Cloths have a special place in the cultural heritage of Bali, the use of textiles a living tradition in itself. Imbued with symbolism and meaning, they are more than just an article of clothing. The poleng, the ider-ider and the bebali cloths are required in ritual; and then there is also the appropriate ceremony attire one must wear. This has created a vibrant variety of textiles on the island, many of which have been preserved through the help of Threads of Life.

Traditionally, many of these cloths were handmade. Cotton would be collected, spun into yarn and coloured with natural dyes, then the women would weave in their homes. A village craft in its purest form. But even being in constant demand for rite and ritual, Bali’s population of weavers has waned over the decades.

Threads of Life, a fair trade business dedicated to sustaining the textile arts of Indonesia since 1998, have been part of the revival of weaving traditions across the island.

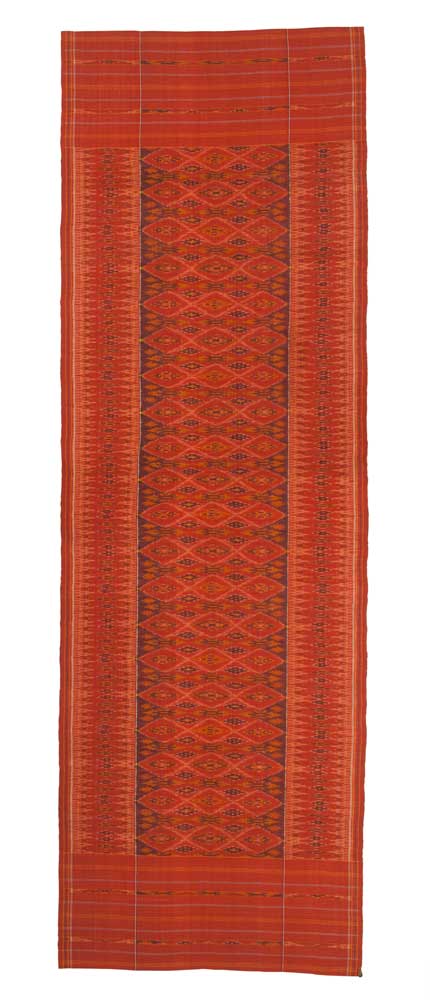

One example of this has been the revival of the the cepuk ritual cloth emblematic of Nusa Penida. Its standout, earthy red comes from the deep roots of the Morinda tree, which had been over-harvested to non-existence on the island. Threads of Life facilitated the replanting of 500 Morinda trees to ensure a future supply; but also had to introduce a natural red-dye recipe from Sumba to revive the ‘lost knowledge’ of the natural-dye process.

Time is indeed a tyrant: just in one generation the flame of knowledge can die out, hence why the embers must be constantly stoked.

There are many factors that draw people from their craft. When Bali’s tourism industry began to grow in the 80’s, many women exchanged their looms for labour: carrying rocks upon their head for infrastructure projects provided better financial assurance than their gorgeous tapestries. As did the hospitality industry. Slowly, with less and less people to weave this inherited knowledge into a physical form, evidence of its existence fades from the memories of not only the makers, but also its users.

Simpler textiles thus take their place for everyday use. They are affordable and may pass the benchmark, but are devoid of the soul its original predecessor possessed. No connection to the land nor to ancestry. Some generations know only this, robbed of a great inheritance.

There is hope of course. The fine, delicate cepuk of Nusa Penida is in high demand, and mainly from the local Balinese market. There is now prestige attached to wearing the traditional, natural-dyed cloth. As standards of living rise, so too does the need for class and quality in ceremonial attire. The same goes for the songket, the traditional ‘court cloths’ from Sidemen, Karangasem Regency. A growing local market has helped these crafts not just revive, but thrive. Weavers can remain at their looms if there is a market for their work; a promised income is by and large the most crucial factor.

Such cloths are aesthetic, fashionable and prestigious — what about a cloth that has none of these attributes? That is the current challenge for Threads of Life.

There is a category of uncut-warp bebabli (ritual) cloths used for specific ceremonies, like the rainbow prembon, the black-and-white atu-atu, and the white gedogan. These heirlooms have been widely abandoned, replaced by simple polyester. Though quite plain in pattern, their symbolism is profound. Woven with stripes and checks, these cloths are used for essential rites of passage, the lifecycle ceremonies like the 3-month baby ground-touching ceremonies (nyabutan), tooth-filings (metatah) andcremations (ngaben).

The colours of these cloths are stories on how one relates to the earth and elements, like eggs, stones and alang-alang grass; their stripes and chequered patterns symbolise boundaries, borders and balance. These storied symbolisms would be taught during the ceremonies, becoming an embodied knowledge. Those whose ceremonies did not use these age-old cloths never grew up with these subtle, symbolic lessons. What’s more, the original cloths would last decades, reused time-and-time again, simultaneously collecting and making memories.

When it comes to ‘revival’ of such a cloth, Threads of Life believes that there is power in cultural memory. That if reintroduced to the right communities, those nostalgic of a time where everything meant something, then demand for it will spread. There is a wordless appeal to them, something magical and emotional, something ‘taksu’ in the cloth that seems to live-on. Perhaps the bebali weavers will soon be busy again too.

Threads of Life

Instagram: @threadsoflifebali

Website: threadsoflife.com

This is three-part article on ‘Keeping the Craft Alive’, to read all three parts download our May-June Edition for free here, or go to:

• Part 1: The Stories on the Tapestries

• Part 2: Leaf Weaving in New Dimensions

• Part 3: New Canvases, New Opportunities