The Balinese-Hindu have a day dedicated to the goddess of knowledge, Saraswati. She is said to rule over books, lontar manuscripts and all objects of knowledge. On her festival day, all these objects may not be used, as they are presented with offerings. The ritual is done in one’s private house for one’s own books, but one also visits, with offerings, all the balian usada (traditional ‘doctors’), or other people of knowledge one may have consulted since the previous Hari Saraswati (Saraswati Day).

Among the offerings one usually finds a uniquely shaped rice effigy in the shape of two geckos (male and female). The gecko, known locally as the ‘cicak’ is the traditional symbol of Saraswati: the gecko is said to have a spiritual sensitivity with the dimensions of Purusa and Pradana. But also, the cicak listens to people’s secrets, even in their private chambers. It is thus all knowing (best compared to ‘a fly on the wall’).

Why does the day of knowledge fall on this particular day? This is when it becomes interesting. Saraswati, or the day of knowledge, is the last day of the 210 day pawukon (also pewukon) calendar, which comprises 30 weeks (wuku) of 7 days, and defines the days of market and most temples anniversaries. Hari Saraswati and the names of all the individual wuku weeks are related to the Balinese story of the prohibition of incest, the story of Watugunung, Bali’s Oedipus.

The Myth of Watugunung – The Symbolism of Hari Saraswati

In this long-known myth, Watugunung, an ancient king, commits a mortal sin: he unknowingly makes love to his own mother. This unnatural action is discovered by the gods who, curiously enough, instead of killing him, make Watugunung the protector of the calendar, and the master of its final (30th) week. His mother is made the protector of the first week, thus the beginning of the next cycle. Week 1 of the Pawukon calendar, and yes they are all named, is known as Sinta, after the mother; and Week 30 is named Watugunung. For clarity’s sake, this is the same relationship between December of one year and January of the next.

This is effective symbolism, as what therefore separates the ‘cycles’, i.e. the incestuous son and mother? That separation is Knowledge / Awareness, i.e. Saraswati Day, the last day of the calendar.

Saraswati embodies the awareness of time through the organisation of the calendar; it also embodies the awareness of the need to prohibit incestuous relations — this is at the root of civilisation! The concept of time and the need to regulate social life through religion and calendar are thus born at once from the same Balinese myth.

Returning to the comparison to Watugung’s Greek equivalent, who was also subject to a similar unnatural relationship, Oedipus instead blinds himself and goes about the world cursing the gods.

