like in old Balinese tradition, the line now existed for its own sake. Lempad thus invented Balinese ‘black and white’ drawing.

Lempad was I Gusti Nyoman Darta’s “grand-father” – an ancestor from the same clan. They shared the same clan rituals and, more importantly, they both were “palace men”, or parekan of the princely House of Ubud. While I Gusti Nyoman Darta was growing at the palace under Tjokorde Ngurah’s wing, he would often meet Lempad, who was visiting from his house nearby to take orders from a prince or simply to attend Balinese poetry reading or puppet show performances. So they became very close. Darta often witnessed how Lempad worked: “His line had no ending, he says.

Is it why Darta’s drawings share a drawing line that call to mind that of his famous “grand-father.” Not exactly. As he explains it, he did not study with the old man. He knew him and, living at the Ubud palace, he often accompanied the older man to his visits to the local prince. So he could to a certain extent partake in the very old man’s inspiration. But, Lempad, born in 1862, was too old to be able to properly teach his younger parent. He told him instead: “Just focus on what you are doing, learn the stories, you will certainly be able to be as good as me.”

Darta did so, in his own way. Magical. He had a photo of himself next to Lempad. Accompanied by meditation, this photo, he claims, enabled him to catch Lempad’s creative power, the old man’s taksu.

Strange, isn’t it? But Darta had a precedent. He says that he was inspired by Bambang Ekalaya, a hero of the wayang puppet-show theatre, who had learned his archery skills through a statue of his old teacher Drona.

This story is an a offshoot of the Mahabharata which is well-known to the Balinese puppet masters. It originates from Java, but was imported in Bali at an unknown time, probably in the last century. Let us tell the story in a few paragraphs.

As all wayang lovers know, Arjuna, the most handsome of the 5 Pandawa Mahabharata heroes, was also the best archery student of the great guru Begawan Drona — who will later side with the 5 brothers ‘enemies, the Korawa, during the great and final Bharatayudha battle.

Bambang Ekalaya was a warrior of low social status. He was a good bowman, but wanted to be the best in the world. And to be the best, and be superior to Arjuna himself, he had to learn from the best teacher in the world, Begawan Drona. But when he came to ask Drona to be his teacher, the latter refused because of his lowly status and also because he had sworn that Arjuna would be the best archer ever.

Ekalaya was not to be spurned so easily. What mattered to him was to have Dorna’s power transmitted to him. So he went to the forest, where he made a replica statue of Dorna and behaved toward the statue with all the respect due to a teacher. As a result, extraordinarily, and unknown to Drona, he was bestowed the skills of the best teacher ever. Alas, Arjuna discovered that Bambang Ekalaya could shoot on target better than himself and complained to his teacher Drona. The latter, who had sworn to Arjuna that he would be the best archer ever, then devised a trick. He asked Bambang Ekalaya to demonstrate that he respected his teacher and was ready to obey all the latter’s requests. Bambang Ekalaya agreed to fulfill any of his teachers requests. Then Drona asked him to cut off his forefinger. Unruffled, Bambang Ekalaya immediately cut it, rendering his archery useless. Thus, he would not be the best archer ever, but the best disciple ever.

By calling up this story of Bambang Ekalaya, what Gusti Nyoman Darta is implicitly telling us is that talent is not so much something inborn through descent and part of one’s DNA, that something intangible, a magical power transmitted from one’s master through faithfulness, discipline and identification with him. He knew Lempad, served him as a kid whenever the older man went to the palace. So he could sufficiently identify with him to catch some of his taksu power — even though he did not cut his painting hand.

