Stuff happens, as people say. No one could have guessed that at first from Ni Nyoman Kerti. Like most other children of the village, she followed her mother’s steps and knew when and where to make offerings. As for the why, the reason was usually given even before she could raise the question: there were duwe, or ‘owners’, to be paid attention to. Otherwise they would cause trouble.

Whether it was to find solace, or for some other reason, after school Ni Nyoman Kerti would regularly visit a small pelinggih shrine found just above the corner of the river on the dirt road to Abian Gombal. She enjoyed the view she had over the meander below. After making a short offering to the ‘owner’ of the place, she would sit on a big stone nearby and stay there for hours, looking over the water flowing and pondering over ‘dreams’ only she knew about. “I could not give a name to what I saw,” she now recalls. “Usually it was a woman, carrying a set of pejati offerings. But I was not sure. Now I know it was Ratu Nyang Sakti telling me I would have to serve her.”

These kind of ‘visits’ from the niskala, or unseen, world often happens to girls and since there was no dramatic seizure or anything, as happens with trances and possessions, no one paid attention. Yet, it was a sign that Ni Kerti was special. So she carried on with her studies until college, and also with her visits to the river shrine. She then became a market seller. No man had yet come into her life.

Then her father passed away. It happened all of a sudden. He disappeared in a morning to be discovered dead in a ravine two days later. He was quickly buried. The cremation, her mother said, would take place in three years. In the meantime, his body would be entrusted to Pertiwi, the goddess of the earth, and his soul put under the custody of the prajapati, in the temple of the death. She then threw up. And once, on the way back from Abian Tunggal, she almost fell into the same river ravine her father had fallen into. Something was amiss.

What does one do when something goes amiss in Bali? Does one address God to implore his blessing or protection? No. For traditional Balinese, God is too abstract a concept for this purpose. The cause of the mishap has to be something more direct, a more concrete force, like a ‘spirit’. One must to investigate the reasons why this spirit was acting upon us: what duty did we forget to do, and what should we do to restore the proper order?

