Before bottles of Grey Goose or Dom Pérignon ever reached the island, the libation of choice was always arak. This island moonshine was not just a delicacy, it was a craft. Today, these arak artisans continue to produce using age-old methods, supplying the local arak scene from their humble, home-based distilleries.

‘Arak – Made in Bali’ Mini-Documentary

You would never find it if you weren’t looking for it. Tucked away in a pocket of one of Sidemen’s many valleys, the sleepy village of Tri Eka Buana goes about its quiet existence with near anonymity. The single road that leads into this rural hamlet is typical of any Balinese village, or desa. Farms interspersed between homes, chickens and dogs run alongside the odd motorbike that sputters by. Yes, just like any other village. Until you hear the shouts.

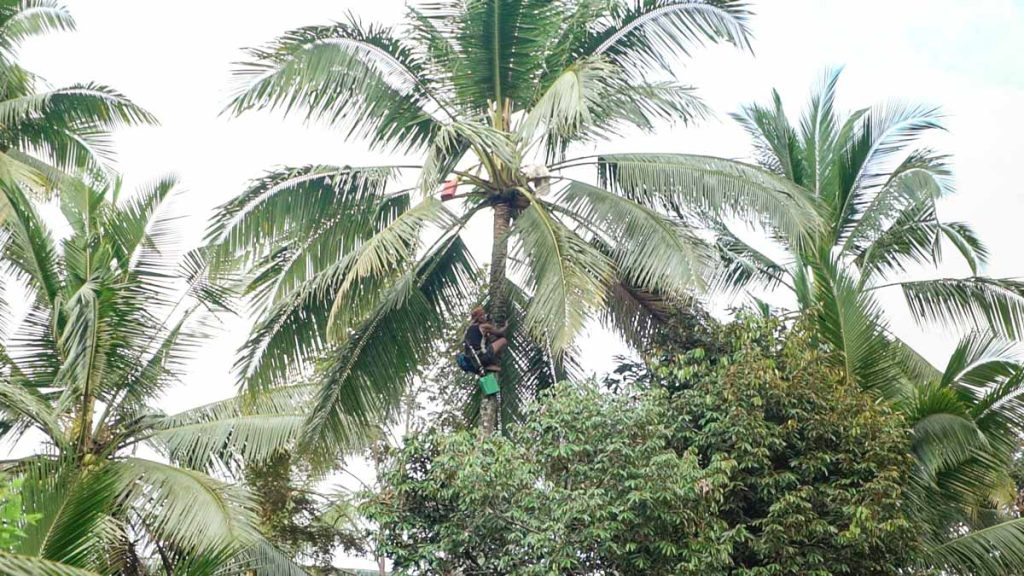

Anywhere between 6am to 8am, or 4pm to 6pm, distant shouts echo through the valley floor, reverberating across the still paddy fields and above the trickling streams that run through the village centre. The shouts sound like they’re near, but a quick scan reveals no one. “Up there!”, my brother points out. Squinting towards the sky, we see a palm tree shaking and notice a man seated on a tender branch bending with his weight. His shouts are directed at his neighbour, who sits almost parallel to him, 15 metres above the ground on a distant tree. Suddenly we notice more and more men quite literally hanging out in the coconut canopy.

Astounded, we walk towards the family compound of our contact, I Wayan Lemes Indrawan, one of the local arak farmers. As we enter, we watch as one of the canopy crawlers makes his way down the narrow, snaking tree trunk. He has no rope or harness on, nor shoes nor gloves nor helmet. The hardened soles of his feet planted against the bark and his hands clasped together, hugging the trunk, he slides down effortlessly. Wrapped to his waist is his bounty, a bucket filled with a cloudy white sap. This is Wayan’s older brother, Nyoman Wangsa.

“I work with my brothers and their families”, explains Wayan Lemes. “My whole family are – and were – arak farmers.” This is true for the majority of Tri Eka Buana Village, as close to 90% of the families make their money through this distilled palm wine.

“To be an arak farmer, you need to have land with coconut trees and you need the tools: a sharp knife, buckets, and a furnace,” he says, pointing to a blackened cauldron. “You must also consider the risk. Are you physically strong and healthy? Farmers must climb around 15 trees in the morning, and another 15 in the afternoon.”

Whilst many know of arak, not many understand where it comes from or how it’s made. In Bali, it is made from what has always been abundant: coconuts and rice. At Tri Eka Buana, and for the Karangasem Regency, palm-based arak is what is produced.