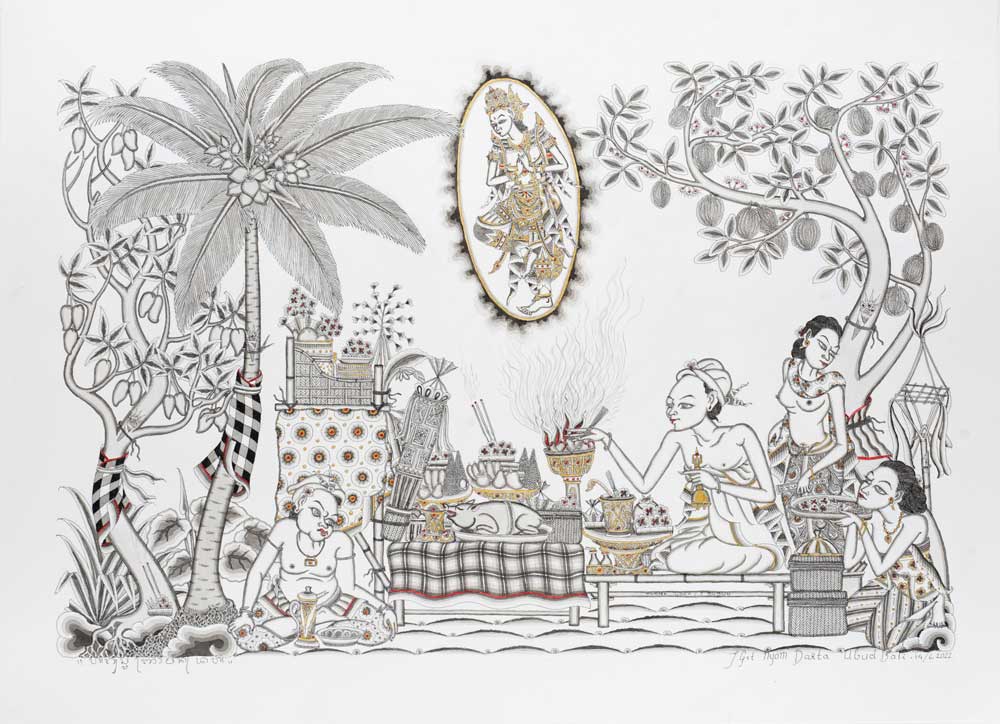

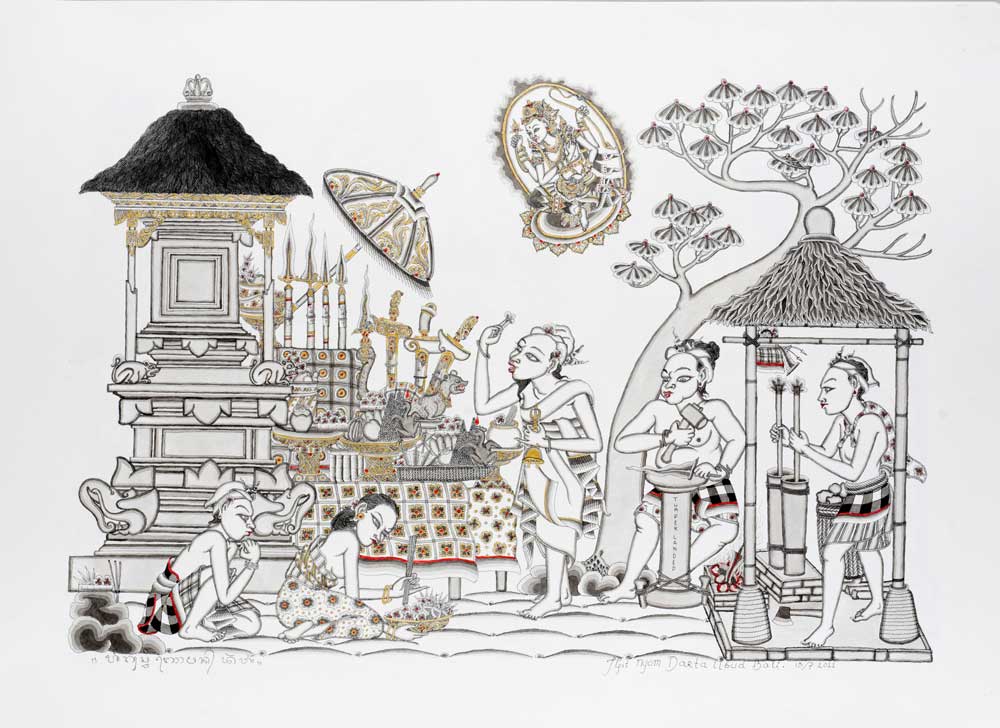

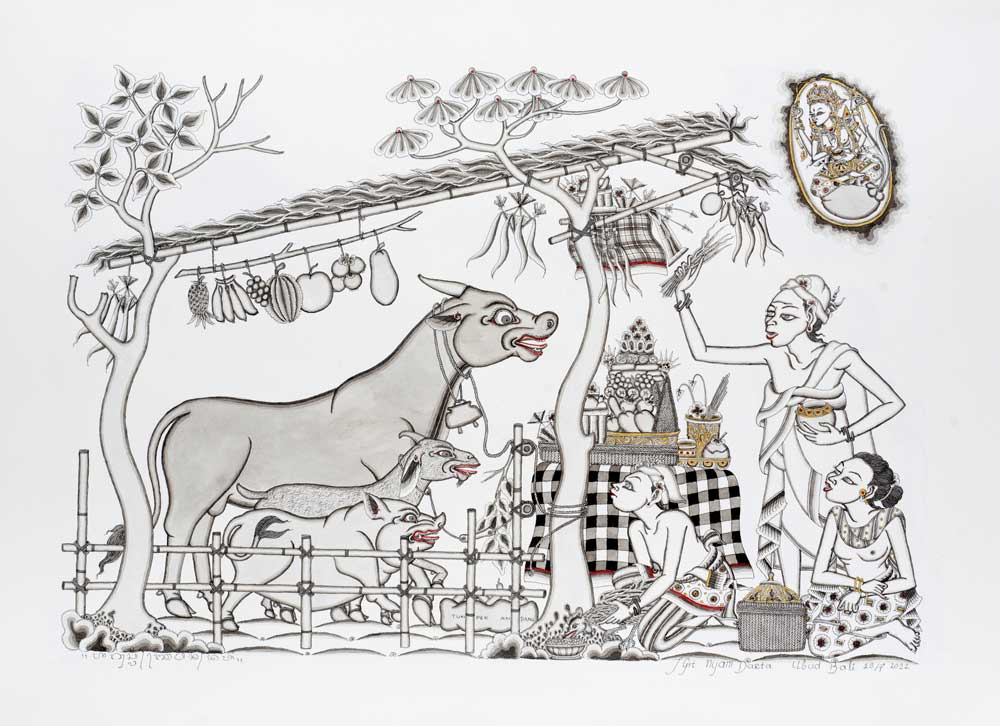

As for his drawings, here you will see some of his works. Drawings made to celebrate the day of the puppet show wayang theatre, tumpek wayang, and other ‘tumpek’ celebrations.