Balinese food is often over-simplified. In fact, most foods are. Reduced to the singular dish that is brought to our table. As we smell, bite and chew, our taste buds absorb the flavours and yes, “Delicious!” registers our brain, “Have another bite.” What each scrumptious bite doesn’t tell us, however, is that every herb and spice tells a story; every dish, a memory; every kitchen, a ritual.

This is certainly the case in Bali, where food and cooking are intertwined with philosophy, community and culture. So, in fact every bite does indeed contain within it a little lesson, a little discovery of the island of the gods.

Paon philosophy

“The kitchen is a holy place”, explains Jero Gede Yudiawan. He points at three different stoves positioned at the centre of his traditional kitchen setup: “This represents the cycle of time: birth, life and death; past, present and future.”

Such symbolism is abundant in the traditional Balinese kitchen, known as a paon. The stove is the realm of Brahma, symbolised by fire; a large water jar is Wisnu; Dewi Sri the goddess of rice is found in the jineng barn, where the rice is kept. As for Siwa, as ‘air’ he is all around. The pestle and mortar symbolic of the yoni and lingga, the merging of the microcosm and macrocosm, and as they are ground together they represent the turning of the world, the eternal process of creation. Quite the feat for a little spice grinder.

Jero Mangku Yudi, as he is now called since accepting his responsibility as a temple priest (mangku), opened his restaurant Dapoer Bali Mula on the foothills that surround Les Village, Buleleng, northeast Bali. It has become a sort of museum for the island’s culinary heritage. Lined along the walls are antique guci, Chinese ceramic jars used to hold his own arak (a local spirit). This he makes in his workshop using an old method, distilling tuak (coconut flower sap) and allowing the arak to trickle down a 12-metre bamboo pole. Here he also cooks his own gula aren (jurah in Balinese), a thick and delicious palm sugar; and also an intensely fragrant coconut oil made the way his ancestors used to.

The traditions of the old Balinese kitchen are on show at this one-of-a-kind restaurant, ‘Bali Mula’ being the term for the island’s original inhabitants. But it isn’t simply the setting: the food cooked and served here aims at representing Bali’s broader culinary offerings. “I want people to know that there’s more to Balinese food than just babi guling [suckling pig]. Here I cook squid, tuna, duck, chicken, all the Balinese way, with some of my own twists. I will always use the produce from Desa Les first, and other parts of Bali.” His dishes and all the produce he makes or uses are a showcase of the island’s incredible bounty, and the traditions used to make them.

“All I am doing is restoring, preserving and protecting what has been given to us by our ancestors; whilst uplifting the potential of our village,” says Jero Yudi.

Passing the torch

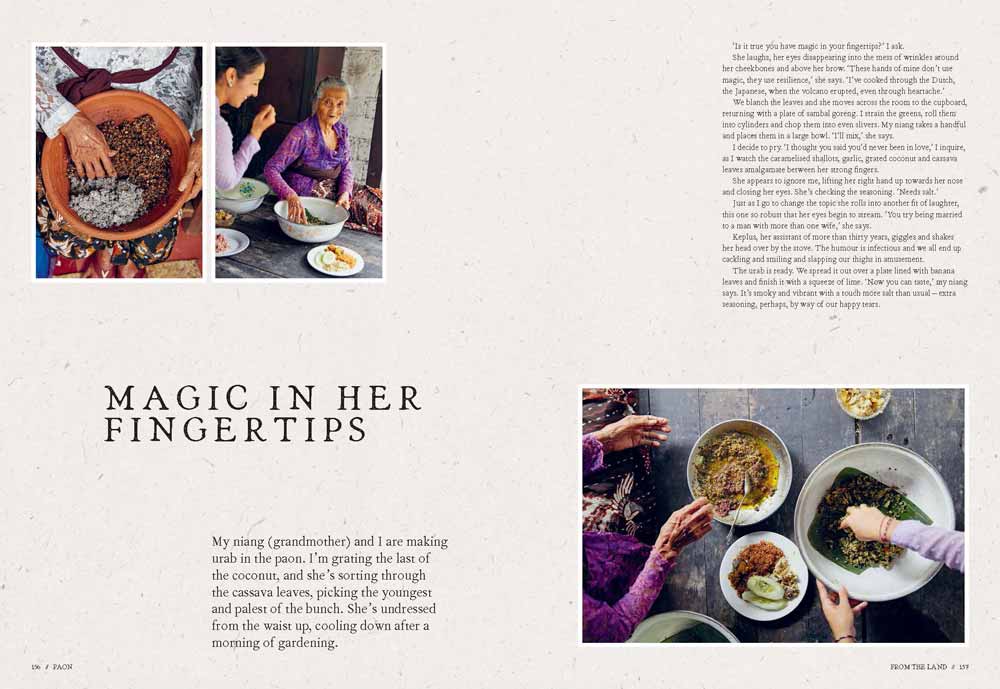

Jero Yudi is implying that food is very much an inheritance from one’s elders, something that Tjok Maya Kerthayasa is also very aware of. “Learning to cook with my grandmother was important to me on a personal level, after having lived abroad for many years,” she shares with NOW! Bali.

In 2022, Tjok Maya published a book with co-author Chef Wayan Kresna. ‘Paon: Real Balinese Cooking’ takes its readers into the depths of culture and cuisine on the island of the gods, simultaneously exploring recipes and ritual, technique and tradition, ingredients and intuitive cooking. After a successful career in Sydney writing for Australian Gourmet Traveller, Tjok Maya returned to her hometown, Ubud, with a mission to document her grandmother’s recipes and become a bridge of understanding Balinese cuisine, both for outsiders and future Balinese generations.

