It may be interesting to the reader to see the way Islam first arrived in Bali. The reality of its arrival is a far cry from the overly dramatic prism through which today’s media tend to present relations between religions.

Islam did not arrive in Bali as a religion, or rather, when it arrived, it was not perceived as such. It arrived in the shape of individual traders and sailors, people who came ashore, one at a time, on the Northern coast of Bali and who, for one reason or another, settled there. They were not so different from the Balinese. They had their god, too, whom they claimed was the only one.

Of course their god was not one of the gods who dwelled on the mountains. He was not worshipped as Batara Tolangkir or Batara Batukaru. He was a god from far away, so far that no one really knew exactly where he was from. He did not request offerings, nor did he come down for visits, like Balinese gods. So he was not very demanding. Short prayers sufficed him, and he did not allow his penyungsung (worshippers) to eat pork. But otherwise nothing seemed out of the ordinary.

Thus, the North Balinese of the time, around the 14th century, had no reason to think that this newly introduced god was of a different nature. The newcomers said his words were kept in a holy book. Fine. But this book was not available. And, anyway, the Balinese had their holy books, too, the palm leaf lontars.

Thus, the Balinese had no reason not to welcome those outsiders. Some even gave them their daughter to marry. Over time these new settlers took root, one at a time, one here on the coast, another one further East, unconnected with one another.

Forty or fifty years later, when they passed away, their Balinese wife had no clue about what to do with their husband’s corpse. No true believer was there to explain how to make a tomb, oriented westward, in the direction of the holy city. The only thing their wife knew, as a Balinese, was that corpses have to be burned and ashes dispersed into the sea, so that the dead man’s soul can be released and go back to where it belongs, to the old world (tanah ane wayah) of the dead ancestors. So they did what they thought was best: they each turned their husband into an ancestor, a Batara, whom they could worship locally. And since, before passing away, those non-Balinese had said they came from the Mekkah of the East, Demak, they were all called the “ancestor from Mekkah.” In other words, the first Islam which came to Bali through those individuals mentioned above was effectively “swallowed” by Balinese religion post-mortem! Throughout Northern Bali, there are many temples with “ancestors from Mekkah.” During temple festivals, the story of the long ago arrival of those “Mekkah ancestors” is still performed to this day.

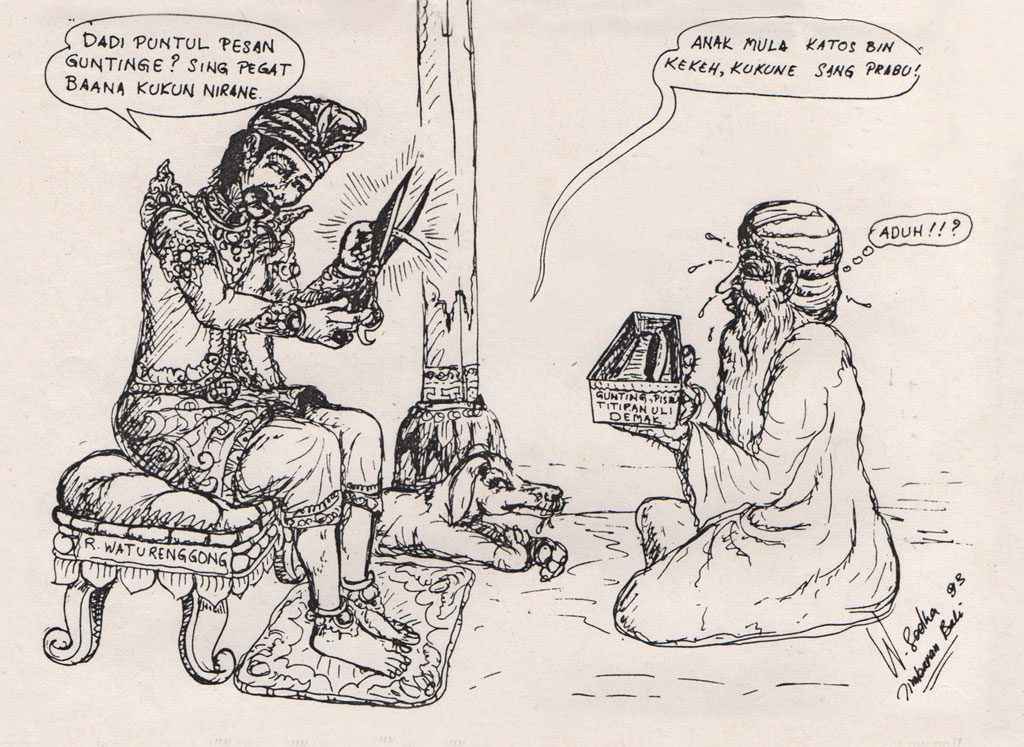

Two hundred years later, Islam had still not been taken up by this little island. It was instead prevented from taking over Bali by a decision of the local king. The way it occurred is depicted, not in a blunt factual way by a court chronicler, but in a metaphorical way, through a local folk story.

The king who ruled Bali in the 16th century, was reputed to be the greatest king of Balinese history, Waturenggong. His palace was then in Gelgel, near today’s Klungkung. His main threats came from the West, where the Sultan of Demak was steadfastly expanding the areas under his control. And with this control, came religion, Muslim clerks in tow. Typically the ruler of Demak would send an emissary to tell local rulers and kings to submit to the new faith and, hence to his rule, or else….

But it did not work as expected in Bali.

As the local story goes, when the Sultanate’s emissary presented himself to Waturenggong and asked the king to become Muslim, thus, ipso facto, a vassal of Demak, the king did not refuse right away. It would have been insulting. But he put forward a condition. The emissary should be able to cut the nail of the kind’s thumb (symbolic of circumcision!). Only then would the king, and Bali, become Muslim.

A priori it was not a difficult task. Muslim traders of the day had a monopoly of sorts on the import of blades into the archipelago. So the emissary took his own best blade and respectfully approached the “thumb” of the laughing king. He would do the job without problem. Or so he thought.

Except it did not work as he expected. His blade could shave his own chin every day, but it was impossible to cut the king’s “nail”. The blade just did not bite. And the king was laughing more and more. There was some magic at work here. The king was too sakti (sacred), too protected by some other worldly force!

Finally, exhausted, the emissary gave up. He was at his wits end, and also in quite a predicament. He had failed in his task. How would he be welcomed back in Demak? All the other emissaries sent to the East – Lombok, Ternate, Tidore – came back talking of enthusiastic acceptance of Islam. But his own mission had been a failure. He could not go back to Demak. He would lose face, and perhaps his life.

So he bowed in front of the king: “Oh Waturenggong the great, pardon my impudence in thinking that my blade would be stronger than you body. But I cannot go back to Demak. So please grant me your pardon and allow me to become one of your loyal subjects.” So it was asked, and so it was generously granted. The emissary and his following, it is reported in the local lore, settled among the Balinese. Their descendants are now found scattered in several Muslim hamlets in and around Klungkung.

History is interesting. On the other side of the world, when Paul was faced with the refusal of the local Greek people to have “more than simply their hair” cut off, he discarded the blade. It is how the West became Christian. This raises an important historical question. Without the test of the blade, would Bali have become Muslim?

In any case, once accepted by the kings, the Muslims were protected and welcomed ever since.