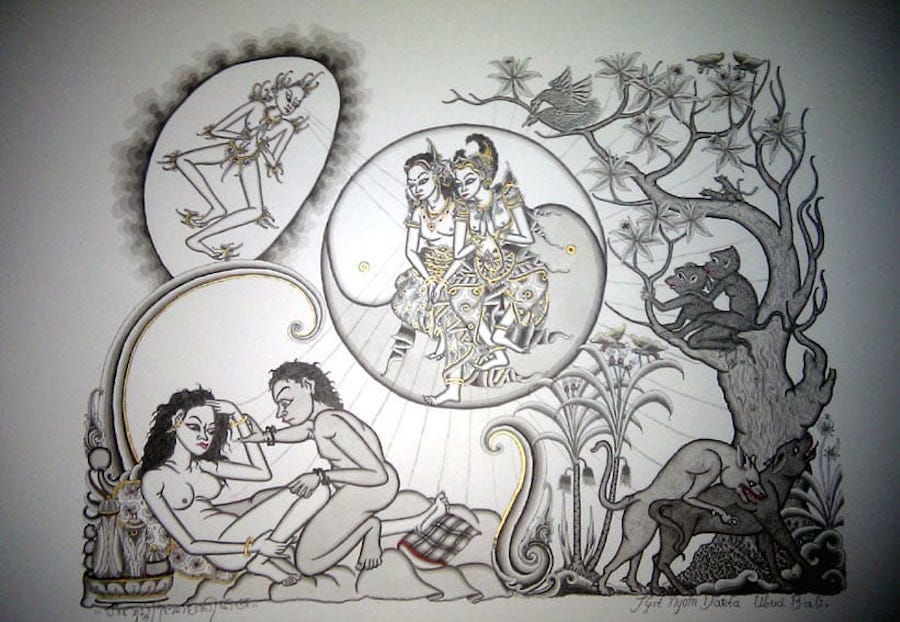

In Bali, love and indeed sex are more than just about the relationship between two people. It is about the gods, the cosmos, the cycle of life.

For most Westerners love oscillates between two poles: on one side there is the romantic meeting of two individuals, and on the other side, the sexual encounter of two natural opposites, the active spermatozoon and the passive ovule. Platonic love versus romantic, or in ‘eros’ versus ‘agape’: these are the irreconcilable opposites that have always haunted the Western and now the modern world, with all their related problems and anxieties.

Always original, the traditional Balinese look at love with different eyes. To them, eros (passionate love) and agape (unconditional love) are complements rather than opposites, and love is beyond the grasp of the individual.

To the Balinese, the sexual and love meeting is more than just an affair of two persons. It is a cosmic encounter. The person is thought to be a Microcosm (Bhwana Alit) that carries within the self a replica of the global cosmic forces (Bhwana Agung, or Macrocosm). Thus, love involves not only individual persons, but also the forces of the macrocosmic world.

Expressed in the medium of Balinese myth and philosophy, the love of a man and a women is an encounter of the god of love Smara (also called Kama), and the goddess of the moon Ratih or that of the cosmic male “Spirit” Purusa, and female “Matter” Pradana . Everything is eventually reduced to a system of sexual and complementary opposites (Rwabhineda ).

These conceptions are more than just symbolic images and people act accordingly. Magical illustrations of godly lovers are widely used by balian (shaman) to induce love in the intended partner.

Not all the ploys are magical, though: in some villages, if a man or woman is unable to find a mate, he or she might go to cosmic extremities: the man lies on his belly and implores Pertiwi – the mother earth goddess – to bestow a wife on him, while the woman lies on her back and addresses Akasa – the father sky god. The symbolic sexual union of the man or woman with a cosmic lover is thus thought to bring him or her a human partner. This is not without sexual connotations, though: the earth is always where it should be, underneath the sky.

Since love is beyond the individual, the forces that control it can easily be manipulated if need be. Balian witch doctors use a whole array of charms and counter-charms such as effigies of gods and demons, hair, rings etc. This magic has the advantage of taking the problems of love beyond the responsibility of the individuals: if your daughter sleeps with Made Kelor, it might be for the simple reason that he carries a powerful ring, which he must have got as a gift from a reputable temple.

One can also apply magic in breaking off undesirable relationships: if your daughter, of the best blood, falls in love with that scoundrel, Ketut Dollar of lower caste , there are ways out. You take her to a powerful balian and he will “catch” the lover’s spirit and cast it aways, regardless of what your daughter thinks. It is highly convenient, and it usually works, except when the tension runs so high that the youth chooses death instead by suicide.

To the traditional Balinese, love extends beyond the person’s life into the chain of its incarnations. To the sekala (tangible) love corresponds the niskala (invisible) one: you once met in the realm of spirits and now you meet in an earthly love. So, now your main purpose is to enable one or several souls – your children – to incarnate from the other world.

According to Balinese myths, sexual intercourse is made possible through the entreaties of the god, Sang Hyang Deleng, described as “the god of the love stare” (deleng). The rough translation of the”love stare” comes as the encounter of the two Kama emanations (the god of love): the white Kama , which is the sperm of the man, and the red Kama, which is the ovule of the women. Their union produces a foetus, called by another god’s name, Sang Hyang Jabang Bayi, that becomes the receptacle of the soul incarnating from the “Field of Sorrow” (Tegal Penyangsaran – or hell), where it was punished for sins from a past incarnation.

Once born, the soul has a debt, so people say, towards its begetters, whose sexual activities have made the incarnation possible, hence ending the tortures of hell. This debt is paid upon the parent’s death, when their soul is sent back by the children – through the various rituals of death – to its invisible niskala abode.

But in the meantime, the incarnated soul – the child – has to look after itself. It has to find a love partner, in order to have the children who will in turn prepare the rituals of the upcoming death. Thus, to the Balinese, finding a mate is not just a sexual game; it is every incarnated soul’s most important need, that may open the path to ultimate release, when the soul merges into the Supreme Soul (Paramatma – God).

A sacred duty, sex should therefore be controlled, by gods rather than by demons, as illustrated by the metatah coming-of age ceremony: the demonic forces are symbolically placated by the filing of the teeth, while the “patients” lie over drawn symbols of the participating gods, (Smara and Ratih).

After the metatah ceremony, the search may begin. The partner one selects has to be the right one. In Balinese stories, all the women the hero meets who are not thus “indebted” to him are “witches” driven by demonic desire. The debt may result from past encounters in the aforementioned “Field of Sorrow”. For example, if you had helped a female soul to walk across the infamous wobbling tree (titi ugal-agil) to escape from the advances of a lustful boar, you might well have unknowingly met the wife-or lover-of your next incarnation.

After the partner is found, Kama is satisfied. The time comes now to look for wealth, artha, which corresponds to the second phase of life, and thus, to provide a living for the children who will care for their parents’ souls after death. Later, in more advanced years, one should strive for virtue, dharma, and overcome all earthly desires. Sex should cease, as it is then the age for knowledge (aji). The soul is waiting for deliverance or moksa, ultimate enlightenment. If it succeeds, the soul will rejoin the ancestral abode, high over the mountains. If it fails, it will go back to the “Field of Sorrow”, to wait for other early beings to succumb to lures of sexual attraction, before being reincarnated once again.