If we want to understand Balinese culture, we have to look deeply into its complex roots. Just as a tree draws its essence from an intricate and dispersed root system, the essence of today’s Balinese culture draws from ancient beliefs in animism and a pantheon of gods and ancestors, and the much later absorption of Hindu beliefs from Indian traders in the 5th century C.E.

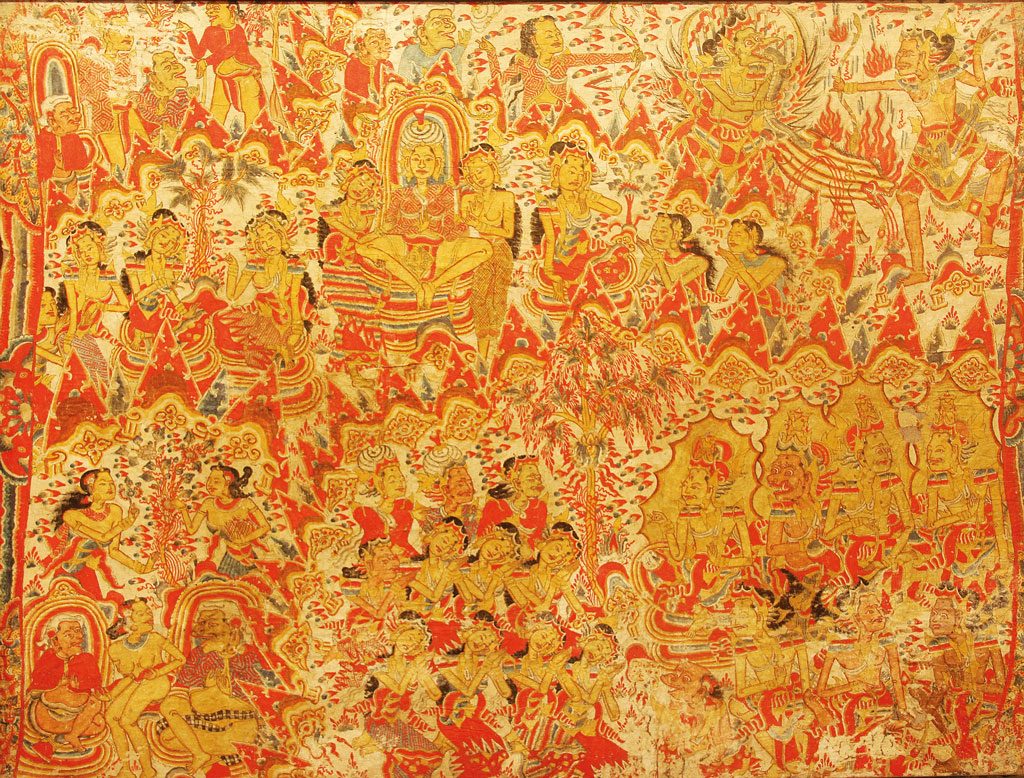

These two belief systems blend in the current culture, and they also blend and are demonstrated in the beloved puppet-show theatre, the wayang. Apart from its purely narrative visual character, to this author the most fascinating attribute of the wayang was the role it played historically in the transmission of Balinese values and knowledge before the arrival of TV.

Historically, Balinese people absorbed the details of their culture for the most part from the melodramatic dramas acted out on the screen of the wayang theatre. While very few people read, virtually all young village Balinese would typically watch puppet-show performances several times a month. Through the stories told and the jokes exchanged by the wayang puppets, they were taught what gods to worship for what purposes or occasions, what different ceremonies signified, and how to behave with family and fellow villagers. Wayang performances thus provided the framework of Balinese cultural knowledge.

An interesting aspect of the knowledge provided by the wayang is that it was not framed as a cohesive knowledge system structured around a dogmatic core. Rather ,the heart of their knowledge system consisted of symbols, and patterns of relationships among these symbols, encouraging the fluidity and lack of dogmatism of old Balinese traditions, something which is now changing with the rigidity of modern schooling and the intrusion of absolutes – “truths” – in the modern religious curriculum.

