Balinese society, like all societies, show numerous features of gender inequality in rights, status or simply behaviour. One of the most persistent imbalances pertains to the perception of female sexuality as being basically “impure” (sebel).

Blood is associated in Balinese religion with negative forces, the butakalas. It is the main ingredient of the offerings addressed to demons to placate them. The tabuh rah, or slaughter of an animal, usually a chicken, is a prerequisite to many Balinese ceremonies – hence the cockfighting tradition. In regards to women, they are, on account of their blood, subjected to the onslaught of demonic forces during the whole length of their period. Least you think that I am full of prejudices, let me quote a well-known and highly respected book of wisdom in the writings about the women’s Vulva. It is no less than a “year-long incurable sore, which causes the world to go bananas.” (ritengahnikangkulitsasulpitningkidang, hana ta kani, menga ta kenengwaras …. Ya ta angdewulanguniriking rat, muda, wuta, tuliyadenya. Sarasmucaya 31:438). Of course, the word ‘banana’ is my translation. Menstruation is thus really every Balinese woman’s scourge, not only physically, but also socially, as we shall see below.

When a Balinese woman menstruates, she is said to be sebel di awak (dirty in the body). From that moment on, and during the whole length of her period, she has to abide by prohibitions and obligations, which are the many reminders of her “impurity.” She is barred in particular from all religious tasks and duties. Instead of going to the temple or participating in the collective preparation of offerings, she must remain at home.

Religious activities play a paramount role in Balinese social life, and non-attendance is always an embarrassment. To avoid it and compelled by fear of possible ostracism, some Balinese women go as far as trying to manipulate their period, and they have their own Balinese tricks to achieve it: for example sitting on a canang offering placed in a corner of the bale dangin (east pavilion). It is said that such canang can shift the period until after an upcoming festival or ceremony.

Some prohibitions apply to aspects of the woman’s daily life. In old-fashioned circles, menstruating women are kept outside of their sleeping quarters. They spend the time of their period in a small shed added to the bale dauh (Western pavilion). And there, they have to lie on the ground. They are not even allowed to sleep on a mat.

There is also no question of freely circulating in the compound. The northern pavilion (bale daja) located on the side of the godly, as well as the granary — (jineng), where Sri, the goddess of rice, is said to reside – remains out of bounds to them. Food has to remain pure too. When taking their meal, they have to be wary of which plate they use. There is also no question of sexual intercourse. As for their bathing, it is no easy matter either, nor is washing. While at the river, they have to keep an eye out to see if someone else is bathing “downstream,” and they must avoid at all cost of mixing their own dirty clothes with those of their family members.

In other words, whatever they do; sleep, eat, move or pray, menstruating Balinese women are constantly on their guard, lest they transmit their “impurity” to others.

Under these circumstances, one understands why there is a special ceremony upon the coming of age of a daughter: the menekbajang (or raja swala for upper caste girls). Its purpose is to placate her bodily demons. During this ritual, there is a moment which is of particular symbolic importance: the girl is made to “taste” some of her first blood. In other words, she ingests her own demons. By doing so, she gains the strength, in later years, to cope with other demons – those of her male partner.

It must be added that menstrual blood does not always entail negative consequences. It you can read the letter written (in French) by a Walloon sent to find soldiers for the Dutch government in 1828, you will read heart-wrenching stories about young women throwing themselves into a burning pyre to follow their husbands in death. It was known as the “mesatia” rite – the rite of faithfulness. But women who had their period were not allowed to sacrifice themselves. They would have besmirched the process of release for the dead man’s soul…

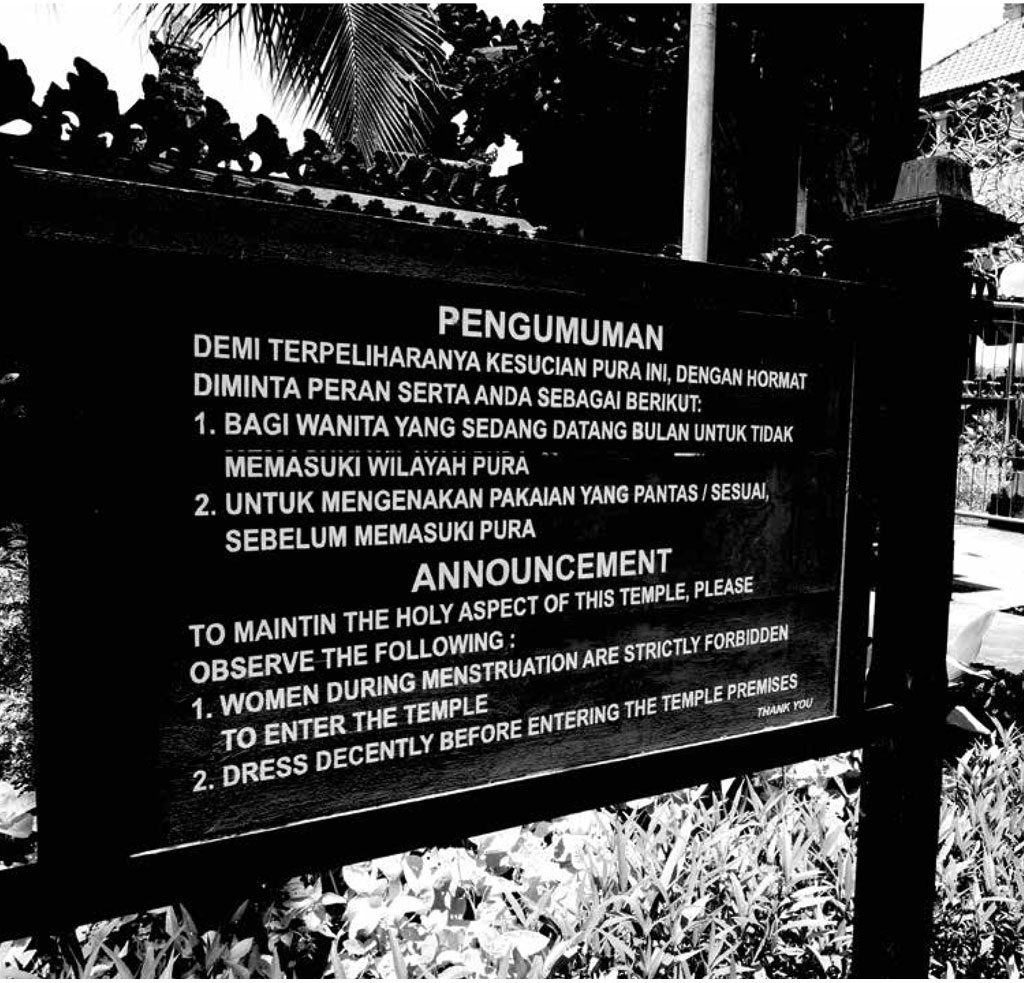

On a lighter note, perhaps you know that women tourists are not allowed to enter Balinese temples during their period. You will find a board at the entrance of many temples reminding them of this prohibition. But forty years ago, people did not speak good English, or their English was too good to be true. I still recall a board on which it was written: “It is forbidden to penetrate women during menstruation.” So, whatever the condition of women, not everything is lost.