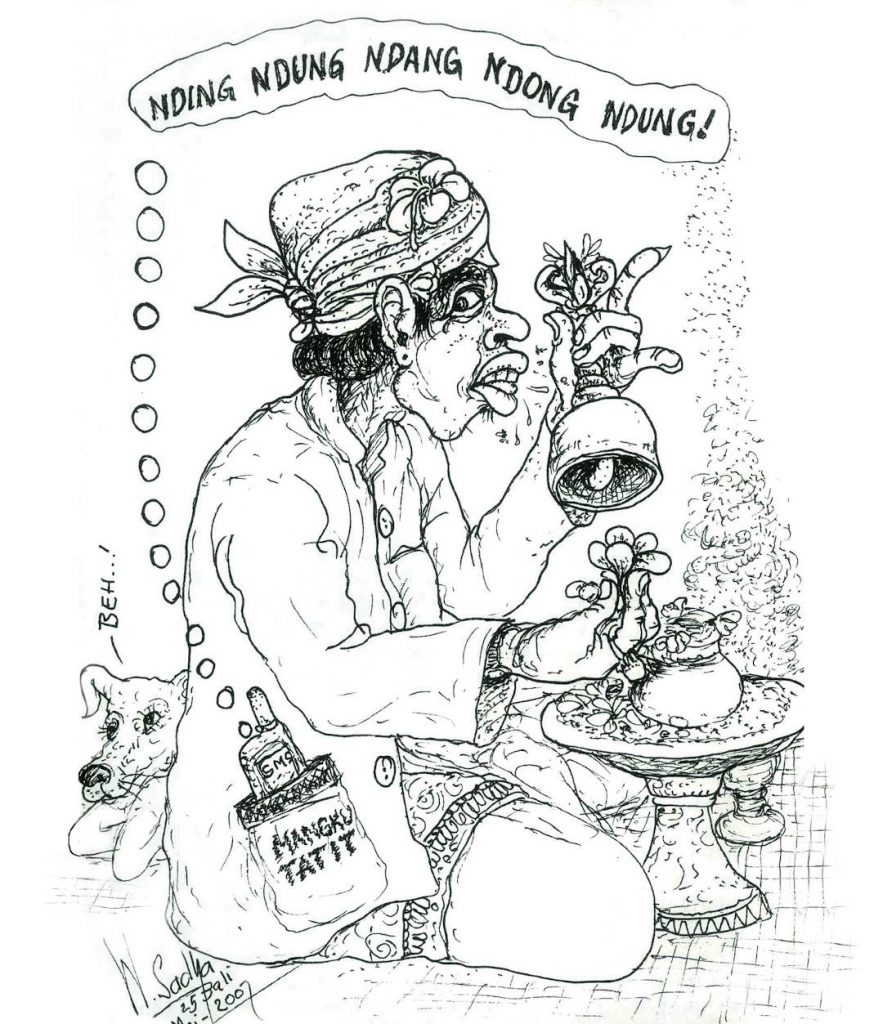

This is the job of a type of the balian tekakson, a type of ‘priest’ or even medium whose role is probably more important than that of the temple priests (pemangku) or the twice born sulinggih. When visiting a balian tekakson, the spirit is invited to speak through them, which is when they shall share what duty one has neglected, or whether one must serve a god.

Ni Luh Kerti found herself sitting next to the mumbling Jero Ketut, a famous Balian from Abian Timbul. The fumes from her pasepan swirling towards the heavens. The smoke went through the medium’s mouth, before the she addresses the gods with:

“O, you gods from Mount Agung, from Mount Batukaru, from Mount Lempuyang, from

the Peed Temple in Nusa Dua, I , a mere human ‘drop’, am begging you to

bring clarity to my problem; I am begging you to come down and talk.” (Batara

Gunung Agung, Batara Batukaru, Batara saking Lempuyang, Dalem Peed, Damuh

Batara nunas galang, mangda Ida Batara mepica baos.)

One notices here that no mention is given to any genuine Hindu god. Only the residing gods of the Balinese mountains are mentioned, together to the dwelling lord of Nusa Dua, lord of the Balinese negative forces. One also notices that instead of I, the priestess refers to herself as a ‘human drop’, in reference to the fact that humans are but water drops that come from the mountain.

Then came the reply, which was directed to Ni Nyoman Kerti through the Balian’s mouth. “So, my little drop, my child, even though I caused you to become ill, you would not recall me. You went to the doctor, it did not heal you, did it? So now, I am telling you, O little drop, to serve me (ngiring). Whether you like to or not! If you accept, you will be fine, and prosperous even. Help those who are ill, don’t be lazy, and address your prayers to me. So what do you choose, do you want to be ill or fine. (Damuh/pudah alit, manak Suba amonto baang sakit, sing masih inget. Mara jani, ke dokter, sing masih seget. Jani kene, damuh kapituduh ngiring!! Nyak apa sing. Yen nyak, seger teka, rejeki teka…Jani jalanang dharma pitulung, asal sabar inget ngrastiti manira. Maka nyak apa sing, encen kar piliha, sakit apa seger).

This was how Ni Nyoman Kerti became the guardian and temple priest of the Pura Taman Tukad temple. In later years she visited all the main island temples of Bali and brought their gods to Pura Taman Tukad with the status of visitor gods (pesimpangan). She thus kind of recreated in her little temple, now aggrandised in a genuine temple instead of a mere shrine, the whole traditional Balinese Pantheon.

So, what is the take away of this story?

None of these gods of the Pantheon has an original ‘Indian’ name. There is indeed little in Bali’s original popular religion that actually links it to Hinduism.

This does not mean that Hinduism has not taken place. It has had poles of diffusion for more than one thousand years. The Brahmins have long used Sanskrit-derived mantra. Hindu gods have long been part of literature. But Balinese tradition has resisted. Gods and ancestors reside on the mountain. Dead souls come down to reincarnate as dew or drops, and go back to the mountain heights after death.

Yet, this tradition does not resist anymore as it should. Like in Java where schooling wreaked havoc to Javanese Islam, schooling is wreaking the same havoc to Balinese tradition. Causalities of the type mentioned about Ni Nyoman Kerti above ‘do not make sense’ to the missionaries of neo-Hinduism ‘truth’. Indian rites such as Agni Hotra, totally unknown twenty years ago, are now increasingly more often practiced in the well-to-do educated circles of the island. Let us hope that the Balinese as a whole will be wise enough not to fall into the trap and protect their own tradition.