One of the best illustrations of the kind of wisdom channeled by wayang is found in the story of Arjuna* Wiwaha, or Arjuna’s wedding, as told in the poem written by Mpu Kanwa in the 11th century. In Arjuna Wiwaha the aim is to teach the audience how to achieve enlightenment while fulfilling one’s duties as a citizen.

The Wiwaha story begins with Arjuna meditating on the high slopes of the sacred Indrakila mountain. He is looking for enlightenment. The gods decide to test his steadfastness, so they dispatch seven amazingly beautiful heavenly nymphs. Are they symbolising sexual desire? Yes, and no. When Arjuna shows the strength of will to not succumb to the sexual goading of the seven seductresses, he is not simply resisting sexual temptation. He is dominating the sapta timira, the seven causes of darkness that inhabit the self and hence prevent enlightenment.

At that stage the god Indra intervenes, disguised as a Brahmin priest. He tells Arjuna that the genuine hero is not one who only strives for individual enlightenment and salvation, but who also strives for the well-being of the world.

After Indra is gone, Arjuna is suddenly attacked by Momo, a raksasa (monster) in the shape of a boar who symbolises spite and evil embedded in the ego. Upon seeing all the havoc created by Momo, Arjuna takes his bow and shoots at Momo with one of his magical arrows. The raksasa is hit and collapses, dead. Las, a handsome warrior appears from nowhere to claim that it was he, and not Arjuna, who killed the monster. It seems the two arrows have merged into one. They quarrel, then fight. Shockingly, Arjuna is defeated. However, it is immediately revealed that he was defeated by none other than Shiva. Arjuna then launches into an ode to the greatness of God, the origin and destination of all. This is evidence that Arjuna has achieved enlightenment; he has repulsed temptations by the seven causes of darkness (the 7 nymphs/sapta timira), killed evil within the self (Momo/boar), and overcome ego to surrender to the greatness of God.

Yet, genuine enlightenment does not belong to this world and therefore before he can enjoy his new-found enlightenment, Arjuna must first fulfil Indra’s dictum that he must strive for well-being for all humanity. He must go down the mountain and be among ordinary humans where he must help the gods fight the evil raksasa, Niwatakwaca, who is threatening the balance of the world with his deceitful, evil talk. Luckily, unlike Arjuna, the raksasa never resists temptation. Arjuna knows this and devises a trick. He sends the most beautiful nymph in the world, Supraba, to tempt his enemy. Niwatakwaca falls into the trap and in an intimate moment, confides his weak spot, the soft palate in the roof of his mouth, to Supraba. She, then, tells Arjuna who sends a magic arrow to pierce the raksasa’s vulnerable soft palate and shuts his evil mouth for good.

Should we conclude that because Niwatakwaca spoke evil, and that, in ending the raksasa’s ability to speak at all, Arjuna had fulfilled Indra’s demand that he strive for the well-being of the whole world, not just for his own spiritual enlightenment?

Might we not, therefore, speculate that the world would be better if it had a few Arjunas who, having achieved perfect self-control, might then be able dispatch a few well-aimed arrows deep into the metaphorical soft palates of the local and global raksasas who speak maliciously and deceitfully of others and wreak havoc all over the place?

Clearly, the world needs an Arjuna today. I am wondering if the leaders of the United States today represent Niwatakwaca or Momo – or both. And I desperately hope, for the sake of the whole world, that the country finds an Arjuna sooner rather than later.

*Arjuna, as you may know, is one of the Pandawa, the five brothers at the core of the ancient Indian Mahabharata epic. Yet, apart for the name of the hero, the story told by the dalang (the wayang puppeteer) has little or nothing to do with its mythological Indian reference; the dalang simply uses the name of the Mahabharata’s highly respected hero, Arjuna, to weave a typically Balinese narrative.