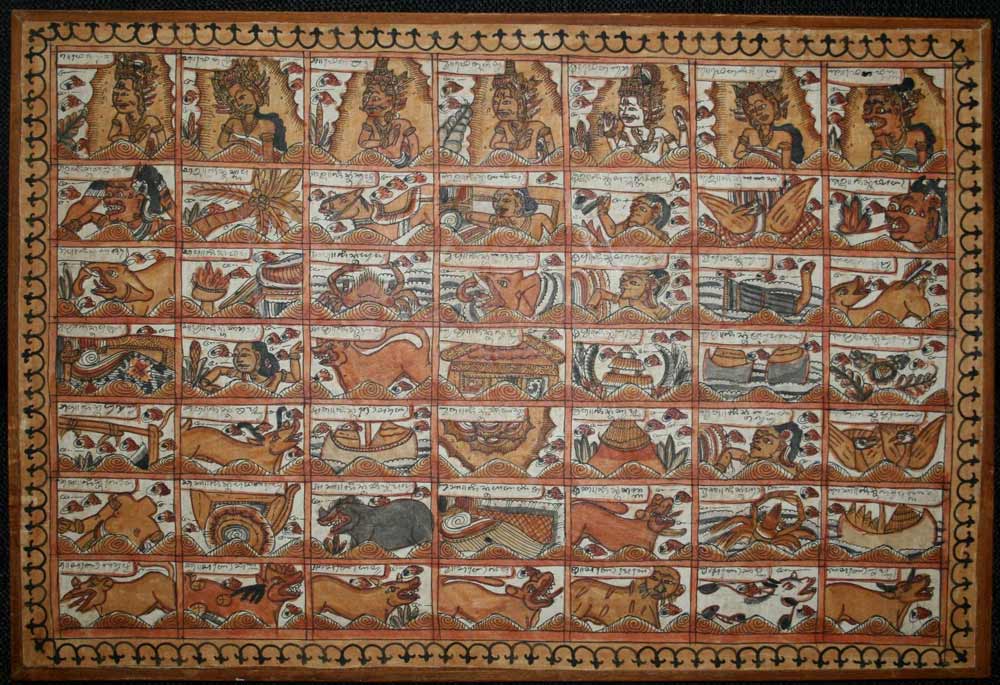

The Complexities of the Pawukon Calendar

The wuku week of seven days is not the only inner cycle of the Pawukon . The Pawukon system actually consists of a computation of ten types of different cycles, called wara, from the “one-day cycle” (ekawara ) to the “ten-day cycle” (dasawara ). Each “day” of each wara cycle has its name and value, defined by its positioning on the cosmic rose of the wind or pangider-ider. In practice, the wara cycles which are the most important for ritual purposes are the three-day cycle (triwara), the five-day cycle (pancawara ) and the seven-day cycle (saptawara ).

The way the days of these various waras add up define the pure, or impure, quality of the “day” in question. In this complex computation, the crossings with the day Kliwon of the five-day cycle, are the most important. To the crossing of Kliwon with three days –Tueday, Wednesday and Saturday– of the heptomad, correspond the main holidays of the calendar: Buda-Kliwon (Wednesday-Kliwon); Anggarakasih (Tuesday-Kliwon) and Tumpek (Saturday-Kliwon). All these three holidays recur every 35 days, and, thus, six times a Pewukon “year” of 210 days, corresponding to their crossing with the six-day week. Also very important in the ritual is the crossing of the Kliwon day of the five-day week with the Kajeng day of the three-day week, occurring every fifteen days. Kajeng-Kliwon is day when one makes offering to the demonic forces.