“There’s an aspect of learning the ways of a precious generation. Women and men who cook in a vastly more connected way than we do today. If I had not explored my niang’s cooking, I may have missed out on an opportunity to understand just how integrated her cooking is with the Earth, the elements, and with Spirit. How food can be healing for both the people that consume it and the environment it comes from. How we can utilise so much of what already exists around us, and the incredible flavours and health benefits that stem from this practice.”

Some of Bali’s dishes are said to have a history that spans back to the Majapahit, the Javanese-Hindu Empire that invaded Bali in 1343. The cooking method of the classic betutu dish (cooked underground with hot stones and coals), as well as the ritual lawar minced vegetables are believed to be an inheritance from this ancient era.

As Tjok Maya mentions, the environment is certainly an important factor in cooking. Geography, landscape, climate, all come into play to create slight regional distinctions, even of the same dish — inadvertently causing some friendly competition between the regions.For example, the staple lawar, cooked for every ceremony, is rumoured to have more grated coconut if near the coast, and more jackfruit if made in the mountains. “We have to make do with what is given to us, what is around us,” an arak farmer once shared with me.

Sugar, spice and… everything!

The abundance of naturally growing spices and herbs has clearly influenced the richness of Balinese cuisine — and indeed Indonesian food in general. On the east coast they are blessed with abundant seasoning: natural sea salt is dried and made on the beachfronts; and tabia bun, a local long pepper, sharp and nippy in flavour, is found growing in the hillsides.

That is only the beginning, of course. Many Balinese food is rooted in a staple spice mix known as base genep or base gede, a rich, sharp and complex paste that consists of at least 15 spices. Shallots, garlic, turmeric, galangal, ginger, lemongrass, candlenut, chilli, bay leaves, and more, pressed and processed into a powerful formula of flavour, quite literally the ‘base’ for many savoury Balinese dishes.

Such a bold and memorable flavour profile makes such dishes the face of Balinese cuisine – the ‘must-try’ foods. But it isn’t fully representative. “I found myself pleasantly moved by the very simple dishes that I encountered and just how wholesome they are,” reflects Tjok Maya. “Daluman leaves squeezed into a nutritious jelly, cassava roasted over wood-fire with a dash of coconut sugar and sea-salt… I wish people knew just how plant-driven the traditional cuisine is – how many different leaves, shoots, flowers and rhizomes can be cooked and eaten here in Bali.”

Balinese cooking is in fact a lesson in resourcefulness, as many ingredients transcend what is considered the ‘normal’ edible part of the plant. Just about every part of the banana tree is used in cooking: the fruit is made into market snacks (pisang rai), leaves are used to wrap and flavour (tum), its trunk and flower chopped and turned into stew (jukut ares). “I feel that there are so many more layers to the cuisine that can be explored once you dive into the plant world. Plants grant us access to the medicinal side of the cuisine, as well as the diversity of the island’s natural landscape,” continues Tjok Maya.

Festive feasting

Though Bali’s cuisine certainly encompasses many interesting plant recipes, meat will always have its place. Not due to dietary preference, but because certain dishes are wajib, customary, when it comes to Bali’s religious ceremonies. As food is not only blessed by the gods, it is also cooked for and served to the gods too — explained in detail by Jean Couteau in his article ‘Food for the Gods’.

During the most important auspicious days, especially Galungan and Kuningan, delicacies like babi guling (suckling pig), ayam or bebek betutu (chicken or duck betutu), urutan (Balinese pork sausage), sate lilit (minced fish satay) and lawar are brought to the temple, symbolically served as an offering to the gods and ancestors before they are allowed to be consumed, by humans that is. These were once considered special, sacred foods, now open for the public to taste and savour.

Festival feasts hold another important function when it comes to Balinese food. Its preparation and enjoyment are important communal activities, bringing families, banjars (neighbourhood organisation), or even whole villages together, depending on the scale of ceremony.

Such a display is seen on the morning of the famed pandan wars, or mekare-kare, in the traditional village of Tenganan Pegringsingan. Early in the morning, the residents gather to prepare their ceremonial feast, everyone lending a hand, taking a role. Prior to the uproarious events that will come later in the afternoon, it is a calm and serene scene of communal cooking.

In Tenganan it is the men who cook, as the women are busy laying offerings around the village on this auspicious day. Huge bowls of spices are being mixed (the ‘base gede’ that will flavour much of the food), the urutan pork sausages freshly stuffed, pork belly deep fried, a giant pot of jukut ares boiling in the corner. Outside, in the village centre, the younger men are grilling sate babi (pork skewers) and sate lilit ayam (minced chicken skewers). One of the ingredients was the losing chicken of an early-morning cock fight, also done for ceremonial reasons.

The feast will be enjoyed after the pandan wars are complete: the ‘contestants’ have their pandan thorn-wounds treated with a natural paste (turmeric, galangal, and vinegar), and then sit down together to eat in a communal style known as megibung, all the dishes cooked earlier laid out on a banana leaf for all to share.

For the Balinese, it is clear that food is about ritual, community, offering, family, inheritance and environment. For the rest of us on the ‘outside’, what we savour may just be food, devoid of sentiment or memory. We can however appreciate just how much Bali’s cultural heritage is present in cuisine. That each bite tells its own story: perhaps of philosophy, of produce, of geography, or perhaps even of someone’s niang, whose very recipe we are lucky enough to enjoy.

Find out more:-

Dapur Bali Mula

Les Village, Buleleng Regency

+6281337130088

@dapurbalimula

Paon: Real Balinese Cooking

Published by Hardie Grant (hardiegrant.com), also available in good bookstores in Indonesia

Maya Kerthyasa on Instagram: @mayakerthyasa