People sometimes say that quarrelling is the salt and pepper of a couple’s life. Hardly a day goes by in Warni’s life when she does not quarrel with her Sasak man from Lombok (Sasak people are the main ethnic group from the island). They never set any special time for their daily fight: it might be early in the morning, at midday, or even in the dead of the night, when other people are sound asleep. To tell the truth, Warni’s man’s only job is to drive a run-down car that does not bring in much money. As for Warni, while her man is hunting for tourists she does nothing but wait for the money to come in.

And sometimes, indeed, the money just does not come. In such a time her man from Lombok stays the night away, rather than face the fight back home and suffer humiliation from the neighbour’s looks.

No fight goes on without their nosy words raking up the past. Warni demands her man to fulfil his promise of taking her to the penghulu (Moslem officiant) and marrying her. They have been together for more than three years now, she says, without the blessings of the Islamic law. But, Mamat, her man, has another view of the matter: he reminds her that he dragged her out of the gutter in the first place.

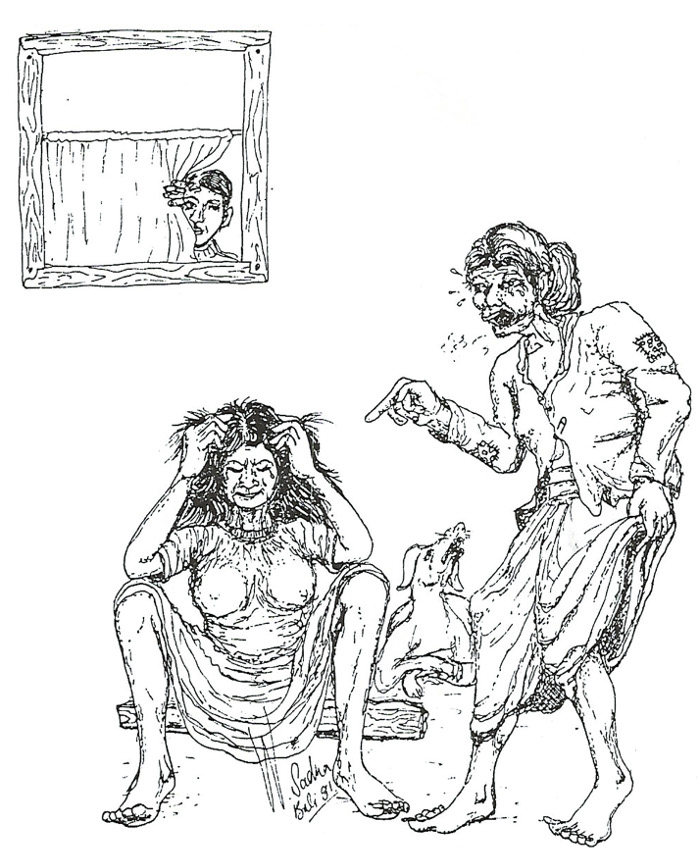

One day, an old lady came from the island of Madura: it was Warni’s mother. Before long, they were arguing loudly: “Why didn’t you follow my advice and “divorce” that man of yours? You have been leading a life of disorder for long enough. And haven’t even sent a single rupiah to your two children back home, hunger-stricken as they are. Have you forgotten them?”

Such were the mother’s words, pointing her finger at Warni, her face red with anger, and her trembling lips displaying a set of unsightly tobacco-stained teeth.

“It is all your fault, mother,” replied the daughter.” “You destroyed my life by your blindness. Why was it that you sent me to that Sudin to be his wife while I was still a kid? I was not ready and you knew it. I did not understand what he wanted of me with his hands and body. So why should you protest now and blame me like you do?”

Guilt-ridden, the mother sat down, her head hung in remorse. She had indeed found Warni a man when she was no more than thirteen, as was the Madurese fashion. But she felt that she had to. Warni was pretty and shapely, even at that young age. Her breasts were full and she would not bat an eyelid even under the most scrutinizing looks of men. Too many men were already coming and being welcomed with smiles by Warni. Therefore it had been thought wiser to find Warni a man.

Warni could not but follow her parent’s wishes. So, she married Sudin, and after two years, they had two children, a boy and a girl. But she was not ready for the responsibilities of motherhood and they fought everyday. One day, as could only be expected, Sudin disappeared, not to come back any more. He was in Surabaya, people said. And Warni was left home alone, with two young hungry mouths to feed.

Rather than yield to despair, Warni summoned up whatever willpower she had left. She had heard of Paradise Bali, the heaven of tourists, and there she went, looking for a job and roof over her head. First, she moved from place to place, wandering from friend to friend until, eventually, she settled down to a place of her own and a job: in the “alley of pleasure”, selling her body to whoever would have it. She soon had a large clientele: she was the prettiest of all the denizens of the house of ill fame.

But, after several years of being a “puppet of pleasure”, she felt the emptiness of it all. She wanted to find a man, a real man who would take care of her. Then, she met one whom she thought was capable. It was Mamat from Lombok. She moved in with Mamat. But, she was sadly mistaken. With Mamat too, she fought and quarrelled.

“I took you out of your hell of sin,” Mamat would say. “But you promised you would marry me,” she would reply. “So when do you take me to the priest?” This went on day after day.

One day, Mamat too disappeared. Only later did she hear that he had a wife and four children.

Now, day and night make no difference to Warni.

The weather is cool and damp in the alley. Nearby, one hears the croaking of frogs and the shrill chirping of crickets. A group of youths saunter along the alley, peering around. In the dim light of a red bulb of a warung, several girls sit waiting, their faces powder-white and eyes heavily made-up. There is a waft of cheap perfume in the air. Warni, one of the girls, looks blankly at the approaching youths. As ever, she expects pleasure and pain.

Jean Couteau (told by Wayan Sadha)