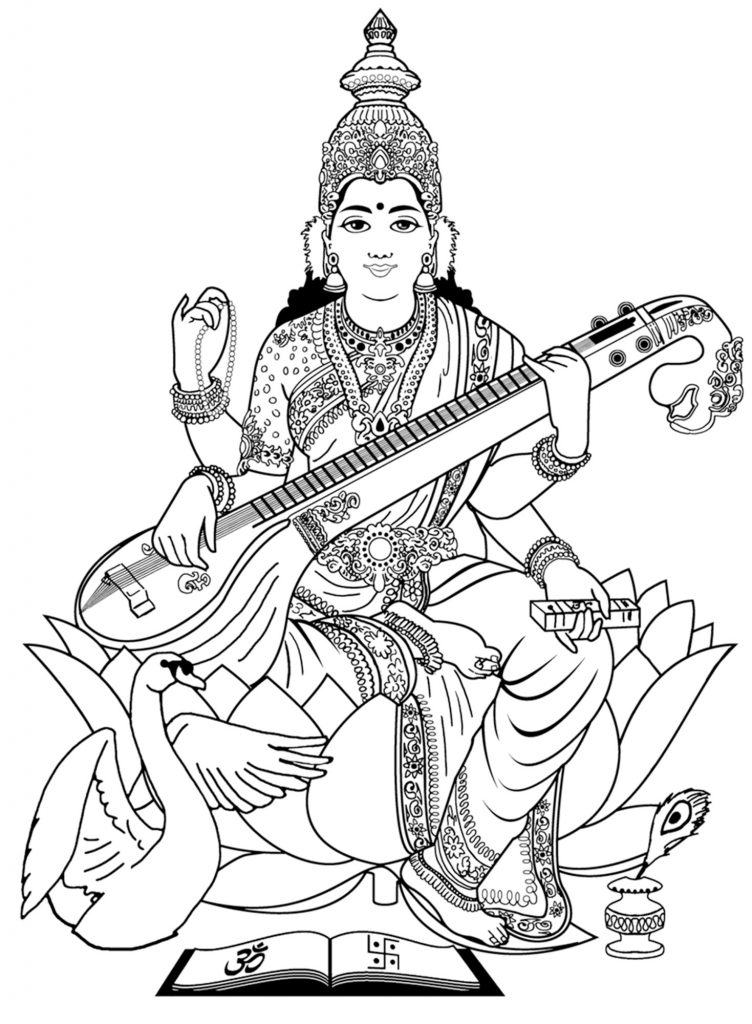

Depiction of Saraswati, Goddess of Knowledge

Whilst old traditions saw the cicak as a symbol of the goddess, as the Balinese started defining itself as Hindu in the middle of the last century (at the same time as modern education was embraced) they adopted the Hindu Indian Symbolisation of Saraswati, which one now finds in numerous Balinese representation of the goddess.

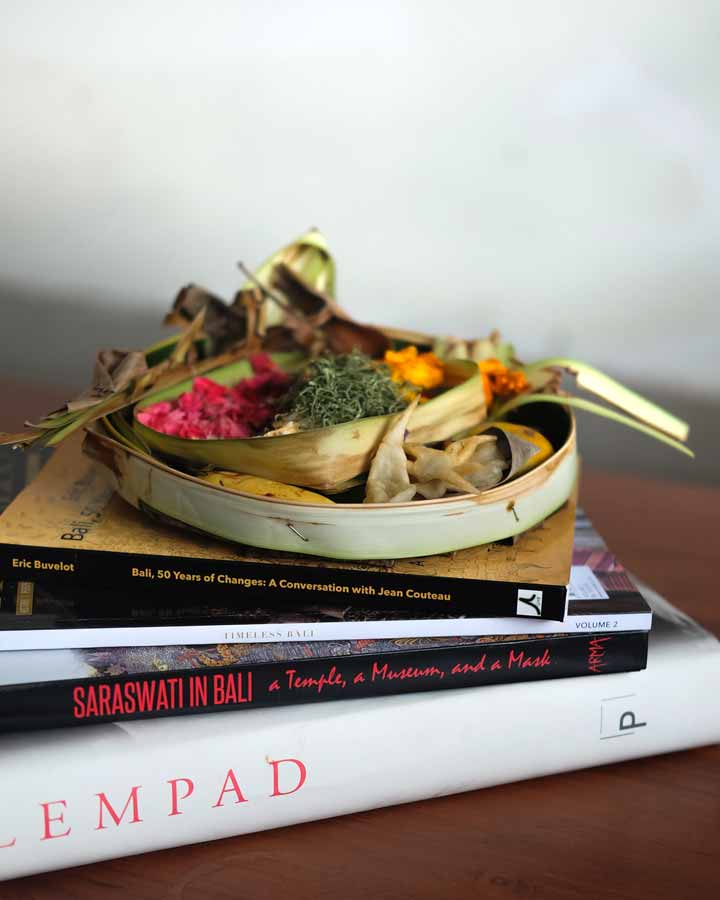

Saraswati is thus symbolised by a beautiful woman with four hands, riding on a white swan among water lilies. Her hands hold a lontar, the palm leaf manuscript; a chain, the symbol of knowledge as something that never ends; and a musical instrument, the symbol of science as something that develops through the growth of culture. During Saraswati Day, schools and institutes of education across the island will be flooded with students all dressed up in their ceremonial finery for a session of communal prayer. Resource books are piled high and blessed with offering of fruits, flowers and a sprinkling of holy water. Students take this opportunity to pray for guidance with future studies and to lead a harmonious life that adheres to the basic guidelines of Hinduism.

Saraswati is soon followed by Hari Pagerwesi, or the day of the iron fence.