Growing at the top of the coconut trees are coconut flowers bunched into an inflorescence. Each tree can have one to three inflorescences, and it is from here the cloudy white sap, known as tuak, is collected.

Containers have been fastened to the inflorescences, cut to a stump for the sap to ooze out freely. Everyday, a farmer climbs to the top of the palm trees to collect, filling a bucket they bring with them with the tuak found in the containers. They freshly cut the inflorescence again, refasten the container and head back down. They will collect around three litres of tuak per tree on a good day.

The tuak is stored in a big bucket together with coconut husks for around four days, or until they have managed to collect up to 80-90 litres. The liquid, also referred to as palm wine, ferments almost instantly, in two-hours it can reach 1-2% alcohol content. Before that, it is sickly sweet, tasting of old coconut water and baking soda.

Wayan shares an arak production area with his brother Nyoman. Nyoman’s wife, Ketut Parni, manages a lot of the distilling process. Their production area consists of a furnace fashioned out of an old and hardened coconut tree stump. Hollowed out, the four-day old tuak is poured in, sealed, and made airtight using the paste of ground-down talas leaf which acts a glue.

The furnace is heated from below using wood and bamboo, similar to the methods found in a traditional paon, or Balinese kitchen. Then, it’s the waiting game. After about four hours, the distilled vapours rise to the top of the stump-furnace into a metal tube, which then runs through a tank of water, cooling the vapours into a liquid. Finally, a clear liquid trickles out and the arak is collected in a container.

“It’s all about volume control”, explains Wayan. “How much we make depends on what percentage of alcohol we’re aiming for.” To make an arak of 30% alcohol content or more, they only collect the first 10 litres. Anymore and the solution gets diluted. “Normally, the local drinkers want arak between 15-20% alcohol, so we collect around 20 litres.”

Another Wayan (Wayan’s older brother) pours the freshly collected arak into a glass and shares it with us. Like many hard liquors its fumes strike the sinuses hard and sharp, but the arak has a sourness to it. Apparently this sourness is a way to identify the ‘real stuff’. A sip of the palm moonshine is a serious jolt to the senses too, especially at higher alcohol quantities when it is referred to as arak api, or fire arak, since it catches alight when exposed to a flame.

Wayan sells his arak to warungs (local eateries) in the area and also in Denpasar, usually for around Rp.35.000 for 600ml depending on the alcohol by volume (ABV). This amounts to roughly around Rp.580.000 for 10 litres at 30% ABV, or Rp.833.000 for 20 litres at 15% ABV.

“What worries us farmers the most is the producers that make counterfeit arak. We literally risk and gamble our lives to harvest the raw materials, the tuak,” shares Wayan, with visible frustration. Previous cases of methanol poisoning with fake arak that plagued Bali’s party-scene was particularly bad for the legitimate arak producers. “We’re also vulnerable to changing prices; the cost of our lives shouldn’t be subject to economics like this.”

The risks Wayan speaks of are true. A week or so before visiting him, one of the farmers from the area fell from the top of a coconut tree, lasting three days in hospital before passing away — others have broken limbs, or been paralysed.

Bali’s Provincial Government has officially recognised traditional arak making under law [Governor’s Letter No 1. Year 2020], stating it is part of Bali’s cultural heritage and thus should be protected and developed. Wayan continues to hope for more support from the government in improving production, hygiene, licensing and selling.

Local arak became increasingly popular in the year 2020, perhaps driven by the demand for affordable alcohol. Arak is bought, infused with fruits and flavours, then branded and rebottled, making it popular among younger generations. It is touted to have health benefits too; when infused with herbs, roots and spices, it is considered a health tonic categorised as arak jung.

Arak also plays its part in religious worship. During Balinese Hindu prayers, arak is poured onto the ground, metabuh. This is as an offering to the bhuta kala, the demonic forces who must be placated as much as deities must be praised. Thus, there is always a demand for arak as the tetabuhan.

“What I have taken from nature, I shall return to nature. [During prayers] I give the arak as a thanks, as from nothing we have been given something. From arak we are able to have a home, food, a family, look after our children and can continue to conduct our ceremonies.”

It is clear that this humble palm wine is central to the livelihoods of Wayan, his family and for the families of Tri Eka Buana. Asked whether he believes traditional arak will continue with the next generation, he says that all depends on how it is valued by society and the government. The prize must value the risk, and the risk they take is that of their own life.