It would be interesting to make a survey, and hence know for sure, what you readers really know of Balinese cuisine. Excuse my arrogance, but I am pretty sure that many of you, when thinking of Balinese cuisine, have something in mind that did not exist forty years ago. Yes, much of what you find in restaurants nowadays has been imported, or created in this (short?) span of time. Exaggerating just a little, we can indeed affirm that, apart from the lawar (mixture of mashed vegetables, coconut and meat) suckling pig, betutu duckling, much of the dishes that you eat in restaurants, particularly in tourist resorts, has been created or imported in the last 40 years.

In fact, in those so-called happier days, food was mostly very ordinary: some rice, spices, a few vegetables, and occasionally half an egg. The food people normally dreamt about did not come from restaurants, but from the apparatus of power and belief or, rather, of power in belief, i.e religion. Let us give this affirmation a closer look through some typical situations.

If your family members were linked, by tradition, to a local palace as parekanattendants, what mattered to them was not so much the food they ate, but where it came from. The crème de la crème, I dare say, were the leftovers of their Cokorde prince. Not the pork ribs they somehow obtained from the princely kitchen, but if possible the food the prince had touched without actually eating it, his lungsuran, or leftovers. Actually it did not matter if you got just a little. You just took what you could and, once back home, you would mix it with your own rice and vegetables. Even if it was not very gusty and even stale, you ate it with all the more eagerness. Why? Because what you were sharing in was not only the Cokorde’s food, but his “spiritual power”. It was not without good reason, because where does the name of the word Cokorde come? From “cokor I dewa”, the gods’ foot, a reminder that a prince is “the foot of the gods”. In other words power was divine, and the food of the powerful became so too. I don’t know if you know of Hegel’s famous theory according to which the perfect slave is the one who does not know he is one. Here you are!

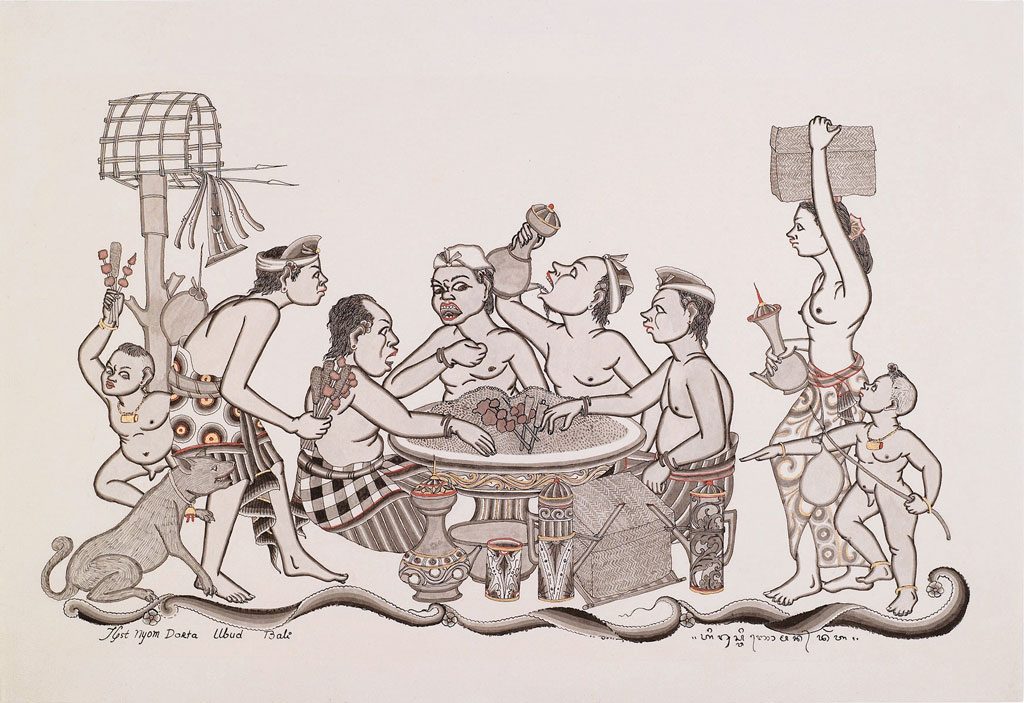

If a prince’s left-overs make for a most ‘delicious’ meal, you can imagine what it is with the gods’ left-overs. Because, democracy obliging, and religion remaining a main concern until today, one does not eat princes’ leftovers anymore, but one does eat the gods’ leftovers. Yes! You should keep in mind that the Balinese make “offerings” to gods and even earthly spirits. Those offerings consist, for the most part, of “food”. Of course, the small saiban offerings addressed to demonic forces are not the kind the Balinese would like to eat – they are put on the ground and the rice they contain is usually eaten by dogs. When it comes to banten offerings however, it is a different story entirely. These are offerings addressed to the gods, they are favourite delicacies; even if they don’t look or even taste so…

Addressed to heavenly beings, mainly ancestors, the banten are first taken to the temples and put on high platforms; it would indeed be an insult to the gods, and their worshippers, to put them on the ground. The outrage would have consequences from “out there”, the invisible niskala world. So, better beware. Always put the godly offerings where they should be, on a platform. This is why most temples have platforms visitors wonder about. Once on their platform, some offerings, for example the sarad “symbol of the world”, will stay there during the whole length of the gods’ visit (nyejer). Most, though, such as the gebogan, are brought there for a only short time; they are presented to the gods while the worshipper prays, and are then directly taken back home.

Let us sum things up. The offerings are food and are addressed to the gods. As short time visitors, these mainly ancestral god have to be presented with the best food, best dances etc, available to the village or the family. So they eat the offerings. Not physically, but symbolically. Automatically the offerings then become lungsuran ‘left-overs’ that will be actually consumed by the family or the temple worshippers. The latter thus partake of food that has been blessed by the presence of the gods. It is therefore sort of a sacred meal.

It does not stop here. Once the lungsuran offerings are taken back home, they may be consumed in private of course, as sacred food the family is shares within their compound. But the offerings may also be given to other people. It is actually an honour to give such food to visiting guests or to friends. Yet, it is not something neutral, a gift of ordinary food. For that reason, don’t try to give such lungsuran food to people who are socially “higher” than you, let us say a Brahmin or a Cokorda of the best lineage. It could be perceived as an insult. The Brahmin or prince may give you his godly lungsuran, but you may not give him yours.

In the days of old, some princes even used lungsuran to enhance their claim to power. How? Let us say you are a famous warrior prince from a lineage everybody considers as minor one – except you, of course. So what do you do? Do you go to war all the time? No. If you feel that one of your neighbourly princes is weak, you test him by sending him your temple lungsuran. If he accepts it, you have no need to go to war: he accepts your superiority. But if he sends you back the lungsuran you ceremoniously forwarded to him, it means he’s got guts and he’s ready to fight. Thus, in the days of old, the lungsuran was thus an instrument of power. Princes fought with one another not only with weapons, but also with symbols.

Trump should pay attention to that, when dealing with Kim Jong-Un.