Traditionally the key element of the Balinese religion is not the Hindu gods, but the ancestors. It is to these ancestors that people address their daily prayers.

Whenever sons create a new family in a new location, they set up a new family temple or sanggah. From here, they add successively from generation-to-generation: the sanggah gede for local kin, then the pura dadia at the supra-village level, up to the kawitan for founding father’s temple in Gelgel or in another historical centre of Bali.

In other words, the genealogy is duplicated by a system of clan temples.

All Balinese are expected to participate at the temple anniversaries of their clan temples, when their ancestors come down for visits to be welcomed by dances and fed with offerings etc.

These festivals reinforce the clan’s identity. They are also networking forums and an arena of status contention. It is better to be member of some clans than others: some clans are prestigious owing to their high caste status – Brahmana, Satria, Wesia.

On the other side some Sudra clans are reputed ‘rich’ or ‘powerful’. Congregations thus become arenas of status contention.

In the process of time, some people lose touch with their clan of origin. They are members of a local sanggah gede temple, but don’t know to which kawitan of origin they are ultimately affiliated. So they only worship their ancestors locally. They don’t know to which larger clan they belong (for example Arya Belog, Pasek Gelgel or Pasek Kayu Selem).

Other people have lost their caste rank. Take the example of a lower aristocrat who had to flee to escape the wrath of his lord. He was accepted ‘as refugee’ in a remote village on the condition that he gives up his superior caste status (nyineb wangsa) and thus becomes a commoner.

Then his descendants forget their aristocratic origin and blend into the local population. The fact that Bali was politically divided prior to colonisation reinforced this fragmentation.

Some people do not care not to know their kawitan. They move to the city and make do with their ignorance by becoming ‘modern’ neo-Hindu — i.e. by adopting Indian Hinduism.

But for the majority of them it is the opposite that occurs: any illness, accident or an economic failure will be seen as a ‘signal’ that there is something awry in their relation to the invisible world (niskala): their ancestors feel neglected.

When this happens, the typical Balinese will do what he or she has to do: try to locate the lost temple of origin (kawitan) and gain acceptance as a member of its congregation. Then restore the link to the lost ancestors to get their protection instead of their wrath.

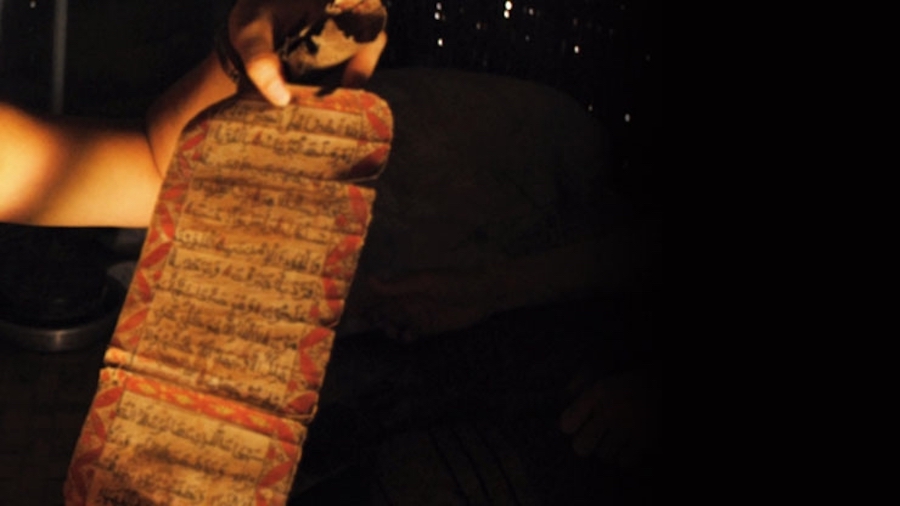

There are several ways to proceed, usually under the guidance of the sub-clan leader. The easiest way is to consult lontars (manuscripts) that may be kept by families or to listen to stories told by elders about their origin.

Once this is done, the best way is to consult a specialist of chronicles (babad). This specialist may find traces of a character who was involved, let’s say, in a political tussle, generations ago, and had to find refuge on the other side of the island.

This character might be the ‘lost’ link . One might also check with a babad specialist from the Puri Klungkung – Klungkung being the more revered centre of power in Bali.

Besides investigating the chronicles, a complementary way is ‘to make the ancestors talk’ (nunas baos). In practical terms, it means visiting a balian (medium) whose job, against a small offering, is ‘to call down’ the right ancestor from his invisible abode so that the latter may tell the ones he calls his ‘children’(cening) what to do.

“I was hidden, my children, now know my name”.

Once his name is known, it is easy to identify the kawitan temple of origin. The designated ancestor has often demands to convey. Usually a guru piduka rite, to wipe out all the negative influences brought about to the local clan on account of the neglect of its duties toward its ancestors.

But often things are not as simple as that. Some members of the family may not believe that the medium was the right one or pinpointed the right ancestor, hence the right clan and congregation.

For this reason people often consult several mediums and the decision is taken after much discussion and bargaining among the clan members. Some people may dream to connect to a clan of higher status, or to recover what they deem to be their forgotten aristocratic status.

Other people are wary of such claim. For low caste people, there is a tendency to try to connect or reconnect to an Arya group –the Arya, themselves subdivided into many clans, being the clans that comprise all the descendants of the Javanese invaders from the 14th century (1343).

Yet, even if a babad specialist and several mediums decide that you should become a member of the, let’s say, Arya Benculuk clan, this does not mean that the request will be accepted. The targeted clan has to consent first; it usually consults its members and submits its own conditions: usually a penanjung batu contribution. But nothing is sure. There might also be propitious or unpropitious ‘signs’, that may lead to the refusal or acceptance of the request.

Under normal circumstances, if the process is open, the medium well-known, and the candidates are looking prosperous, there are good chances that the new sub-clan will be accepted. It must simply get ready to soon receive requests to “modernise” the temple, hold a big temple festival etc.

As one sees above, the clan system may rest on genealogy, but, it often happens that this genealogy is mythical, if not manipulated. There are indeed ways for a Sudra, to discover himself to be an Arya and the following generation, for his sons to gain full acceptance as Agung, thus as aristocrats. Status may change without anyone being aware that such results have been manipulated.